Building Renewable Energy in Bangladesh

Clean EDGE Asia Fellow Shafiqul Alam provides an overview of the renewable energy potential in Bangladesh, outlines the economic and energy security benefits of renewable energy, and identifies renewable energy measures that could be implemented. He also identifies financing mechanisms to foster renewable energy development as well as the necessary stepping stones to create an enabling ecosystem for scaling up renewable energy.

During the last decade, Bangladesh has made great strides toward accelerating power-generation capacity to ensure 100% access to electricity. The country officially announced universal access to electricity in 2022, yet it faces uphill challenges, including overcapacity, increasing reliance on imported fossil fuels, rising electricity costs, and load shedding.[1] Although renewable energies such as solar and wind are highly competitive compared to fossil fuels, the country’s success with renewable energy is limited. The price volatility of fossil fuels, driven by the Ukraine crisis, manifests that renewable energy is the pathway that Bangladesh must choose to reduce its reliance on imported liquefied natural gas (LNG) and other fossil fuels. There is, however, an information asymmetry over the potential of renewable energy as well as financing instruments and applicable interest rates for loans.

Building on previous studies, this essay lays out a brief overview of the renewable energy potential in Bangladesh and outlines the economic and energy security benefits of renewable energy. Reviewing published documents and based on discussions with sectoral experts, it then identifies challenges in the sector and the renewable energy measures that could be implemented without disrupting agricultural production. This essay, furthermore, touches on financing mechanisms to foster renewable energy development as well as the necessary stepping stones to create an enabling ecosystem for scaling up renewable energy.

Renewable Energy Potential in Bangladesh as Substantiated in Previous Studies

Bangladesh is blessed with a good amount of solar irradiance due to its geographic position. The country also generates a considerable quantity of biomass every year. Historically, people were skeptical about the possibility of utilizing wind on a large scale, attributable to the wind’s perceived low speed. On the practical implementation side, the progress of renewable energy in generating electricity has been quite low, despite the successful solar home systems program targeted for off-grid, rural people. Amid such mixed scenarios, the true potential of renewable energy in Bangladesh is often broached in different forums. Hence, the renewable energy sector of the country is an area of interest for researchers as well as local and international institutions as they try to comprehend Bangladesh’s renewable energy opportunities.

For instance, a 2010 study using a geographic information system (GIS) found 1.7% of the country’s land technically feasible for grid-connected solar projects. Considering the annual mean value of solar radiation and the efficiency of solar panels, the study concluded that the country’s solar power potential is 50,174 megawatts (MW). The research, supported by Hybrid Optimization of Multiple Energy Resources software, further estimated the wind power potential to be 4,614 MW while still factoring in the limited grid access and wind resource potential.[2] Another study conducted in 2019 estimated that Bangladesh could install a total capacity of 341,000 MW from wind and solar. The study, using GIS mapping, revealed that the country has a combined rooftop solar, utility-scale solar, and floating solar potential of 191,000 MW. Of the estimated 150,000 MW of wind power, 134,000 MW could be harnessed offshore.[3] Similarly, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) demonstrated that Bangladesh has a solar potential of 240,000 MW, assuming the possibility of utilizing 1.5% of the country’s total land.[4] Moreover, the NREL determined that Bangladesh could exploit 30,000 MW of wind power based on the results of 3.5 years of wind resource assessment, as supported by a customized GIS tool.[5] On the other hand, the important renewable energy source biomass has an alternative use in the household sector and, as such, has limited scope in power generation. Therefore, the combined potential of solar (including rooftop, utility-scale, and floating options) and wind energies, as identified in selected studies, ranges from 54,788 MW to 390,000 MW.

The Economics of Renewable Energy

Economic benefits of renewable energy. The increasing competitiveness makes a compelling case to spearhead renewable energy. Evidence shows that the cost of solar panels declined from $5 per watt in 2000 to $0.38 per watt in 2019.[6] In addition, renewable energy would help Bangladesh reduce its increasing fossil fuel import bills and thus reduce the burden on its foreign currency reserves. For instance, the installation of 2,000 MW of solar power, including utility-scale projects and industrial rooftop solar-power systems, aiming for roughly four hours for 350 days a year, could generate 2,800 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of energy. This would represent 5.8% of the gas-based energy consumption of 48,403 GWh from the national grid during 2020–21.[7] Given that 425.7 billion cubic feet (bcf) of gas were consumed by the power sector during 2020–21, the generation of 2,800 GWh of energy from solar-power systems could roughly save gas worth 24.63 bcf per annum, minimizing imported LNG equivalent to 23,792,580 metric million British thermal units (MMBtu).[8]

Similarly, replacing the 1.07 million diesel-powered pumps being used for irrigating 1.96 million hectares of land with solar-driven irrigation systems could save around 717.4 million kilograms (kg) (862.4 million liters) of diesel per annum, considering that the irrigation per hectare requires 366 kg (440 liters) of diesel. Since solar pumps would remain idle for 110 to 150 days a year when there is no demand for irrigation, grid integration of these pumps could deliver additional electricity. The replacement of 1.07 million diesel-run irrigation pumps would result in an installed solar capacity of around 4,000 MW, as each irrigation system with a 30 kilowatt-peak (kWp) solar panel capacity can replace 7.6 diesel-powered irrigation pumps.[9] Assuming a 130-day idle period in a year and the availability of solar energy for four hours a day, all solar pumps, if connected to the grid, could generate energy of 2,080 GWh. This will save 4.3% of the country’s gas-based grid electricity and reduce gas consumption by 18.3 bcf (approximately 17,677,800 MMBtu of LNG) per year. Another option could be ensuring electricity supply to all irrigation sites and generating renewable-energy-based electricity at the suitable locations with a grid integration facility to offset the electricity consumed in irrigation.

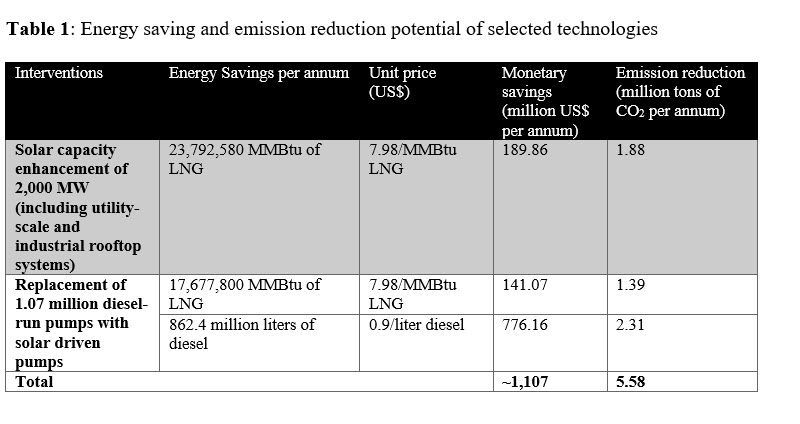

With a conservative approach, Bangladesh could annually save $1,107 million on import costs, subject to the implementation of 2,000 MW of solar capacity (utility-scale and industrial rooftop) and the replacement of all diesel-based irrigation pumps by solar-powered systems, considering a diesel price of $0.90 per liter and taking the average spot market price of $7.98 per MMBtu of LNG that Bangladesh paid before the Ukraine crisis.[10] Notably, the current LNG price in the spot market still stands at $16 per MMBtu, which demonstrates that the economic benefit of renewable energy is much higher than $1,107 million.[11] Overall emission reduction potential would be 5.58 million tons of CO2 per annum, using a grid emission factor of 0.67 tons of CO2 per megawatt-hour for replacing grid electricity and an emission factor of 2.676 kg of CO2 per liter of diesel combustion.[12] Details are furnished in Table 1.

Levelized cost of renewable energy in Bangladesh. The financial analyses, assuming a lifespan of twenty years, show that levelized cost of energy from rooftop and utility-scale solar projects stands at 5.25 Bangladesh taka (BDT) ($0.052) and 7.6 BDT ($0.076), respectively, which are less than the electricity tariff of 8.45 BDT/kilowatt-hour ($0.084) for industries before the energy price hikes of January 2023.[13] As such, both rooftop and utility-scale solar projects appear to be financially viable. On the other hand, discussions with stakeholders revealed that the levelized cost of energy from wind would be approximately 14 BDT ($0.14). Although wind energy appears to be expensive now, the decreasing trend in costs around the globe means it will be cost-competitive in the country in the foreseeable future.

Barriers to the Renewable Energy Sector

Challenges in accessing finance and the high cost of borrowing. As of now, the two most common types of financing for renewable energy in the country are the Bangladesh Bank’s green refinancing scheme, initiated in 2009, and the financing scheme of Infrastructure Development Company Limited (IDCOL).[14] But stakeholders, like local industries, project developers, and technology providers, perceive that interest rates for clean energy projects are high and that banks are not interested in financing them for a period longer than five years. Stakeholders also have the impression that the loan disbursement process is lengthy and requires numerous documents, making many entrepreneurs and project developers less interested in the projects.[15]

Nevertheless, the green refinancing scheme of the central bank has undergone changes since its inception in 2009. For instance, it now allows financial institutions to lend for a term of more than eight years. The size of the refinancing scheme has been increased from 200 crore BDT ($20 million) to 400 crore BDT ($40 million).[16] Further, in the recent modification in July 2022, green projects, including solar interventions, are eligible to receive loans from financial institutions at rates ranging from 5% to 6% depending on the loan tenor. Limits on refinance amounts have also been increased. In the case of rooftop solar-power systems in industries under net metering guidelines, the refinance amount could be up to 10 crore BDT ($1 million). A loan for a solar park could be worth up to 35 crore BDT ($3.5 million).[17] Therefore, lending terms such as interest rates and loan tenors for different renewable energies are now favorable. Yet stakeholders such as project developers, technology providers, and members of the sector association are not aware of these revisions to lending terms.

On the other hand, IDCOL lends to rooftop solar projects at a 6% interest rate. The utility-scale renewable energy projects might avail themselves of these loans at a commercial rate.[18] However, it should be noted that, in addition to the existing modes of financing, large volumes of financing over a longer period of time are necessary for the transformation of the renewable energy sector in Bangladesh. While the bond market could have been an excellent channel to meet the needs of the renewable energy sector, the market is not mature and has thus far remained thin.

Lack of complete implementation guidelines on renewable energy. Private-sector project developers are entrusted with the responsibility of arranging land and feeding the power generated from the solar park to the grid. They also construct transmission lines when the need arises. But the guidelines and information on necessary permissions, grid integration, and availability of substations, among other things, are inadequate. Stakeholders reveal cases where project proposals are submitted with the hypothesis of the availability of substations in the close vicinity of intended projects and find later that they do not exist within a reasonable distance. This ultimately increases project costs and discourages the private sector from investing. There is also the impression that project developers do not have a clear idea of the complete approval process and related timeline for a utility-scale renewable energy project.

Import duties on inverters. Applicable import duties on inverters were increased from 11% to as high as 37% in 2021.[19] This is perhaps to protect the interests of local manufacturers, but the reasons are unclear. Inverters produced locally are also of inferior quality compared to international standards.[20] This import duty affects project costs and could inhibit achieving the Mujib Climate Prosperity Plan’s recently declared target of 40% renewable energy by 2041, which was drafted in 2021 by Bangladesh when it was chair of the Climate Vulnerable Forum.[21] The plan envisions, among other things, a climate-resilient, low-carbon, and energy-secure country.

Quality of renewable energy technologies. There are widespread concerns about the quality of renewable energy-related products (e.g., solar panels and inverters).[22] Due to an absence of sufficient testing labs, ensuring the quality of imported panels becomes difficult, causing inconsistent expectations. The quality issue with solar panels results in a lack of confidence among private investors.

Overcapacity in the power sector. Bangladesh’s power sector is burdened with overcapacity. While precautionary measures owing to the high prices of fuels in the international market led by the Ukraine crisis have prompted the government to reduce power generation, even without the war, Bangladesh had lower capacity utilization rates.[23] Moreover, coal-fired power plants of 6,754 MW capacity are expected to be online within a few years.[24] Other power plants are also under construction and might further increase the power system’s overcapacity unless demand for electricity rises sharply. This might limit the space for renewable energy.

Land constraints. One of the major challenges facing renewable energy, despite its potential, is the scarcity of land in an agriculture-dependent and densely populated country. In particular, utility-scale projects require large tracts of land that are often difficult to find. There have been examples where investors struggled to find suitable land for a project.[25]

Building Renewable Energy without Affecting Agricultural Land

Different studies substantiate the high potential of solar and wind energy in Bangladesh but also conclude that tapping this opportunity is not possible unless land for utility-scale projects becomes available. A closer inspection, however, suggests that sizable amounts of solar energy could be harnessed from the rooftops of industrial and commercial buildings. Alongside this, the country has already allocated, or is in the process of allocating, land for some 97 special economic zones that would accommodate diversified industries to expedite economic growth and enhance employment opportunities.[26] Rooftop and utility-scale solar projects could be implemented in these economic zones. Additionally, identification of available barren lands, including areas within the public sector, and assessment of char areas (islands) to differentiate stable land appropriate for renewable energy projects could significantly ramp up renewable energy capacity.

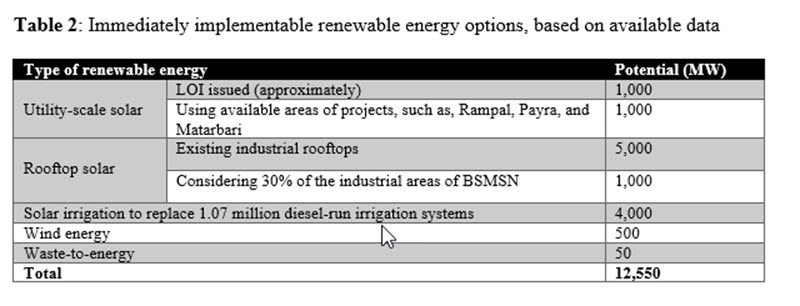

A review of published documents and discussions with sector experts reveal that approximately 2,000 MW of utility-scale solar projects could be immediately implemented, of which a letter of intent has been issued for projects of around 1,000 MW capacity. The remaining capacity of 1,000 MW could be installed in available project areas, like Rampal, Payra, and Matarbari. Industrial rooftops could also accommodate around 5,000 MW of solar-power systems.[27] Additionally, the designated industrial area for the Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Shilpa Nagar (BSMSN) development project is 14,000 acres, and using 30% of the rooftops of future industries in this area, at least 1,000 MW of solar capacity could be harnessed.[28] Besides, the replacement of 1.07 million diesel-run irrigation pumps would result in an installed solar capacity of around 4,000 MW, as each irrigation system with a 30 kWp solar panel capacity can replace 7.6 diesel-powered irrigation pumps.[29]

Moreover, planned wind energy projects have a combined capacity of more than 500 MW.[30] Agreements have also been signed for waste-to-energy projects of approximately 50 MW capacity.[31] Therefore, on the basis of available information, a renewable energy capacity of 12,550 MW could be exploited over the next few years without hindering agricultural production (see Table 2). However, only proper land resource mapping can delineate the exact renewable energy opportunities in Bangladesh.

Furthermore, the country has about one million hectares of islands (i.e., lands developed across the river bank or on the riverbed as a result of sediment accretion).[32] Even 1% of the islands (around 10,000 hectares) would be enough for the installation of over 6,000 MW of solar power, provided the lands are stable and grid integration is straightforward. Since 97 economic zones are in different stages of development, combining the available areas of these zones could allow the development of significant renewable energy, which should be carefully evaluated at the initial stage to avoid implementation challenges in the future.

Financing Mechanisms to Spearhead Renewable Energy

Two major funding sources to promote renewable energy in Bangladesh are the central bank’s green refinancing scheme and IDCOL’s loans. However, to ramp up the capacity of renewable energy, especially in line with the government’s renewed focus, Bangladesh needs increasing volumes of financing from additional sources. This section explores different financing options for renewable energy.

Green bonds and green sukuk. Green bonds raise proceeds to fund green projects, including clean energy. Green sukuk (financial certificates) operate in the same manner, with the exception that instead of fixed interest, the income of investors follows Sharia principles (Islamic law).[33] Both green bonds and green sukuk can generate financing for large clean energy projects. While the first green sukuk of its kind was issued in June 2017, the annual issuance of the instrument increased to $4 billion in 2019. From 2017 to September 2020, green sukuk worth $10 billion were issued in Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Malaysia.[34] In a recent case, a green sukuk amounting to 30 billion BDT ($300 million) was issued for the development of a 230 MW capacity solar project in Bangladesh.[35] The successful issuance of green sukuk for renewable energy would be an excellent basis for generating finance for large-scale renewable energy projects.

Likewise, the potential of green bonds can be tapped to minimize financial barriers to large-scale renewable energy projects and catalyze renewable energy investment at scale. In that regard, the policy on green bond financing developed by the Bangladesh Bank in September 2022 provides the necessary framework for the issuance of green bonds and utilizing the proceeds for green projects, including renewable energy. The policy also includes a green bond taxonomy and clear eligibility criteria for different green activities.[36] This policy could, in fact, stimulate the development of the green bond market in Bangladesh, which is otherwise thin, and help spur clean energy promotion.

Utilization of the full potential of IDCOL. As a non-bank financial institution, IDCOL has a track record of lending to renewable energy projects, both small and utility-scale. In particular, the solar home systems program has been a highlight of IDCOL’s operation and helped install 4.13 million solar-power systems in off-grid areas by January 2019. It has lending programs for other renewable energy projects, like solar irrigation, solar rooftop, solar mini-grids, and utility-scale solar. It also has access to low-cost financing from multilateral agencies.[37] Additionally, IDCOL is an accredited entity of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and had its funding proposal approved by the GCF for implementing an energy efficiency project in the garment and textile industries.[38] Similarly, it can develop renewable energy projects supported by low-cost financing from the GCF. Therefore, IDCOL has the capacity to catalyze a large volume of financing for the renewable energy sector, making it a competent agency for the sector.

The Super Energy Service Company (ESCO) model. It is necessary to not only channel an increasing volume of financing to shore up renewable energy capacity but also maintain the quality of implementation. In this vein, an important stepping stone could be establishing a company with adequate renewable energy financing and project implementation capacity. A “Super ESCO”—a government-backed entity that addresses the challenges of energy efficiency projects starting from project design, procurement, implementation, monitoring, and verification—is an example.[39] Apart from energy efficiency projects, the Super ESCO of India (Energy Efficiency Services Limited) has been supporting solar projects in different establishments, including industries.[40] Being a government company, the Super ESCO helps arrange low-cost international financing and utilizes public financing for the growing number of projects. Bulk procurement of renewable energy equipment might help reduce the cost as well.

Funding from multilateral agencies. Multilateral agencies such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB), and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) have clear visions to promote clean energy in developing countries. For instance, the World Bank recently signed a $515 million agreement with the government of Bangladesh to support the country in its clean energy transition by developing battery storage systems and distributed renewable energy.[41] In May 2022 the AIIB extended a $200 million long-term credit line to Bangladesh under which IDCOL will on-lend to eligible projects renewable energy, energy efficiency, and related projects.[42] The ADB provides similar loans. Both IDCOL and a newly established Super ESCO could secure credit lines from multilateral agencies for on-lending to suitable renewable energy projects in Bangladesh.

Operational expenditure (OPEX) model. Many facility owners with an interest in rooftop solar projects find that they are incapable of arranging debt financing from financial institutions or face difficulty in preparing the required documents to obtain a loan to purchase and install a solar panel system. To that end, an OPEX model could be a viable alternative. In an OPEX model, the service companies shoulder all responsibilities for arranging loans and supplying and installing the systems and would sell solar energy to a facility owner at an agreed-on rate lower than the government’s existing electricity tariff for a period of years from the date of commission. This period would allow the service provider to collect enough revenue to pay the debt service to the financial institution and make a reasonable profit. Following that, the service provider hands over the project to the facility owner.

However, service providers might also experience challenges accessing finance from financial institutions for an increasing number of projects. To simplify the process, the central bank could introduce a rating system for the service providers, prepare a list of high-quality service providers, and periodically review the performance of the service providers. Financial institutions could swiftly approve loan proposals for rooftop solar projects submitted by service providers included on the central bank’s list in an OPEX model. In addition, service providers might be able to extend implementation support to both rooftop and utility-scale projects contingent on the establishment of a national Super ESCO.

Measures and Policy Instruments to Enhance the Share of Renewable Energy

The presence of barriers, as analyzed in the preceding section, shows the necessity of providing policy-level support to the renewable energy sector. It is also essential to design policy instruments and financing mechanisms that have the capacity to address prevailing barriers. Approved net metering guidelines incentivize the uptake of rooftop solar-power systems in both industrial and commercial buildings. Given the competitiveness of solar and wind technologies and their cost reduction trends, a feed-in tariff is inessential at this stage. Rather, enhancing competition in grid-tied projects could be an option for Bangladesh. Moreover, the government should have a time-bound action plan in place for renewable energy development. This section summarizes the policy instruments and other measures that could help realize Bangladesh’s increased ambitions for renewable energy.

Assessment of true renewable energy potential and earmarking land. Mapping land could be carried out to evaluate the feasible potential of different renewable energies throughout the country, starting with rooftop solar, utility-scale solar, floating solar, wind, and others, while avoiding impacts on agricultural production or local communities. Local communities should not be forcibly displaced, and alternative climate-resilient generation options should be made available to them. Location details of eligible land could be documented and published on the websites of the relevant government agencies so as to ensure information dissemination and attract private project developers to invest in utility-scale renewable energy projects.

Time-bound action plan for renewable energy development. A time-bound action plan on renewable energy development would include, among other things, yearly goals for renewable energy based on types, the resource requirement from the government side, the roles of different government agencies, and monitoring mechanisms. This would help accelerate renewable energy projects and signal to investors, technology providers, and financial institutions what the government’s renewable energy vision entails.

Integrated energy and power master plan. The integrated energy and power master plan of Bangladesh, as opposed to separate energy sector and power sector plans, is currently being formulated. The integrated master plan should reveal the net benefits of renewable energy development in Bangladesh compared with the country’s dependence on imported fossil fuels, which has already exposed the country to price volatility in the international market. In spite of having enough power-generation capacity, the high price of fossil fuels has forced the government to apply precautionary measures, like load shedding. The power and energy systems that Bangladesh currently maintains would be affected in the case of a future global fuel market disruption too. Hence, the integrated master plan should provide the stepping stones needed to reduce reliance on imported fossil fuels by increasing the share of renewable energy to avoid a future energy supply crunch.

Plan for phasing out idle, inefficient, and least-economic plants. Bangladesh needs to carefully assess the costs of keeping power plants idle or operating at a lower capacity. Fossil fuel–based power plants that are under construction may increase the overcapacity of the sector. Notably, highly volatile and expensive imported fossil fuels resulted in a bulk electricity price hike of nearly 20% last year.[43] Consequently, electricity tariffs were raised twice by 5% in January 2023.[44] A plan, therefore, could be developed to gradually phase out idle, inefficient, and least-economic power plants and reduce power sector overcapacity to open up space for cost-competitive renewable energies. This would help the government operate a mix of power plants that could ensure least-cost generation.

Guidelines for renewable energy project implementation. Attaining a 40% renewable energy target hinges on the rapid implementation of projects on the ground. This necessitates having complete guidelines for renewable energy projects on the required permissions and their timelines, power evacuation, and grid integration, among other factors. The government agencies should make information on the locations of substations available so that project developers can have a clear understanding of the availability of substations within an acceptable distance from proposed renewable energy project sites.

Waiver of import duties on inverters. From the perspective of private investors, the removal of duties on imported inverters to make renewable energy projects more competitive is logical. For years, stakeholders in the renewable energy sector have been raising this matter, inviting the government to intervene and waive duties.

Establishment of a Super ESCO. Establishing a government-backed Super ESCO would entail developing and approving a legal framework that allows it to operate as a company. This would require setting up an institutional structure with sufficient technical capacity to evaluate, finance, implement, and monitor clean energy projects. Overall, the formation of a Super ESCO could be part of the government’s broader vision to increase the share of renewable energy to 40% by 2041.

Monitoring of green finance by the central bank. The green banking policy of the Bangladesh Bank has directed banks and financial institutions to maintain a direct green finance quantity of at least 5% of their disbursed loans. On a quarterly basis, banks and other financial institutions are required to report to the central bank on their green financing portfolios.[45] Nevertheless, stakeholders in the renewable energy sector find bankers less interested in financing green projects, including renewable energy interventions. One solution could be the strict monitoring of the financial institutions’ green financing activities and ensuring compliance with the target of at least 5% of loans to green projects against their total loan disbursement, as set out by the central bank.

Introduction of auctions. Competition among project developers around the globe has been key to the drastic reduction of renewable energy costs over the last decade. Different countries have introduced public auctions to lower the price of renewable energy. In Bangladesh, utility-scale renewable energy projects are being implemented based on unsolicited proposals submitted by private entities. Introducing auctions instead would enhance competition among the project developers and thus make solar energy (and perhaps wind power) even cheaper. In public auctions, there are examples of technical failures and lower plant performance. As such, defining technical requirements, adopting international standards, and monitoring compliance with international standards are needed when designing public auctions. Bangladesh shall, therefore, develop public auction guidelines for renewable energy projects, including technical specifications.

Grid stability. As the share of variable renewable energy grows, increased focus is given to grid stability. However, only just over 1% of the national grid’s electricity was generated from renewable energy sources during fiscal year 2020–21. When hydropower is excluded, the share of renewable energy drops to a meager 0.2%.[46] In light of the proposed goal of harnessing 40% renewable energy by 2041, adequate measures should be taken to enhance national grid stability. A detailed study is required to assess the condition of the grid and how stable voltage and frequency would be maintained with the increasing integration of highly variable renewable energies.

Accredited testing labs. Amid widespread concerns over quality, the government can take steps to support the establishment and accreditation of labs in academic institutions for testing renewable energy equipment, such as solar panels. This model is already applied in technical testing services provided by technical universities to public and private agencies in different sectors. Proper testing of solar panels and quality assurance would boost the confidence of investors and potentially increase investment in the sector.

Conclusion

Renewable energy in Bangladesh has a compelling economic case due to not only its low cost but also the exigencies to transform the power sector of the country by reducing import dependence. This essay substantiates the economic benefits of developing both rooftop solar and utility-scale projects to contain LNG and other fossil fuel imports and replacing diesel-based irrigation pumps with solar-powered systems. It furthermore exhibits that the levelized costs of energy from both rooftop solar and utility scale solar projects are less than the electricity tariff of industries. However, fulfilling the renewable energy target of 40% by 2041, as per the draft Mujib Climate Prosperity Plan, involves allocating suitable land for utility-scale renewable energy projects. To that end, land resource mapping is key, and the government should explore the viability of using available areas in planned economic zones as well as islands.

Alongside these measures, policy-level interventions such as preparing a renewable energy action plan; phasing out inefficient, idle, and costly power plants; removing duties on imported inverters; addressing the challenges of financing; introducing competitive auction mechanisms; ensuring grid stability; and establishing adequate testing labs for renewable energy equipment will help expedite the promotion of renewable energy.

Shafiqul Alam is a Clean EDGE Asia Fellow at the National Bureau of Asian Research. He has more than a decade of experience in energy and climate change sectors. He is an engineer turned environmental economist.

Endnotes

[1] Shafiqul Alam, “Toward a Sustainable Energy Pathway for Bangladesh,” National Bureau of Asian Research, Clean EDGE Asia, August 4, 2022, https://www.nbr.org/publication/toward-a-sustainable-energy-pathway-for-bangladesh.

[2] Md. Alam Hossain Mondal, “Implications of Renewable Energy Technologies in the Bangladesh Power Sector: Long-Term Planning Strategies,” Rhenish Friedrich Wilhelm University of Bonn, Faculty of Agriculture, July 22, 2010, available at https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/biblio/21430229.

[3] Sven Teske, Tom Morris, and Kriti Nagrath, “100% Renewable Energy for Bangladesh: Access to Renewable Energy for All within One Generation,” World Future Council, August 29, 2019, https://www.worldfuturecouncil.org/100re-bangladesh.

[4] U.S. Agency for International Development, “Renewable Energy Implementation Action Plan: Recommendations for Bangladesh,” March 2011, https://www.usaid.gov/energy/sure/bangladesh/re-action-plan.

[5] Mark Jacobson et al., “Assessing the Wind Energy Potential in Bangladesh: Enabling Wind Energy Development with Data Products,” National Renewable Energy Laboratory, September 2018, https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy18osti/71077.pdf.

[6] Max Roser, “Why Did Renewables Become So Cheap So Fast?” Our World in Data, December 1, 2022, https://ourworldindata.org/cheap-renewables-growth.

[7] Bangladesh Power Development Board, Annual Report 2020–21 (Dhaka, October 2021), https://bpdb.gov.bd/site/page/c4161d54-5b85-4917-a8d2-68a2d1b26dd4/Monthly-Annual-Report.

[8] Bangladesh Hydrocarbon Unit, Annual Report on Gas Production, Distribution and Consumption 2020–21 (Dhaka, December 2021), http://www.hcu.org.bd/site/publications/10d6d5dd-7be6-443d-9c2e-5b01f3f44dc9/Annual-Report-on-Gas-Production-Distribution-and-Consumption-2020-21; and “Approximate Conversion Factors: Statistical Review of World Energy,” BP, July 2021, https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2021-approximate-conversion-factors.pdf.

[9] Archisman Mitra, Mohammad Faiz Alam, and Yashodha Yashodha, “Solar Irrigation in Bangladesh: A Situation Analysis Report,” International Water Management Institute, September 2021, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363639611_Solar_Irrigation_in_Bangladesh_A_Situation_Analysis_Report.

[10] Khondaker Golam Moazzem, Abdullah Fahad, and Shah Md. Ahsan Habib, “Economic and Environmental Cost Estimation of LNG Import: Revisiting the Existing Strategy of Imported LNG,” Centre for Policy Dialogue, Working Paper, no. 144, June 2022, https://cpd.org.bd/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Economic-and-Environmental-Cost-Estimation-of-LNG-Import.pdf.

[11] Emily Chow, “Refile-Global LNG-Asia Spot Prices Slip for Ninth Week as Demand Remains Weak,” Reuters, February 17, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/article/global-lng/refile-global-lng-asia-spot-prices-slip-for-ninth-week-as-demand-remains-weak-idUSL1N34X0Q7.

[12] Department of Environment (Bangladesh), “Grid Emission Factor (GEF) of Bangladesh,” August 19, 2013, http://www.doe.gov.bd/site/notices/059ddf35-53d3-49a7-8ce6-175320cd59f1/Grid-Emission-Factor(GEF)-of-Bangladesh; and Greenhouse Gas Protocol, “Emission Factors from Cross-Sector Tools,” March 2017, https://ghgprotocol.org/calculation-tools.

[13] “BERC Order No. 2020/02, Bangladesh Bidyut Unnoyon Board (BUB) er Khuchra Mullohar Adesh” [Tariff Order for Retail Electricity Price of Bangladesh Power Development Board (PDB)], Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission, February 27, 2020.

[14] “ACSPD Circular No. 06, Shoura Shakti, Bayogas o Borjo Porishodhon Plant Khate Punoh Orthayon Scheme” [Refinance Scheme for Solar Energy, Biogas, and Effluent Treatment Plant Sectors], Bangladesh Bank, August 3, 2009; and “Renewable Energy: Eligible Sectors,” IDCOL, https://idcol.org/home/r_eligibility.

[15] Shafiqul Alam, “Tapping the Benefits of Solar Rooftop Projects under Net Metering in Bangladesh: A Capacity Needs Assessment Study,” Appropriate Technology 48, no. 3 (2021): 52–55.

[16] “SFD Circular No. 02, Poribeshbandhob Ponno/Udyog/Prokolper jonno Punoh Orthayon Scheme” [Refinance Scheme for Green Products/Projects/Initiatives], Bangladesh Bank, April 30, 2020; and “GBCSRD Circular Letter No. 02, Poribeshbandhob Ponno/Udyog/Prokolper jonno Punoh Orthayon Scheme” [Refinance Scheme for Green Products/Projects/Initiatives], Bangladesh Bank, July 1, 2013.

[17] “SFD Circular No. 04: Poribeshbandhob Ponno/Udyog/Prokolper jonno Punoh Orthayon Scheme” [Refinance Scheme for Green Products/Projects/Initiatives], Bangladesh Bank, July 24, 2022.

[18] “Rooftop Solar Project,” IDCOL, https://idcol.org/home/rooftopsolar; and “Lending Terms,” IDCOL, https://idcol.org/home/r_lending_terms.

[19] Syful Islam, “Restoration of Full Customs Duties for Inverters Hits Bangladeshi Solar Sector,” pv magazine, September 3, 2021, https://www.pv-magazine.com/2021/09/03/restoration-of-full-customs-duties-for-inverters-hits-bangladeshi-solar-sector.

[20] “Prohibitive Taxing Stymies Green Power Expansion,” Financial Express, March 12, 2022, https://today.thefinancialexpress.com.bd/last-page/prohibitive-taxing-stymies-green-power-expansion-1647021709.

[21] Government of Bangladesh, Mujib Climate Prosperity Plan: Decade 2030 (Dhaka, September 2021), https://mujibplan.com.

[22] Syful Islam, “Bangladesh Needs More Labs to Check Quality of Solar Imports,” pv magazine, February 17, 2022, https://www.pv-magazine.com/2022/02/17/bangladesh-needs-more-labs-to-check-quality-of-solar-imports/.

[23] Simon Nicholas, “Bangladesh’s Power System Overcapacity Problem Is Getting Worse,” Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), January 1, 2021, https://ieefa.org/resources/bangladeshs-power-system-overcapacity-problem-getting-worse.

[24] Shafiqul Alam, “For Security and Affordability, Bangladesh Must Shore Up Renewable Energy,” IEEFA, November 18, 2022, https://ieefa.org/resources/security-and-affordability-bangladesh-must-shore-renewable-energy.

[25] Md. Tahmid Zami, “Analysis: In Bangladesh, Solar Power Brings Work, but Land Shortage Slows Growth,” Reuters, August 24, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/bangladesh-solar-power-brings-work-land-shortage-slows-growth-2022-08-24.

[26] Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority, “Economic Zones Site,” https://www.beza.gov.bd/economic-zones-site.

[27] “5,000MW Solar Power Achievable from Industrial Rooftops,” Business Standard, October 24, 2020, https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/energy/5000mw-solar-power-achievable-industrial-rooftops-149302.

[28] Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority, “Economic Zones Site,” https://www.beza.gov.bd/economic-zones-site; and author’s calculation.

[29] Archisman Mitra, Mohammad Faiz Alam, and Yashodha, “Solar Irrigation in Bangladesh: A Situation Analysis Report,” International Water Management Institute, September 2021, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363639611_Solar_Irrigation_in_Bangladesh_A_Situation_Analysis_Report.

[30] Jobaer Chowdhury and Eyamin Sajid, “Country’s First Big Leap in Wind Energy from December,” Business Standard, July 21, 2022, https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/energy/countrys-first-big-leap-wind-energy-december-462702.

[31] “Chinese Firm to Build 42.5MW Waste-to-Power Plant in Gazipur,” Business Standard, December 8, 2021, https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/energy/chinese-firm-build-425mw-waste-power-plant-gazipur-340753; and “Agreement Signed to Set up Bangladesh’s 2nd Waste-to-Energy Project,” Daily Star, September 1, 2022, https://www.thedailystar.net/environment/natural-resources/energy/news/agreement-signed-set-bangladeshs-2nd-waste-energy-project-3108711.

[32] Md. Abdul Karim et al., “Challenges and Opportunities in Crop Production in Different Types of Char Lands of Bangladesh: Diversity in Crops and Cropping,” Tropical Agriculture and Development 61, no. 2 (2017): 77–93.

[33] “Pioneering the Green Sukuk: Three Years On,” World Bank, October 6, 2020, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/malaysia/publication/pioneering-the-green-sukuk-three-years-on.

[34] “Asian Development Outlook (ADO) 2021: Financing a Green and Inclusive Recovery,” Asian Development Bank (ADB), April 2021, https://www.adb.org/publications/asian-development-outlook-2021.

[35] “Beximco Green-Sukuk Al Istisna’a of BDT 30.0 Billion: 9%++ Convertible/Redeemable Asset Backed Green-Sukuk,” Beximco Green Sukuk Trust, https://bexgreensukuk.com.

[36] “Policy on Green Bond Financing for Banks and FIs,” Bangladesh Bank, September 2022.

[37] “Solar Home System Program,” IDCOL, https://idcol.org/home/solar.

[38] “Infrastructure Development Company Limited (Bangladesh),” Green Climate Fund, https://www.greenclimate.fund/ae/idcol.

[39] Ashok Sarkar and Sarah Moin, “Transforming Energy Efficiency Markets in Developing Countries: The Emerging Possibilities of Super ESCOs,” World Bank, Live Wire January 9, 2018, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/536121536259648570/Transforming-Energy-Efficiency-Markets-in-Developing-Countries-The-Emerging-Possibilities-of-Super-ESCOs.

[40] “Decentralized Solar Power Plant Programme,” Energy Efficiency Services Limited, https://eeslindia.org/en/decentralized-solar.

[41] “Bangladesh: World Bank Supports Reliable Electricity Supply, Clean Energy for 9 Million People,” World Bank, June 29, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/06/29/bangladesh-world-bank-supports-reliable-access-to-electricity-supply-clean-energy-for-9-million-people.

[42] Syful Islam, “Bangladesh Secures $200M from Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank to Support Renewables,” pv magazine, May 9, 2022, https://www.pv-magazine.com/2022/05/09/bangladesh-secures-200m-from-asian-infrastructure-investment-bank-to-support-renewables.

[43] “Bulk Electricity Price Hiked by 19.92%,” Business Standard, November 21, 2022, https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/energy/bulk-electricity-price-hiked-1992-535978.

[44] “Bangladesh Hikes Power Price Again in Less than Three Weeks,” New Age, January 31, 2023, https://www.newagebd.net/article/193170/bangladesh-hikes-power-price-again-in-less-than-three-weeks.

[45] Monzur Hossain, “Green Finance in Bangladesh: Policies, Institutions, and Challenges,” ADB Institute, Working Paper, no. 892, November 2018, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/467886/adbi-wp892.pdf.

[46] Bangladesh Power Development Board, Annual Report 2020–21.