India and the Quad

When a “Weak Link” Is Powerful

This commentary is part of the roundtable “Quad Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific: Regional Security Challenges and Prospects for Greater Coordination.”

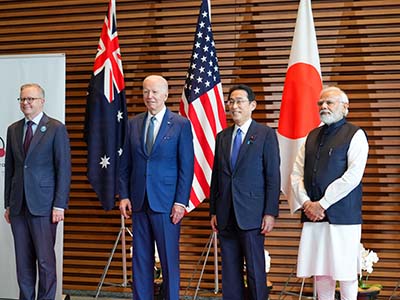

According to an aphorism coined by the Polish satirist Stanisław Jerzy Lec, “The weakest link in a chain is the strongest because it can break it.” This contrarian take on the well-known proverb “a chain is only as strong as its weakest link” presents a fresh way of understanding India’s role in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or Quad, between four Indo-Pacific democracies—the United States, Australia, India, and Japan.

That one of the Quad powers is “not like the others” has been a running theme in analysis since the grouping’s revival in November 2017, when senior diplomats from each country pledged to maintain “a free and open Indo-Pacific.”[1] India’s so-called “weak link” status stems both from perceptions of India’s material shortcomings and from gaps between external expectations and New Delhi’s policy choices.[2] Observers have raised questions about India’s capabilities and future ability to project power, refusal to embrace the Quad as an alliance formation, unwillingness to frame the grouping as a counterweight to China, and retention of a parallel, strategic relationship with Russia.[3]

In geography and in name, however, the idea of the free and open Indo-Pacific includes and elevates India. A crucial swing state in this strategic theater, India is imagined as an indispensable material, economic, and normative partner. A clear appetite on the part of the other Quad members to keep relations with India productive and on a forward trajectory grants the “weak link” an outsized capacity to set the pace and direction of the grouping. For India, strategic relationships with Quad partners are attractive because they support the country in building out key capabilities and contending with its “China challenge.” However, New Delhi’s locally situated perspectives on how to address regional security challenges and on preferred futures for global order are what will shape the scope of India’s engagement with the Quad and choice of partners outside the grouping. Ultimately, if some members see the free and open Indo-Pacific construct as a blueprint for diplomatic, economic, and military convergence,[4] India is clearly shaping the terms and the limits of this convergence.

India’s Particular Indo-Pacific Challenges

The vision that currently animates key Indian political actors and officials is the ambition for India to emerge as a “leading power”—an independent pole in a multipolar world.[5] Even if this is “a goal on the horizon” rather than a “statement of arrival,” according to External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar,[6] India can be an independent pole only when it is materially strong enough, and only in a global order that is multipolar.

The urgency of material resourcing. The importance to India of relations with the United States centers—owing to U.S. economic and technological supremacy—on the U.S. capacity to aid India in the building out of its economic and military national power. For Jaishankar, “the most impressive [Asian] growth stories of the last 150 years have all been with the participation of the West.”[7] For this reason, “India has to maintain a narrative in the United States of its value, whether it is in terms of geopolitics, shared challenges, market attractions, technology strengths or burden-sharing.”[8]

The United States identifies the Quad as central to its Indo-Pacific strategy, and the Quad construct attributes to all four members the status of being pivotal powers in the Indo-Pacific. It is, therefore, unsurprising that India has found it expedient to partner with this grouping. Existing and developing bilateral and trilateral modes of economic and defense cooperation between India and the other three Quad partners bolster its “networking power” and point to further growth opportunities.[9] India’s relations with Japan have grown since the turn of the millennium. Since 2005, India has emerged as the largest recipient of Japanese official development assistance.[10] The two countries have signed multiple agreements centered on security and defense since 2008, upgrading their 2+2 dialogue to the ministerial level in 2018. They conduct regular bilateral military exercises on land, in the air, and at sea.[11] More recently, India has also boosted ties with Australia as their respective relationships with China have taken a sharp, downward turn.[12] In 2020, the two countries committed to a comprehensive strategic partnership, and India approved the expansion of the U.S.-India-Japan Malabar naval exercise to include Australia. New Delhi and Canberra also signed an economic cooperation and trade agreement in 2022, raising hopes for an upturn in bilateral trade.[13]

India has, however, frequently confronted limits to its defense and economic cooperation with the United States. Between 2002 and 2020, it signed the four key enabling defense agreements that the United States signs with all defense partners, and in 2016 the United States recognized India as a “major defense partner.” Yet to some in India’s strategic community, the United States appears only weakly committed to advanced technology cooperation.[14] Despite the launch in 2012 of the flagship U.S.-India Defense Technology and Trade Initiative, which intended to galvanize bilateral cooperation on defense development and production, perceptions circulate of persistent foot dragging among the key U.S. actors and bodies that oversee technology restrictions and export controls.[15] The threat to India of sanctions under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act for purchasing Russia’s S-400 surface-to-air missile system raised additional doubts about a “ceiling” for defense cooperation.

Russia, by contrast, consolidated defense ties with India throughout the Cold War and has pursued a formal, long-term military-technical cooperation partnership with it since 2011.[16] India is likely to remain dependent on Russia for years into the future for several critical technologies, including fighter aircraft, cruise missiles, and submarines.[17] Despite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, New Delhi and Moscow have strengthened their relationship in many ways. The two partners held their first 2+2 dialogue in 2022 and are currently negotiating a free trade deal. Meanwhile, India’s purchases of Russian oil have increased, and India has agreed to adopt the Russian financial messaging system, the Financial Messaging System of the Bank of Russia, to make bank payments to Russia.[18]

India’s high-level defense cooperation with Russia sets it apart from the other three Quad countries. India’s Russian-origin weapons systems pose challenges to Quad interoperability, while the United States’ alliance partnerships with Japan and Australia permit deeper levels of advanced technological exchange among these three countries. Russian intelligence-collection platforms, also pose a security risk for their capacity to collect information on advanced U.S. technology.[19] Commenting on these interoperability barriers, one career U.S. naval officer has argued—in a personal capacity—that “an honest evaluation of the Quad militarily will highlight the fact that India is hampering its overall effectiveness. What’s interesting is that this is by choice.”[20]

Distinctive security priorities. The United States has preexisting security alliances with Japan and Australia. All three countries are working to balance China’s power projection in the East and South China Seas by economic, diplomatic, and—if necessary—military means. India has been unwilling to pursue an overt collective strategy of Chinese containment, or to frame or enact the Quad as a militarized collective. This stance stems from Indian misapprehensions about a punitive response from Beijing if New Delhi is seen to be actively and explicitly supporting U.S.-led containment efforts. For India, a war with China is simply not an option.

Since the border clashes between Chinese and Indian troops in the Galwan Valley in mid-2020, however, New Delhi’s appetite for strategic partnerships has grown, and its caution over strategic cooperation, with the United States in particular, has diminished. India’s circumspect engagement with the Quad has also abated, rising to participation in summit-level meetings from March 2021. Nonetheless, in a briefing after the first (virtual) Quad Summit, Foreign Secretary Harsh Vardhan Shringla dismissed questions about the function of the grouping as a mechanism to contain China: “We have always said that the Quad does not stand against something…it stands for something which is positive…. So that I think should put to rest any speculation about [the] Quad’s activities directed against any States or others.”[22]

Indian strategic elites remain resistant to a deeper institutionalization of the Quad along hard security lines.[23] For example, India has formally delinked the expanded U.S.-India-Japan Malabar naval exercise from the Quad, and it has not joined the United States in enforcing freedom of navigation via patrols in the South China Sea. The Quad does still operate as a vehicle for security provision—widely cast—through an emphasis on capacity building and regional public goods: health, climate, critical and emerging technology, maritime cooperation, infrastructure, cyber, and space. The addition of maritime domain awareness (MDA) activities to the grouping’s schedule of activity in May 2022 has been described by one observer as an “explicitly anti-China step.”[24] Yet the Indian description of the move did not explicitly frame it as such, describing the initiative as “enhancing regional MDA of select countries in the region to combat illegal and unreported fishing; and to augment their capacity to address humanitarian and natural disasters by providing technology and training.” India clearly does not see value in openly targeting China via the Quad, even if it is incrementally accepting a more expansive security for the grouping. China also matters for the success of multilateral initiatives that are important to India: for example, in the runup to the G-20 Summit, New Delhi did not participate in the July 2023 Talisman Sabre military exercise between the United States and Australia, apparently to avoid displeasing Beijing.[25]

Resistance to the role of “socialisée” in the free and open Indo-Pacific. In terms of values, too, Indian leaders—in both discourse and policy—understand distinctively several aspects of the apparently shared Quad objectives of “freedom and openness.” India’s caveated embrace of the liberal international order has appealed to a broadly conceived liberal community of states, delivering recognition, status, and material dividends. But as for many states who are not its central authors, the liberal international order has functioned more as a normative and material resource than an article of faith, with elements selected and rejected as required.

India’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has signaled divergence between Washington and New Delhi on fundamental issues of global order. India has repeatedly declared that it seeks to promote a democratic and rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific and that it will work with the Quad to keep seas, space, and airways free and open. Yet the convergence of India’s interests with the United States or U.S.-allied partners in the Indo-Pacific does not equate to India’s wholesale embrace of a U.S. vision of order. India’s insistence on a plural and inclusive conception of the Indo-Pacific, eschewal of the Quad as a formalized alliance, and dismissal of outside assessments of or commentary on India’s internal functioning as a democracy are evidence of this. The current Indian leadership’s aspiration for a multipolar order logically implies an end to U.S. global hegemony as well as Chinese regional hegemony.

Keen to maintain its strategic autonomy and imprint its own identity in the region, India will continue to engage selectively with the liberal international order rather than take on the role of “liberal socialisée”—that is, of a state that is straightforwardly socialized into embracing and upholding a liberal order—in the shadow of the United States and its allies.[26] India also does not share the imperative to tackle China explicitly as a systemic competitor of the United States. Instead, as one observer argued in January 2023, “the [Indian] government’s strategy is to bring China around to accept India as an independent pole, even if it is [in] a China-influenced world order.”[27] There is no “natural” imperative for India to identify with U.S. visions of order in the Indo-Pacific.

The Strength of India’s “Weak Link” Status

At the March 2023 Raisina Dialogue, India’s flagship annual conference on geopolitics, Jaishankar was asked whether official Indian rhetoric about the Quad as not being directed “against” anyone was apologetic. He replied, “What I would not like to be defined as is standing against something or somebody, because that diminishes me. That makes it out as though some other people are the centre of the world and I’m only there to be for them or against them.” Lightheartedly, he added, “I think I’m the centre of the world, but that’s a different matter.”[28]

The longer-term ambition for India to emerge as a “leading power” or an independent pole in world politics makes conflicting demands of its relationship with the Quad. India needs deep strategic relationships with Quad partners to meet its resourcing imperatives, but it does not seek to prop up a regional order that serves any of the other three partners before India or that imposes socializing pressures that diminish its status and options. The contemporary value of the Quad for India is as a steppingstone to greater power and status and the realization of a multipolar order. Three key factors—the need for unconstrained material resourcing, the avoidance of the provocation of China, and resistance to a role as a socialisée in a U.S.-led order—are the imperatives behind India’s clear determination to approach the Quad on its own terms.

Looking ahead, New Delhi will very likely continue to seek high-technology cooperation from partners both within and outside the Quad. India’s preferences for collective security provision will continue to center on regional capacity building and public goods. Given the high costs of appearing to participate explicitly in collective, U.S.-led efforts to contain China, New Delhi will likely continue to resist a deeper institutionalization of the Quad along hard security lines. The current U.S. strategy of allowing the Quad to develop “organically” rather than pushing for an alliance-like formation in Asia is not only compatible with Indian preferences but is in several ways a product of them.[29] This is the strength of India’s “weak link” status in the Quad.

Kate Sullivan de Estrada is Director of the Contemporary South Asian Studies Programme and Associate Professor in the International Relations of South Asia at the Oxford School of Global and Area Studies and a Fellow of St Antony’s College at the University of Oxford.

Endnotes

[1] Rahul Roy-Chaudhury and Kate Sullivan de Estrada, “India, the Indo-Pacific and the Quad,” Survival 60, no. 3 (2018): 181–94.

[2] Aditi Malhotra, “Engagement, Not Entanglement: India’s Relationship with the Quad,” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, May 1, 2023, https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2023/05/01/engagement-not-entanglement-indias-relationship-with-the-quad.

[3] Amy Kazmin and Demetri Sevastopulo, “India’s Covid Calamity Exposes Weakest Link in U.S.-Led ‘Quad’ Alliance,” Financial Times, June 15, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/8c5e6c26-6583-4524-994d-2f52b37d9216; Sameer Lalwani, “Reluctant Link? India, the Quad, and the Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” in “Mind the Gap: National Views of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” ed. Sharon Stirling, German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2019, 27; Derek Grossman, “India Is the Weakest Link in the Quad,” Foreign Policy, July 23, 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/07/23/india-is-the-weakest-link-in-the-quad; and Chet Lee, “India: The Quad’s Weakest Link,” Diplomat, October 19, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/10/india-the-quads-weakest-link.

[1] Lalwani, “Reluctant Link?” 34.

[1] Ashley J. Tellis, “India as a Leading Power,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 4, 2016, https://carnegieendowment.org/2016/04/04/india-as-leading-power-pub-63185; and Happymon Jacob, “The ‘India Pole’ in International Politics,” Hindu, November 23, 2022, https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/the-india-pole-in-international-politics/article66170757.ece.

[6] S. Jaishankar, “Beyond the Delhi Dogma: Indian Foreign Policy in a Changing World” (Ramnath Goenka Lecture, New Delhi, November 14, 2019), https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/32038.

[7] S. Jaishankar, The India Way: Strategies for an Uncertain World (New Delhi: Harper Collins, 2020), 123.

[8] Jaishankar, The India Way, 126.

[1] Sumitha Narayanan Kutty, “India, Japan, and the Quad: Furthering an ‘Indispensable’ Partnership,” Center for the Advanced Study of India, India in Transition, June 5, 223, https://casi.sas.upenn.edu/iit/sumithanarayanankutty.

[10] Akash Sahu, “India-Japan Economic Ties Key to Regional Stability,” East Asia Forum, April, 28, 2022, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2022/04/28/india-japan-economic-ties-key-to-regional-stability.

[11] Purnendra Jain, “Shared Anxieties Drive India-Japan Defence Ties Upgrade,” East Asia Forum, December 12, 2019, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2019/12/12/shared-anxieties-drive-india-japan-defence-ties-upgrade.

[12] Priya Chacko, “India-Australia Relations: Neglected No More,” Center for the Advanced Study of India, India in Transition, June 19, 2023, https://casi.sas.upenn.edu/iit/priyachacko.

[13] Biswajit Dhar, “ECTA Expected to Boost Australia-India Bilateral Trade,” East Asia Forum, June 1, 2023, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2023/06/01/ecta-expected-to-boost-australia-india-bilateral-trade.

[14] Sameer Lalwani et al., “Toward a Mature Defense Partnership: Insights from a U.S.-India Strategic Dialogue,” Stimson, Report, November 16, 2021, https://www.stimson.org/2021/toward-a-mature-defense-partnership-insights-from-a-u-s-india-strategic-dialogue.

[15] Lalwani et al., “Toward a Mature Defense Partnership.”

[16] Erin Mello, “The Enduring Russian Impediment to U.S.-Indian Relations,” War on the Rocks, February 13, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/02/the-enduring-russian-impediment-to-u-s-indian-relations.

[17] Sameer Lalwani and Happymon Jacob, “Will India Ditch Russia? Debating the Future of an Old Friendship,” Foreign Affairs, January 24, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/india/will-india-ditch-russia; and Mello, “The Enduring Russian Impediment to U.S.-Indian Relations.”

[18] Mello, “The Enduring Russian Impediment to U.S.-Indian Relations.”

[19] Mello, “The Enduring Russian Impediment to U.S.-Indian Relations.”

[20] Lee, “India: The Quad’s Weakest Link.”

[21] Arzan Tarapore, “Zone Balancing: India and the Quad’s New Strategic Logic,” International Affairs 99, no. 1 (2023): 239–57.

[22] Harsh Vardhan Shringla, “Transcript of Special Briefing on First Quadrilateral Leaders Virtual Summit by Foreign Secretary,” Ministry of External Affairs (India), March 12, 2021, https://www.mea.gov.in/virtual-meetings-detail.htm?33656.

[23] Patrick Gerard Buchan and Benjamin Rimland, “Defining the Diamond: The Past, Present, and Future of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, CSIS Brief, March 2020, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/200312_BuchanRimland_QuadReport_v2%5B6%5D.pdf.

[24] Ramon Pacheco Pardo, cited in Zaheena Rasheed, “Quad Launches ‘Anti-China’ Maritime Surveillance Plan,” Al Jazeera, May 28, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/5/28/why-has-the-quad-launched-an-anti-china-surveillance-plan.

[25] Nayanima Basu, “Why India Did Not Participate in Australia’s ‘Talisman Sabre’ Military Exercise,” ABP Live, August 3, 2023, https://news.abplive.com/india-at-2047/why-india-did-not-participate-in-australia-s-talisman-sabre-military-exercise-abp-live-english-news-1620208.

[26] Kate Sullivan de Estrada, “India and Order Transition in the Indo-Pacific: Resisting the Quad as a ‘Security Community,’” Pacific Review 36, no. 2 (2023): 378–405.

[27] Ali Ahmed, “Under Modi, India’s China Strategy Has Gone From Strategic Proactivism to Docility,” January 13, 2023, Wire, https://thewire.in/security/modi-india-china-strategy-docility.

[28] “Secretary Antony J. Blinken and Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong, and Japanese Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi at the Raisina Dialogue: Quad Foreign Ministers’ Panel,” U.S. Department of State, March 3, 2023, https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-and-indian-external-affairs-minister-subrahmanyam-jaishankar-australian-foreign-minister-penny-wong-and-japanese-foreign-minister-yoshimasa-hayashi-at-the-raisina-dialo.

[29] Joshua T. White, “After the Foundational Agreements: An Agenda for U.S.-India Defense and Security Cooperation,” Brookings Institution, January 2021.