Commentary

Foreign Policymaking in South Korea

NBR visiting fellow Jeonghee Lee recommends that careful consideration be paid to the differences between the U.S. and South Korean democratic systems in order to achieve a lasting convergence of the two allies’ visions for the Indo-Pacific and their own domestic growth.

As a key U.S. ally in the Indo-Pacific, South Korea is often thought of as having a similar democratic composition to the United States. While both countries’ democratic structures are governed by the same political spheres—the executive office, the legislative branch, the bureaucracy/civil service, the judiciary, and civil society—each sphere exercises a varying level of agency within the foreign policymaking process. The United States operates under a framework that is closer to ideal democratic constitutionalism, where the power to influence foreign policy is more equally distributed among all five political spheres. In contrast, the South Korean democratic structure has concentrated power in the executive and bureaucratic spheres, allowing them to dictate the foreign policymaking process.

Failure to recognize the asymmetrical power dynamic in policymaking severely undercuts the effectiveness of South Korean foreign policy and its ability to align global and regional efforts with allies like the United States. Likewise, from the perspective of the United States, recognition of the structural and procedural differences in foreign policymaking has the potential to enhance the effectiveness of political engagement. Thus, the interrelationships among South Korea’s political spheres and the influence they exercise is strategically important for the success of the allies’ strategies for the Indo-Pacific region.

KOREAN FOREIGN POLICYMAKING: A FRAMEWORK IN TRANSITION

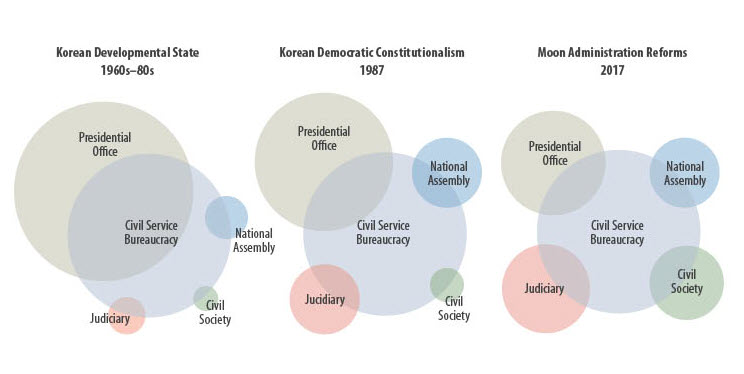

Comparing democratic frameworks, South Korea appears to be a weaker democracy vis-à-vis the United States because of the imbalance among its five political spheres. The compounded influence of the executive and bureaucratic spheres began in the 1960s and continued into the 1980s, when underdeveloped legislative, judicial, and civil society spheres allowed power to be accumulated in the presidency and bureaucracy. Change occurred in 1987 with the new constitution replacing the authoritarian regime, which strengthened the independence of the National Assembly and judiciary and enabled South Korea’s shift to a slightly more balanced bureaucratic statehood. Although appearing to introduce a balance of power closer to that of the United States, the presence of the legislative and judicial spheres did little to redistribute power in South Korea away from the presidency and bureaucracy. While maintaining the appearance of a decentralized government, the system of checks and balances still occurred largely between the executive and bureaucratic spheres.

Under reform efforts initiated by the Moon Jae-in administration in 2017, South Korea experienced abrupt development in its civil society sphere. However, the current level of soft infrastructure and lack of support prevents civil society from decoupling from partisan thinking, with most civic organizations and think tanks remaining government-affiliated. Consequently, civil society remains closely tied to the direction provided by the executive and bureaucratic spheres. To realize a mature and stable democracy, South Korea needs to nurture and support communities and civil society. It needs to institutionalize legal and administrative frameworks to devolve political and administrative power from political elites and bureaucrats to civil society by opening the door to the political and policy processes. Despite hopeful progress by the emerging legislative, judicial, and civil society influencers in South Korea’s democratic framework, power over foreign policymaking has remained firmly centralized in the presidency and bureaucracy.

POLITICIZATION OF SOUTH KOREAN BUREAUCRACY

The relationships between South Korea’s political spheres contributed to the politicization of the bureaucracy. Up until 2002, the government structure displayed a two-level system led by a strong, charismatic presidential office and complemented by a workforce of civil service bureaucrats. With the conclusion of Kim Dae-jung’s presidency in 2003, leadership shifted to become more democratically oriented. Under the following Roh Moo-hyun administration, an additional layer of bureaucracy was added between the democratic leadership and the civil service with the creation of the senior executive service.

In this orientation, the three bureaucratic levels—political appointees, senior executive service, and civil service—have become polarized between worldviews focused on self-reliance and interdependence. The views of political appointees skew toward self-reliance, affording general support for progressive policies and pro-China sentiment. Meanwhile, members of the civil service tend to support international engagement, exhibiting pro-U.S. sentiment and fostering general approval of conservative policies. The senior executive service bridges the two polarized ends of the spectrum. Members of the service are of different worldviews, split between the majority Administrative Leadership Alliance, promoting civil service ideals, and the minority self-reliance faction, supportive of political appointees. The political views of the three levels carry over into the composition of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, folding residual political ideology into the South Korean foreign policymaking process. The divisions forged between the political appointees, the senior executive service, and the civil service create three defined levels for engaging the South Korean bureaucracy to influence the foreign policymaking process.

LIMITATION ON EXECUTIVE POWER

An important consideration is the cycle of the president’s and executive office’s dominance. Constitutional constraints limiting the number of terms to one and the length to five years have created pronounced stages for South Korean presidential administrations. There is a significant fallout for foreign policymaking after the third year because the final two years of a term are devoted to finding and promoting a successor for the administration in power. This cycle provides a short window where changes to foreign policy may be considered by the executive office.

Equally important is acknowledging the strong divide in public opinion over certain policies adopted at the executive level, but rejected at the level of civil society. During the current Moon administration, civil society has been most concerned over economic policy issues. The changes of economic and labor market policies advocated by the executive level were met with disapproval by 62% of the public, according to Yonhap News, and caused a sharp decline in Moon’s popularity rating. As civil society’s role in South Korea’s democratic framework continues to expand, public opinion may carry more influence in foreign policymaking within the productive three-year period.

CONCLUSION

With the United States attempting to mobilize support for its Indo-Pacific strategy, successful implementation of this strategy will depend on how U.S. leaders choose to strategically engage with the institutions that shape South Korea’s foreign policymaking, ranging from the executive office to civil society. The United States should focus on the first half of a presidential term, when the incoming president and staff form the new administration’s policy goals. At the same time, the United States would be well-advised to strategically approach actors and decision-makers on different levels within the South Korean bureaucracy and with different worldviews. Careful consideration must also be paid to the differences between the U.S. and South Korean democratic systems in order to achieve a lasting convergence of the two allies’ visions for the Indo-Pacific and their own domestic growth.

Jeonghee Lee is an Associate Professor in the Department of Public Administration at the University of Seoul and was a Visiting Fellow in NBR’s Washington, D.C., office.

This commentary was edited by Emily Laur, an intern with NBR’s Energy and Environmental Affairs group.