Japan’s Role in the Quad

Clarifying the Institutional Division of Labor in a Free and Open Indo-Pacific

This commentary is part of the roundtable “Quad Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific: Regional Security Challenges and Prospects for Greater Coordination.”

Japan has contributed to facilitating the evolution of the Quad—comprising Australia, India, Japan, and the United States—since its inception in 2004 when the grouping coordinated humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) operations in the wake of the Indian Ocean tsunami. This ad hoc, yet successful, collaboration propelled then Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe to institutionalize the Quad in 2007, with the help of the United States. Abe envisioned this “Quad 1.0” as a strategic grouping to facilitate Japan’s new strategic vision of an “arc of freedom and prosperity” that promoted liberal values across broader Asia.[1]

The four member states moved quickly to strengthen the grouping, holding an assistant secretary–level working group meeting at the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Regional Forum in May 2007. This led to the invitation of Japan, Australia, and Singapore to participate in the then bilateral Malabar naval exercise conducted by India and the United States. However, Chinese concerns and Japan’s strong emphasis on democracy and human rights made some members, particularly Australia and India, reluctant to consolidate the grouping. Abe’s sudden resignation in September 2008 further accelerated the collapse of Quad 1.0 in 2008.

When Abe became prime minister again in December 2012, he indicated his political desire to revitalize the Quad.[2] But this time Japan took a more cautious approach, and Abe did not immediately advocate for the grouping’s revival. In 2017, when the other Quad members began express similar concerns that the existing rules-based international order was being challenged by China, the group held a series of informal meetings that became known as “Quad 2.0.” Abe attempted to gradually consolidate this grouping by emphasizing not the threat of China’s rise but the importance of maintaining and enhancing the rules-based international order under the banner of the “free and open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP) concept.

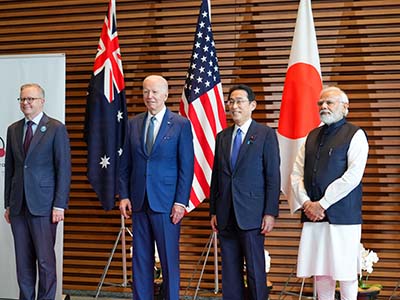

In 2021, further institutionalization (but notably not formalization) of the grouping, driven largely by China’s deteriorating relations with Australia and India, led to “Quad 3.0.” Today, the Quad no longer meets and coordinates on an ad hoc basis but instead has established a concrete agenda spanning issues such as global health, climate, critical and emerging technologies, cyber, space, infrastructure, and maritime security. The Biden administration has taken a leading role, while Japan under the Suga and Kishida administrations has actively supported these efforts and sought to enhance the existing rules-based international order by hosting the Quad Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in September 2021 and the Quad Summit in May 2022.

This commentary will consider how Japan has facilitated the revitalization and evolution of the Quad since 2017, situating it as an important strategic grouping to realize the FOIP.

Japan and the Role of Quad 3.0: Shaping Regional Order

While the United States is now leading the Quad, Japan has shown its consistent commitment to the grouping. Japan’s key objective remains the same—to effectively respond to challenges to the rules-based international order that the United States and its allies and partners have constructed since the end of the Cold War. In fact, this objective has become more prominent than ever following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. For Japan, Russia’s aggression toward Ukraine was a clear violation of state sovereignty and territorial integrity, which are the very basis of the existing international order. Even though the geographic scope of the Quad is the Indo-Pacific, given its primary objective as described above, diplomatic coordination among the four member states against Russia became imperative, despite India’s lukewarm response.

More fundamentally, the China factor has reshaped Japan’s FOIP vision, which was the backbone concept of the Quad 2.0. Japan has been concerned about China’s rapid development of military capabilities, including nuclear forces, without transparency. China’s continuing and increasing presence and advancement in the maritime domain, particularly in the East and South China Seas, are a significant challenge for not only Japan but also the existing international order, as illustrated by China’s rejection of the 2016 tribunal ruling in the arbitration case initiated by the Philippines. This challenge to the international order became more pronounced in light of China’s growing political and economic influence over Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and Africa through the Belt and Road Initiative, which challenged the international standard of development finance that Japan and other members of the Development Assistant Committee had long upheld.

By the mid-2010s, the existing regional mechanisms based on the U.S. “hub and spoke” alliance network and ASEAN-led institutions have not functioned as effectively as they did in the 1990s and 2000s. U.S. bilateral alliances in East Asia, including the U.S.-Japan alliance, were to check and balance the rising regional hegemon, while ASEAN-led institutions aimed to nurture regional norms and rules for stability through confidence-building measures. However, these mechanisms were essentially embedded in a unipolar system dominated by the United States. When such a system was disrupted by rising powers, particularly China, maintaining regional stability required new regional arrangements. This is well illustrated by the emergence of new U.S.-centered minilateral and multilateral frameworks—not only the Quad but also the AUKUS partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework.

In this context, the Quad becomes a strategically useful “nonmilitary” framework to garner regional support for maintaining and enhancing a rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida highlighted this need for regional participation in a March 2023 speech on the New Plan for Japan’s FOIP. He stressed the importance of understanding the diverse perspectives in the global South and the “means of sharing responsibility for global governance,” while also emphasizing that Japan would not “exclude anyone…create camps…[or]…impose values.”[5] Since regional states in the Indo-Pacific, particularly Southeast Asian states, have been concerned about the divisive force that great-power rivalry would set forth, the Quad can serve to neutralize such concerns.

This line of effort is made possible by the numerous minilateral efforts that have arisen in the Indo-Pacific. In the past, because the Quad was the only new regional framework, it sought to comprehensively counter international challenges ranging from defense to economic issues. However, the emergence of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework and the AUKUS defense partnership has allowed the Quad to focus more on political and nonmilitary areas of cooperation, such as global health and emerging and critical technology. As such, there is no immediate need to make the Quad a defense-oriented grouping; instead, its current agenda has opened a possibility for the Quad to cooperate with other states and institutions by providing regional public goods.

Additionally, the Quad’s inclusion of India as a core member is strategically important in supporting the rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific. While Japan has strengthened its bilateral and trilateral ties with the United States and Australia—through the Trilateral Strategic Dialogue in 2005, the 2015 Guidelines for Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation, and the 2022 Japan-Australia Reciprocal Access Agreement—Japan has also steadily developed economic and security relations with India since the early 2000s. The two countries have concluded several important agreements, including the Economic Partnership Agreement in 2011 and the Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement in 2020, while instituting the 2+2 Foreign and Defense Ministerial Meeting in 2019. These bilateral and trilateral efforts have laid a solid foundation for quadrilateral cooperation.

Admittedly, given India’s explicit and implicit emphasis on “strategic autonomy,” its diplomacy and strategic postures are not always aligned with the other three members. However, considering India’s desire to lead the global South, it is important for Japan and other members to have a mechanism to continuously engage with India.[5] Presently, India’s institutional engagement is not as strong as that of East Asian states, as it is neither a member of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) nor a signatory state of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. However, both the vision statement and the joint statement issued by the Quad Summit in May 2023 show that the Quad would work with other regional organizations led by the global South, such as ASEAN, the Pacific Islands Forum, and the Indian Ocean Rim Association. In this sense, the Quad becomes an important tool to bridge the gap with the global South and its institutions.

This does not mean that the Quad no longer has any potential to incorporate defense cooperation. On the contrary, it has gradually included tangible nontraditional security cooperation by establishing the Quad Partnership on Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief in the Indo-Pacific, the Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness, and the Maritime Security Working Group. Furthermore, quadrilateral defense cooperation continues through multilateral and bilateral military exercises, such as Malabar, in conjunction with the institutional development of the Quad.[6] However, it is quite rational to institutionally separate the Quad from traditional defense cooperation for the time being in order to prevent the countries in the global South from being excessively cautious about the framework. In the meantime, nontraditional security cooperation, particularly on HADR and through the Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness, should be extended to non-Quad countries to form broader Quad partnerships.

Clarifying the Institutional Division of Labor

The strategic posture that the Kishida administration has clarified for Japan has been helpful because it has the potential to further develop the Quad in this direction. However, there are questions about whether Japan’s strategic scope will become narrower, considering the release of the “three security documents” and “New Plan for a ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific.’”[7]

First, the three security documents lack Japan’s strategic vision in the Indo-Pacific. Understandably, the country’s acute focus is on Northeast Asia, where China, North Korea, and Russia surround Japan. As a result, Japan is buttressing its defense capabilities, including counterstrike capabilities. However, the documents contain no in-depth explanation of Japan’s strategic priorities toward other regions, such as Southeast Asia and South Asia, or regional frameworks, such as the Quad and ASEAN.[8]

Second, the “New Plan for a ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’” does not discuss how Japan would make the most of the existing regional institutions and frameworks for building a regional order, nor is there a strategic assessment of new regional institutions. For instance, the new plan mentioned ASEAN in the context of only functional cooperation, such as connectivity, food security, and global health. Given that regional frameworks are important diplomatic tools to shape rules and norms, this issue requires more careful attention.

A third question concerns the discontinuity between these new strategic documents and the previous FOIP-related and security-related documents. In particular, there is no statement regarding ASEAN centrality and unity in the Indo-Pacific, which Japan repeatedly emphasized in earlier documents. Without an explanation for such changes, these statements will cause misunderstanding and misperception. It will therefore be necessary for Japan to clarify what it expects from regional frameworks, including the Quad.

Clearly, Japan is currently more focused on managing power politics. Leaders and government officials, for example, repeatedly state that the country is facing “the most severe and complex security environment” in recent history.[9] Bilaterally and trilaterally, Japan has been strengthening security ties with its foremost ally, the United States, as well as important partners Australia and India. However, it is also imperative for Japan to strategize how it aims to nurture the global and regional order with like-minded states in the global South. The key to solving this problem is to clarify Japan’s vision for the institutional division of labor in the Indo-Pacific. In this context, the Quad has the potential to bridge a gap between the United States and its partners/allies and countries in the Global South. Furthermore, Japan should work to realize “rulemaking through dialogues” by facilitating linkages between the Quad and ASEAN in order to nurture regional rules and norms.

Kei Koga is Associate Professor and Head of Division in the Public Policy and Global Affairs Programme at the School of Social Sciences at Nanyang Technological University and a Nonresident Fellow at the National Bureau of Asian Research.

Endnotes

[1] Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan), Diplomatic Bluebook 2007 (Tokyo, March 2007), https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/other/bluebook/2007/html/h1/h1_01.html.

[2] Shinzo Abe, “Asia’s Democratic Security Diamond,” Project Syndicate, December 27, 2012, https://www.project-syndicate.org/magazine/a-strategic-alliance-for-japan-and-india-by-shinzo-abe.

[3] For example, see Prime Minister’s Office of Japan, “Policy Speech by Prime Minister KISHIDA Fumio to the 211th Session of the Diet,” January 23, 2023, https://japan.kantei.go.jp/101_kishida/statement/202301/_00012.html.

[4] Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan), “The Future of the Indo-Pacific: Japan’s New Plan for a ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific,’” March 20, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/100477791.pdf.

[5] For further discussion, see C. Raja Mohan, “India’s Return to the Global South,” Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore, ISAS Brief, January 16, 2023, https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/indias-return-to-the-global-south.

[6] For further discussion, see Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, “Malabar and More: Quad Militaries Conduct Exercises,” Diplomat, December 5, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/12/malabar-and-more-quad-militaries-conduct-exercises.

[7] Three security documents consist of the National Security Strategy, National Defense Strategy, and Defense Buildup Plan, which clarify Japan’s national security perspectives in the next five to ten years, while the “New Plan for a ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’” is the speech made by Prime Minister Kishida in March 2023 that discusses the principles and actions plans for realizing the FOIP vision.

[8] Kei Koga, “‘Kokka anzenhosho senryaku’ ni okeru ‘indo-taiheiyo’ chiikisenryaku e no kadai” [Lack of “Indo-Pacific” Regional Strategy in the New National Security Strategy], in “Nihon no Atrashi ‘Kokka anzenhosho senryaku’ to ni tsuite: bunseki to hyoka” [On Japan’s New “National Security Strategy” and Others: Analysis and Assessment], Research Institute for Peace and Security, December 12, 2022, 7–8.

[9] For example, see Prime Minister’s Office of Japan, “Policy Speech by Prime Minister KISHIDA Fumio to the 211th Session of the Diet”; Ministry of Defense (Japan), “Kokka boei senryaku: I. Sakutei no shushi” [National Defense Strategy: I. Intention)], December 16, 2022, https://www.mod.go.jp/j/policy/agenda/guideline/strategy/index.html; and Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan), Japan’s Security Policy (Tokyo, April 2023), https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/security/index.html.