The Next Ten Years of Post-9/11 Security Efforts

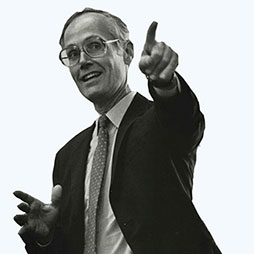

Ahead of the 9/11 Conference that NBR’s Slade Gorton International Policy Center will host on September 9, Senator Gorton reviewed the last decade of security policy and previewed the challenges to come.

Ten years after the attacks of September 11, 2001, the U.S. security infrastructure has changed dramatically. Sen. Slade Gorton, the first permanent appointment to the 9/11 Commission, tells NBR that much has improved. Intelligence-sharing and cooperation within the government have drastically increased. Meanwhile, the United States has fallen short of the commission’s recommendations for allocating intelligence funding and reforming congressional oversight.

Ahead of the 9/11 Conference that NBR’s Slade Gorton International Policy Center will host on September 9, Sen. Gorton reviewed the last decade of security policy and previewed the challenges to come.

What has the United States done well after 9/11 to improve its security efforts?

We are sharing intelligence far more effectively. Before 9/11 even the two divisions of the FBI couldn’t effectively share intelligence, much less could the CIA share with the FBI. Those walls, or stovepipes, were broken down—some of them before the 9/11 Commission even came into existence. In addition, the intelligence community was reformed by Congress as a result of 9/11 Commission recommendations and the creation of the National Counterterrorism Center together with the Directorate of National Intelligence (DNI) to preside over all intelligence activities in the federal government and serve as the chief adviser to the president.

That’s worked fairly well. It hasn’t worked as well as we think it could have, however, because our recommendation was that the DNI have budgetary authority over the other intelligence agencies, and Congress did not give the DNI that authority.

Nonetheless, our gathering, our sharing, and our use of counterterrorism intelligence have been greatly improved. They ought to be; we’re spending $80 billion a year now, double the amount that we were spending before 9/11. I think we’ve tripled the amount that we’re spending on the CIA, though much of that is for technical equipment and infrastructure. I think the number of people working for the CIA has only increased by about a third.

The United States has for the most part escaped domestic terrorism, but terrorists continue to produce violence overseas.

What we have done is to disrupt organizations like al Qaeda and all of its offshoots to the point that they can’t engage in the elaborate and effective planning for major incidents that they were able to do leading up to 9/11. What this has done is force them to go after their nearby enemies rather than their distant enemies. One of the real paradoxes in this whole struggle is that it really isn’t a struggle between civilizations; it’s a struggle within Islamic civilization. We haven’t begun to solve that problem, because in the ultimate analysis, we can’t solve it. That problem is only going to be solved inside that society itself.

In the emerging field of cybersecurity, both nonstate actors and state actors are thought to pose threats to the United States. Does this signal that we should move on past the last decade’s focus on counterterrorism?

I think “move on” would be the wrong description, because we can get awfully complacent when we’re successful against the kinds of threats that were represented by 9/11. The competence of anti-U.S. groups to engage in cyber threats and probably even in biological threats is lower than is that of some potential national enemies, but I believe that some of our national security people have said that a really serious cyberattack is the equivalent of declaring war.

While we have a considerable competition and even rivalry with China, that kind of attack from there seems highly unlikely. We’re more likely in those two threats to be dealing if not necessarily with Muslim extremism, with relatively small splinter groups with some kind of agenda, perhaps mostly an anarchist agenda. The way in which we’re defending ourselves against the 9/11 threats in the United States is clearly relevant to those small group attacks.

The 9/11 Conference will assemble a group from federal agencies, the 9/11 Commission, state government, and the private sector. What do you hope to discuss with this rare group?

It’s one of many conference that are taking place across the country in this manner, and that’s a good thing, because at least temporarily it will focus people’s attention on the fact that the threat is still out there. It’s changed a little bit in the course of the last ten years, but it’s still there. We’ll deal with questions of law enforcement, of privacy rights, and of civil rights in general, including how they have or have not been significantly affected by the way in which we seek out information today.

How successful have efforts to change the way in which we protect ourselves been, where are the gaps and shortcomings that still exist, and how will we deal with them? I hope we’ll deal with the rather stark contrast between our domestic successes and the very real, very expensive, and very fatal confrontations that we’re having outside the boundaries of the United States.

Not all the 9/11 Commission’s recommendations were put into force. What are the most important ways in which the United States has failed to turn the commission report into policy?

I would point to my own former institution, the Congress. We in the commission found that some 83 congressional committees had something to do with this subject. We thought there should be 4, as I remember, to concentrate that authority and oversight responsibility. Congress reduced the number from 83 to 79.

Now, how much does that affect our actual defensive performance? Maybe not that much. But with congressional authority that divided, oversight is ineffective. People in the administration can always find somebody on one of those committees to sympathize with them. It weakens Congress’s authority and influence in that field markedly. No one wants to give up his or her little corner on that authority, even though the institution would be so much better off if authority were concentrated.

This interview was conducted by Graham Webster, a former Intern of the National Bureau of Asian Research.