Interview

AUKUS Pillar II: Speed, Innovation, and Expansion

In Part II of a two-part interview, Rear Admiral Lee Goddard turns to Pillar II of the AUKUS agreement between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The second pillar centers on advanced technology cooperation across quantum computing, artificial intelligence, cyber capabilities, undersea systems, and hypersonics. The conversation highlights the urgency of accelerating capability delivery, eliminating regulatory and cultural barriers, and adopting innovative cycles that match the speed of strategic competition. RADM Goddard also details the potential to expand AUKUS beyond the three founding members to include like-minded partners such as Japan, South Korea, Canada, and New Zealand.

Pillar II of AUKUS emphasizes collaboration on advanced technologies such as quantum computing, artificial intelligence, cyber capabilities, and hypersonic systems. What progress have the AUKUS partners made in joint development and integration of these technologies, and what obstacles remain to achieving full interoperability?

Progress has been made in strengthening collaboration among the militaries, defense departments, and defense science and innovation sectors of Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Although less visible, this culture of exchange is essential to achieve Pillar II. Much of the progress to date involves the reduction of both passive and active barriers to cooperation.

In regard to regulation, efforts have focused on minimizing obstacles such as the U.S. International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), which, while essential for safeguarding security, nonproliferation, and intellectual property, have historically constrained the flow of technology and expertise. These restrictions have been especially significant for Pillar I in relation to the Virginia-class submarines, where Australia is seeking access to sensitive nuclear propulsion technologies, and for Pillar II in emerging domains such as quantum computing, cyber, and hypersonics, where both Australia and the UK aim to integrate U.S. innovations more quickly into joint projects.

Active steps have also been taken to align the industrial, academic, and innovation ecosystems across the three countries. Industrial partnerships and university research collaborations have created pathways for more effective integration. For example, Lockheed Martin Australia and the Defence Science and Technology Group have partnered on advanced defense technologies, including hypersonics, while the University of Sydney has received major national support to build out a quantum ecosystem that works closely with industry. Likewise, the University of Oxford has made significant advances in distributed quantum computing, and the University of New South Wales has spun out Diraq, a company developing scalable quantum computing solutions.

Yet, even as these initiatives illustrate the growing alignment of research and innovation across AUKUS, often overlooked cultural barriers persist in the form of hesitancy among personnel to share information due to unclear guidelines. Addressing these concerns and reinforcing the permissibility and necessity of collaboration is thus of utmost importance.

Additionally, despite these positive developments, tangible demonstrations under Pillar II have yet to emerge. Although promising programs are underway, current geopolitical dynamics demand visible outcomes. Leaders outlining Pillar II must be able to show concrete technologies, not just frameworks. Without this, AUKUS risks being seen as overly bureaucratic at a time when impact is necessary.

Extensive behind-the-scenes work has been carried out, and the efforts of those in government and defense are commendable. However, in Australia public discourse increasingly questions whether current defense strategies and capabilities are calibrated to the pace of emerging threats. Concerns have been raised that defense posturing remains focused toward the 2035–40 timeframe, while strategic risks may arrive as early as 2027. Readiness must align with that reality.

In some cases, higher costs are delivering fewer results. Pillar II should serve as a mechanism to accelerate the deployment of proven technologies, particularly in autonomy, cyber, undersea warfare, and hypersonics, where knowledge and capability already exist. These are not conceptual ideas for the future; they are operational realities that require immediate action and effective communication.

Australia’s objective is clear, it must ensure that defense personnel have access to the most advanced military and dual-use technologies at the same time as their American and British counterparts. This includes access not only to initial capabilities but also to upgrades, improvements, and collaborative development. That is the strategic promise and necessity of Pillar II. It represents a significant opportunity, but one that is moving too slowly. The current moment demands urgency and action.

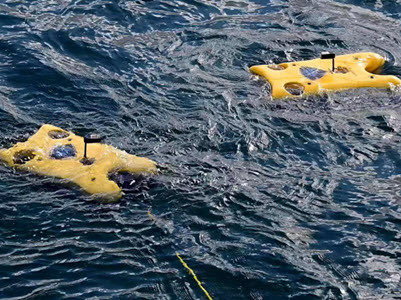

In 2024 the AUKUS partners conducted their first trilateral innovation challenge focused on autonomous undersea warfare, marking an important milestone in reaching Pillar II objectives. Looking ahead, what are the most promising near-term deliverables under Pillar II, and how are the AUKUS partners prioritizing specific technologies for joint development, testing, and potential fielding?

The trilateral innovation challenge was a meaningful milestone, and an example of the types of mechanisms needed to drive progress. However, a fundamental shift in mindset around timelines is necessary. Rather than planning in nine-year increments, partners should consider nine-month, nine-week, or even nine-day cycles when feasible.

While some technologies, such as quantum computing, require longer development due to their complexity, many Pillar II technologies are not theoretical. These technologies already exist and are operational. The focus must shift from invention to rapid integration and deployment. In fields like artificial intelligence, electronic warfare, cyber defense, and autonomy, the obstacles are primarily bureaucratic and organizational rather than technical.

Quantum computing remains an exception, with massive implications for cryptology and secure communications. Quantum technologies could determine the ability to decipher current encryption and secure future networks. This domain resembles a modern-day Manhattan Project and demands similar urgency.

Pillar II should act as a technological offset strategy that enables the AUKUS partners to maintain an edge over potential adversaries. Historically, the United States has relied on such strategies to preserve strategic advantage. AUKUS provides an opportunity to share that edge trilaterally, and Australia must fully embrace that opportunity.

Speed-to-capability should serve as an important metric. In the rapidly evolving operational environment, a bias toward action is critical—fielding a system that is “good enough” today, then improving on it. This model requires expanding beyond traditional government acquisition models. Innovation in the commercial, academic, and venture capital sectors must be leveraged. There is a growing base of private capital interested in defense and dual-use technologies, not only for return on investment but also for a sense of national purpose. These actors recognize that national security requires a whole-of-society approach.

While the trilateral innovation challenge was a positive start, additional initiatives in electronic warfare and other emerging domains must follow. Pillar II will succeed only if speed and relevance become core organizing principles.

Japan and South Korea are frequently mentioned as potential contributors and participants in AUKUS in areas such as advanced technology development and integration. Canada and New Zealand, with their close defense ties and Five Eyes alignment, could offer complementary capabilities. Is expanding AUKUS to include Japan, South Korea, Canada, or New Zealand under a broader AUKUS+ framework a feasible path forward?

Expansion of Pillar II is both feasible and appropriate. While Pillar I is centered on nuclear propulsion and remains exclusive to the three founding members, Pillar II offers a more flexible framework for cooperation. Public statements already show interest in engagement with partners such as Japan, Canada, and New Zealand. At the same time, their formal inclusion has not yet occurred due to several factors. These include the need to first establish internal cohesion among the three AUKUS partners, ongoing challenges related to export control alignment and information sharing, and political sensitivities in managing China’s reaction to any perceived enlargement of the partnership.

Canada and New Zealand, as members of the Five Eyes intelligence alliance, already possess many of the security and information-sharing protocols necessary for deeper collaboration. However, the foundation of Pillar II among the core AUKUS members must be strengthened before meaningful expansion occurs. New Zealand and Canada also bring trusted capabilities, shared values, and a long history of cooperation. South Korea adds distinct technical strengths and regional relevance.

A phased approach would likely be the most effective. Project-specific collaborations could serve as initial test cases: one initiative with Japan, another with South Korea, and separate engagements with Canada and New Zealand. These pilot programs would help test interoperability and refine coordination. Among the potential partners, Japan’s industrial base and strategic alignment make it a compelling candidate for engagement in the near term. While acronyms like “JAUKUS” may be premature, formal designation of Japan as a key Pillar II partner would be a positive step.

In summary, expanding AUKUS under a “Pillar II+” framework would provide a strategic advantage and is achievable. The priority should be to ensure that the foundational trilateral cooperation delivers concrete outcomes. Once established, expansion to include like-minded partners should proceed, while continuing to emphasize interoperability, capability sharing, and shared security goals.

Rear Admiral Lee Goddard is the former Commander of Australia’s Maritime Border Command and a current board member of Austal and advisor to Saronic Technologies.

This interview was conducted by Bruno Hernandez Sotres, who is a project manager with the Political and Security Affairs group at NBR.

Related Q&A: AUKUS Pillar I: Commitments, Capabilities, and Continuity