Interview

Chinese Engagement in Latin America and the Impact on U.S.-China Competition

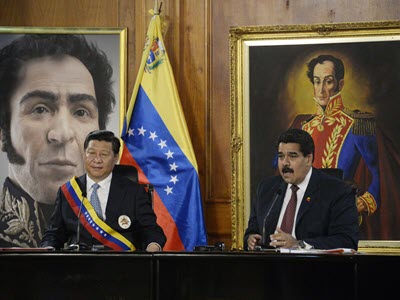

China’s growing levels of economic statecraft in Latin America come with the potential for greater geopolitical influence that could threaten U.S. interests in the region. Rachel Bernstein interviewed Pepe Zhang from the Atlantic Council to better understand the nuances in the China–Latin America relationship and the implications for Sino-U.S. strategic competition. Focusing on Venezuela as a case study, this Q&A examines whether Chinese investments could heighten China’s geopolitical influence in the Western Hemisphere.

How would you characterize China’s engagement in Latin America? What are the factors driving bilateral relations with Venezuela?

Prior to the 2000s, there was limited commercial, economic, or diplomatic engagement between China and Latin America. This changed when China significantly scaled up its global search for resources in the early 2000s, many of which are located in Latin America, such as Chilean and Peruvian copper, Venezuelan oil, and Brazilian soybeans and iron ore. Simultaneously, Latin America was experiencing a “pink tide” with leftist leaders being elected throughout the region. China, as a result, was able to conduct high-level diplomatic exchanges with several Latin American governments. Both the political relationships and the highly complementary commercial relationships took off. Between 2000 and 2019, the bilateral trade volume increased from $12 billion to $300 billion.

It is within this context that China’s relationship with Venezuela began to grow. Under the Hugo Chávez regime, China and Venezuela established a mutually beneficial commercial exchange. China was, at the time, the second-largest importer of oil globally (now it is the largest), and Venezuela had (and still has) the world’s largest proven oil reserve. In terms of the current relationship, I think we are at an especially critical moment, given where oil markets are these days. There has been a significant drop in demand for oil caused by Covid-19. On the supply side, despite the recent OPEC+ agreement on production cuts, the global supply glut will continue for the foreseeable future. Oil exporters will likely see a significant reduction in export revenues, possibly leading to deteriorating fiscal positions affecting their ability to finance or repay projects and obligations. This could affect relations between China and Venezuela, as their relationship has very much hinged on oil and oil-backed financing.

Has Venezuela’s economic collapse influenced Chinese investment decisions in the greater Latin America region?

Given its production and export collapse, Venezuela is having trouble fully repaying Chinese loans in cash terms. The case of Venezuela provides important lessons for Chinese investors who are relatively new to the region, prompting them—state-owned enterprises and policy banks as well as private-sector investors—to become more cautious and sophisticated in their dealings overseas. Some experts argue that the drivers of China’s engagements in Venezuela were primarily political and geopolitical, with commercial interests playing a relatively secondary role. Increasingly, however, the Chinese companies and the banks themselves are realizing that they need to be much more cognizant of the financial and economic feasibility of projects. These lessons apply not just to properly assessing risks at the project level, but also at the macro and country levels.

However, Chinese investors’ growing sophistication does not solely stem from their experiences abroad. On the domestic side, China is undertaking an ambitious economic rebalancing toward a more sustainable growth model. The government is making a significant push for companies to make responsible investment decisions. As domestic credit conditions start to tighten, as they should, not all companies are given the same level of access to the type of easy and affordable credit that they grew accustomed to. In this context, many Chinese investors are re-evaluating their actions and strategies abroad. At the end of the day, sound investment decisions should be driven by a real need to internationalize and diversify portfolios through projects and opportunities unavailable domestically—and those projects should make financial sense, or at the very least represent a tolerable risk.

In the case of Venezuela, loans from policy banks still account for the lion’s share of Chinese financing to the country. Similar patterns also apply to a few other countries in the region, but generally we see this trend tapering in both absolute and relative terms.

In absolute terms, we have seen an overall reduction in official Chinese lending to Latin America. Lending peaked around four to five years ago, and since then the numbers have been plateauing or decreasing. Venezuela plays a part in these numbers.

In relative terms, companies and private-sector investments have grown in relation to official lending, changing the composition of Chinese financing flows to Latin America. For context, overall FDI inflow has been on the decline during four out of the past five years in Latin America. China, however, appears to be one of the few outliers in this calculation. This is partially attributable to the fact that Chinese private-sector investors have been more active in the region.

Is Venezuela important to China’s long-term geostrategic ambitions in Latin America? How do relations between the two countries affect U.S. strategic interests?

Venezuela is strategically important to China’s long-term commercial and geostrategic ambitions in Latin America. In terms of official lending, over the past fifteen years China has loaned Venezuela roughly $60 billion. This accounts for more than 40% of official Chinese lending to the Latin American and Caribbean region. To put this in perspective, Venezuela only accounts for about 3%–4% of regional GDP, which indicates the country’s outsized strategic importance for China.

Venezuela is also strategically important for the United States and at one time was among its most important allies in Latin America. The United States had been the largest oil importer and consumer in the world, but the shale revolution has reduced its reliance on Venezuela and other oil exporters. Nonetheless, there still is considerable commercial complementarity between the two economies. As for geopolitics, the current official U.S. government position toward Venezuela is that it is a source of regional instability, affecting U.S. interests in Latin America.

While Venezuela may not be the primary foreign policy priority for either China or the United States, it is certainly part of each country’s calculus and therefore plays into the competitive dynamics. China sees increased pushback from the United States around the world against the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Chinese-led 5G efforts, including in Latin America. The United States perceives an increasingly assertive China around the globe—in the South China Sea, in Europe, in Africa, and now in Latin America. While U.S.-China relations globally and in Latin America are not and should be not a zero-sum game, in recent years we have seen more and more actions on both sides feeding into this narrative of a global chessboard of U.S.-China rivalry. It has almost become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In 2018, China backed the Maduro regime, going against many Latin American and Western countries. Why would China do this, and has its support for Nicolás Maduro wavered in the last year?

Since Maduro came to power, China has not offered any new credit lines to Venezuela and only renewed some of the preexisting credit lines. While Venezuela remains strategically important to China, the fact that China has reduced its financial support in recent years indicates that there is conscious and cautious thinking behind the current state of play in bilateral relations.

Many regional governments and Western countries, including the United States, have supported Juan Guaidó. On the other side, Turkey, Iran, Russia, China, and others are supporters of the Maduro regime. Compared to most members of the Maduro camp, China takes a more pragmatic approach to foreign policy and international commerce in general. In Venezuela, Chinese involvement also seems less driven by political or ideological ambitions. It has more commercial interests at stake there than most other countries supporting the Maduro regime do.

In terms of what could happen going forward, China will likely need a more compelling argument for why it should switch recognition to Guaidó. Specifically, he will have to make the case that Venezuela’s debts will only be repaid and its economy will only recover if there is a regime change. He also must convince Chinese leaders that regime change is not only inevitable, but that the failure to move in this direction will make Venezuela a liability and reputational risk for China.

How do Chinese investments in Latin America, such as through BRI, factor into the U.S.-China competition for global influence?

Initially, BRI was focused on improving physical infrastructure in Central Asia, but it is now global in scope. In 2017 the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs officially announced that Latin America is a natural extension of the initiative, and in the same year Panama became the first Latin American country to join BRI. There are currently nineteen Latin American and Caribbean countries signed onto it.

The United States has pushed back very vocally against some of the BRI projects both in Latin America and globally. The U.S. State Department and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo have released high-level statements opposing BRI in the region. On more than one occasion, Secretary Pompeo has advised Latin American countries to exercise increased caution with Chinese projects, citing concerns over debt, sustainability, and environmental compliance, among other issues.

Analyzing Chinese investment in Latin America solely through the lens of BRI, however, would be incomplete. BRI still operates predominantly through official lending and state-owned enterprises; yet increasingly we see Chinese private-sector investment in the region. This investment is not branded or officially recognized as part of the initiative. In Brazil, one of the countries where Chinese investment is most pronounced, there is significant Chinese private-sector investment in the technology sector. For example, DiDi, the Chinese rideshare app, invested in its Brazilian counterpart 99Taxis. Ant Financial (Alibaba) and Tencent have likewise invested in local Brazilian credit card/payment apps Nubank and StoneCo. Of note, many major U.S. private investors such as Sequoia Capital and Berkshire Hathaway have also invested in these same Brazilian apps.

There is thus considerable Chinese investment entering Brazil and other Latin American countries that is not necessarily tied to the Chinese government. However, in today’s hypercompetitive, zero-sum geopolitical context, these investment deals could be a factor in U.S.-China competition for global influence.

Several of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies are Latin American or Caribbean nations. How does this influence China’s behavior in the region?

Many countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have approached diplomatic recognition with China or Taiwan from an economic standpoint by examining which relationship can provide greater economic benefits. Everything else being equal, when faced with a choice between Taiwan and China, a few regional policymakers have acknowledged in private that the economic analysis is straightforward. Indeed, China has been generous in rewarding its new allies, while Taiwan continues to double down on economic assistance to its own allies in hopes of safeguarding these relations. However, changes in diplomatic recognition in Latin America and the Caribbean are arguably also a reflection of changes in cross-strait relations rather than only due to China’s behavior in the region. During the Ma Ying-jeou leadership from 2008 to 2016, cross-strait relations were friendlier and Beijing was less active internationally in courting Taiwan’s diplomatic allies. As cross-strait relations have grown frostier under Tsai Ing-wen, both sides have been more aggressive in maintaining or developing new diplomatic relations.

Pepe Zhang is an Associate Director at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.

This interview was conducted by Rachel Bernstein, a Project Associate with the Political and Security Affairs group at NBR.