The war in Ukraine may be Russia’s most blatant attempt to undermine the sovereignty and territorial integrity of a neighboring state, but it is in keeping with a long history of Russian attempts to dominate its smaller neighbors. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Russian Federation has remained deeply enmeshed in the political and economic affairs of the other post-Soviet states. Perceiving Russia both as a great power in a world dominated by the amoral interactions of great powers and as the heir to a long imperial legacy, the security service veterans (known as siloviki) who constitute the core of Vladimir Putin’s regime regard the idea of dominating the smaller states around Russia’s borders as normal and even natural. As during the Cold War, many of them also see the maintenance of a regional sphere of “privileged interests” as part of a wider strategic competition with the U.S.-led West.1

Russian officials and commentators typically avoid providing a precise definition of where this sphere is located, or what interests precisely Moscow considers privileged within it. In practice, Russian influence radiates out in something like concentric circles, varying according to the respective geographic, strategic, and cultural importance Moscow assigns to its former dependencies. Yet this sphere is not always geographically bounded. Rather, Russia uses a range of hard and soft power tools to project influence within and beyond the borders of the former Soviet Union, guided by a sense of its own unique destiny and a commitment to limiting the spread of Western political and social models.

The Sources of Russian Influence

Russian attempts to maintain dominion over its neighbors rest on a perception of two-tiered sovereignty: while insisting on absolute sovereignty for itself (including the right to determine which foreign entities are allowed to operate on its soil), Russia considers the sovereignty of the states comprising its “near abroad” limited and conditional.2 Across the former Soviet Union, Moscow deploys troops, manipulates ethno-territorial conflicts, cultivates pro-Russian elites, engages in information operations, and promotes Russocentric multilateralism. Such intervention aims at protecting kleptocratic political systems that remain susceptible to Russian influence and preventing or limiting post-Soviet states’ cooperation or integration with Euro-Atlantic institutions.

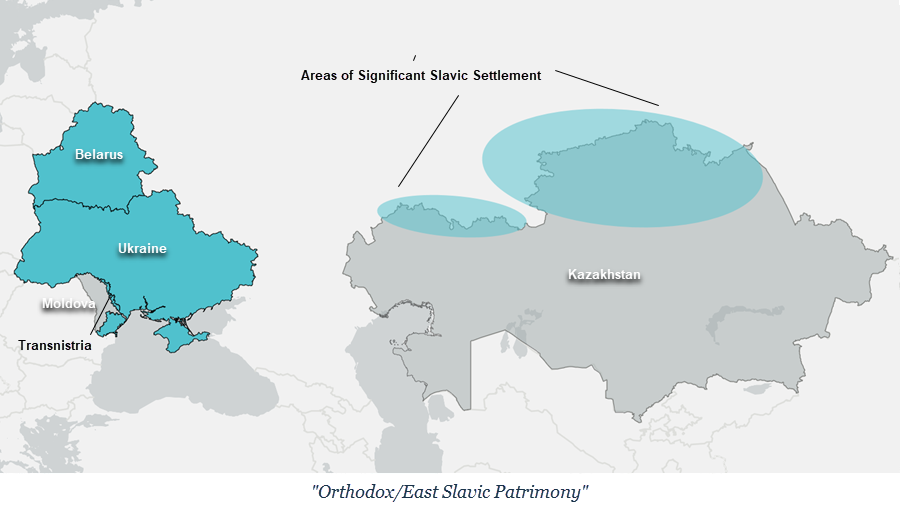

The Kremlin’s highest priority remains Ukraine and other Orthodox-majority, East Slavic states and regions—including Belarus, Moldova’s separatist region of Transnistria, and the northern part of Kazakhstan. Next is an inner core of states—Armenia, Kazakhstan, and arguably Kyrgyzstan—that retain deep economic, political, and security ties to Russia through both the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Moscow regards the remaining states of the South Caucasus and Central Asia—i.e., Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan—as a kind of outer periphery, mostly left to their own devices as long as they remain stable and do not countenance too much Western influence.3

Russian ambitions are not, however, confined to the borders of the former Soviet Union. Amid its deepening strategic confrontation with the United States, Moscow has devoted increasing attention to the idea of a Russocentric “Greater Eurasia” as a geopolitical antipode to the U.S.-centric West. This idea of Eurasia as an alternative international order has strong echoes of the Cold War, which is held up by its most ardent proponents as a template for how Russia should relate to the Euro-Atlantic world today. In Russian geopolitical thought, Greater Eurasia is geographically fluid, encompassing multilateral frameworks as well as agreements with individual states that Moscow seeks to incorporate to a greater or lesser degree in this idealized non-Western order.

Across both the former Soviet Union and Eurasia more broadly, Moscow emphasizes not merely political and institutional arrangements, but also what it refers to as “traditional” values—an amalgam of anti-liberal ideas with a strong mystical underpinning and associated with the idea of the “Russian world” promoted by the leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church.4 The Kremlin, the Church, official media, and associated quasi-nongovernmental organizations (QUANGOs) all promote Russia’s “brand” as the avatar of “traditional” values supposedly threatened by Western elites. The ensuing hostility to LGBT rights, feminism, multiculturalism, and the like represents a deliberate strategy for appealing to populations at home and abroad who are disaffected with liberal modernity. It also reflects the decimation of Russia’s own intellectual heritage under Communist rule—a decimation that similarly affected other states subjected to Soviet/Communist domination.

The East Slavic “Patrimony”

Russian officials and elites regard the Orthodox, East Slavic states and regions as part of Russia’s own historic patrimony (votchina), and their political independence as essentially a historical accident to be remedied. Reflecting tsarist-era notions about Russian identity, belief in the common character and destiny of Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians was popularized in the late Soviet era by the novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.5

Today, Putin openly claims that Ukrainians and Russians are “one people” whose political fates should remain entwined irrespective of Ukraine’s distinct history—as well as the clear preference of most Ukrainians to remain free of Russian domination.6 This outlook also has the backing of the Russian Orthodox Church, which regards the East Slavic, Orthodox-majority realm as its own “canonical territory,” rejecting efforts to build an autocephalous Ukrainian Orthodox Church.7

While its troops are rampaging across eastern Ukraine, Putin’s Russia has also established political dominion over neighboring Belarus, where the emergence of a distinct national identity is less developed than in Ukraine, and where authoritarian leader Aleksandr Lukashenko has accepted subordination to Moscow as the price for remaining in power following a large-scale uprising against his rule in 2020. Belarus has been incorporated into Russian military planning. Large numbers of Russian troops and security forces (including from the Wagner Group responsible for an abortive June 2023 insurrection against the Russian high command)—and now, nuclear weapons—are based on Belarusian territory. Leaked Kremlin documents suggest that Russia aims to effectively annex Belarus by 2030.8

Russia also maintains a small contingent of troops in Transnistria, which lies mainly on the east bank of the Dniester River bordering Ukraine. In the initial stages of the war, Russia attempted to capture the Ukrainian port city of Odesa, which would have allowed it to forge a land link to Transnistria, and Russia continues using its presence in Transnistria to destabilize Moldova.9 Moscow is also particularly interested in Kazakhstan—especially the provinces along the Russian border—because of the country’s large ethnic Russian presence (currently around 15% of the population, down from 37% at the time of the Soviet collapse).10 Though Kazakhstan has joined all of Russia’s multilateral integration initiatives and prioritizes close relations with its larger neighbor, it faces continual pressure. In 2014, Putin questioned the historical legitimacy of Kazakh statehood, a theme to which officials and nationalist commentators still return.11

Inner Core and Outer Rim

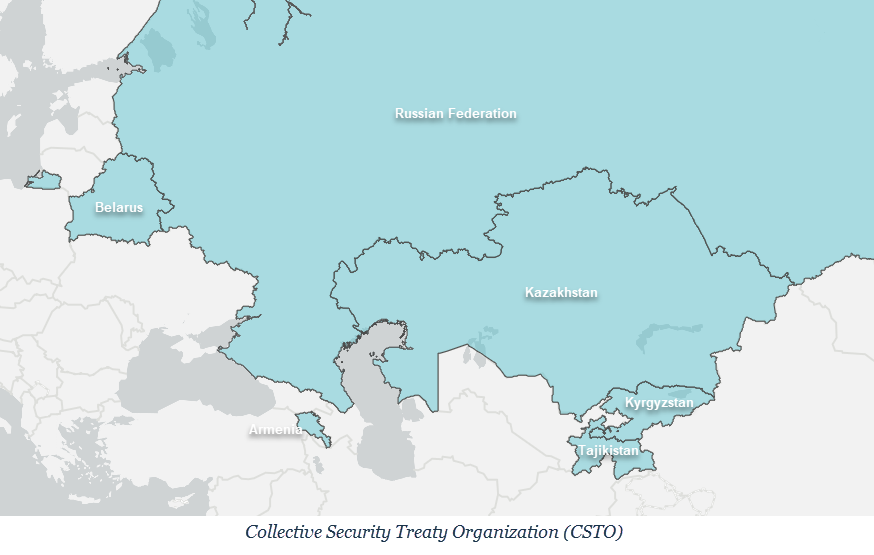

Belarus and Kazakhstan—along with Armenia and Kyrgyzstan—constitute an inner core of post-Soviet states that remain tied to Russia through the EEU and CSTO, both set up to embed Russia’s regional influence in multilateral frameworks. Nominally analogous to the European Union and NATO, respectively, the EEU and CSTO constrain the ability of their smaller members to seek Euro-Atlantic integration, while reinforcing the idea of a Russo-centric Eurasia as what Putin termed “one of the poles in the modern world and…a bridge between Europe and the dynamic Asia-Pacific region.”12

The EEU centers on a customs union that has bolstered trade among members (especially between smaller members and Russia), while forcing many of the smaller states to impose new barriers to trade with nonmembers. Despite rules designed to promote consensus, in practice Moscow dominates decision-making within the EEU and has reaped most of the economic gains.13

The CSTO, in theory, obligates members to provide one another with assistance in case of a threat to their security. It also offers a framework for Moscow to deploy troops, organize military exercises, dominate markets for weapons, and legitimize a regime-centric perspective on security that reinforces authoritarian rule.

Russia uses both organizations to discourage its neighbors from seeking integration with Euro-Atlantic institutions. The conflict in Ukraine initially broke out because of Russian attempts to pull Kyiv into the EEU and prevent it from signing an association agreement with the European Union. CSTO members, meanwhile, must receive assent from other member states before hosting foreign military assets.14

Though Russian influence in the outer rim of states beyond the EEU and CSTO is contested by rivals such as China, the European Union, and Turkey, Moscow remains a key powerbroker. It manipulates protracted or “frozen” conflicts on the territory of Moldova and Georgia that have complicated both states’ efforts to achieve Euro-Atlantic integration. Russia has also been the main outside actor seeking to regulate the conflict between CSTO member Armenia and nonmember Azerbaijan, and the main security partner for neutral Turkmenistan. Moscow tolerates a higher degree of independence among such states far from its borders, as long as these states do not harbor transnational terrorist groups or drug traffickers who threaten Russian interests—or cooperate too closely with the United States.

To Greater Eurasia—and Beyond

While Moscow has prioritized efforts to maintain political, cultural, and economic influence within the post-Soviet region, the idea of Eurasia as a political and moral counterweight to the West also influences Russia’s interactions with a wider set of states on the Eurasian landmass. Thinkers from the so-called Neo-Eurasianist school—most prominently Aleksandr Dugin—emphasize the idea that the peoples of Eurasia bear a distinct philosophical and even biological essence that predetermines them to prioritize the collective over the individual and to seek a strong leader who can organize them for a Darwinian struggle against a supposedly decadent West.15 The influence of such thinkers on Russian decision-makers is much debated. At a minimum, Dugin and his ilk have been strong proponents not just of the war in Ukraine but of the Kremlin’s somewhat amorphous pursuit of the Greater Eurasian Partnership that extends beyond the borders of the former Soviet Union.16

Putin officially embraced this Greater Eurasia concept at the 2016 St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, praising the “great potential for cooperation between the [EEU] and other countries and integration projects,” including China, India, Iran, Pakistan, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.17 In attempting to extend the idea of Eurasia beyond the frontiers of the old Soviet Union, the Greater Eurasia concept attempts to compensate for Russia’s relative weakness by bandwagonning with China, India, and others. The concept has struggled to gain traction beyond Russia, with just a handful of minor trade deals to its name. Yet Moscow continues to emphasize it in public messaging, as exemplified by the signing of a declaration on a Sino-Russian friendship “with no limits” a few weeks before Russian forces poured into Ukraine in February 2022.18

Building or Breaking an Empire

These overlapping initiatives suggest the extent to which the frontiers of the Kremlin’s mental map remain fluid. The actual degree of Russian influence or control is far from uniform, even within each circle: much as the Kremlin regards Ukraine as an inalienable part of Russia’s patrimony, the resistance of ordinary Ukrainians to Russia’s brutal war suggests a significant misreading of facts on the ground.

The war’s echoes are also felt far beyond Ukraine. The EEU and CSTO have both come under enormous strain since Russia’s full-scale invasion: leaders of the other member states do not want to be dragged into Russia’s war, or to be collateral damage in the West’s race to impose sanctions. Amid flaring tensions with their neighbors, both Armenia and Kyrgyzstan have criticized the failure of the CSTO (i.e., Russia) to fulfill its collective security obligations and have taken steps to distance themselves from the organization.19 Regardless of how the war in Ukraine ends, both the EEU and CSTO are likely to come out of it much weakened.

The erosion of Russian power and influence in much of the former Soviet Union has been a gradual process, facilitated by the rise of the first truly post-Soviet generation in politics, education, and culture. Intervention in neighboring states’ politics and the construction of Russian-led multilateral institutions have at most slowed that process. Russia’s biggest failure has been in Ukraine, which decisively turned its back on Russian-led integration in 2013–14. The invasion of Ukraine looks, therefore, like a desperate attempt to turn back the clock. It is unlikely to succeed—and may well end up accelerating the very erosion of Russian influence that it was designed to check, not just in Ukraine but across Moscow’s claimed sphere of “privileged interests.”

Jeffrey Mankoff is a Distinguished Research Fellow at National Defense University’s Institute for National Strategic Studies.

NOTE: The views expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not represent an official policy or position of the National Defense University or the U.S. Department of Defense.

Image Credits

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research

Maps ©The National Bureau of Asian Research

ENDNOTES

- Dmitry Medvedev, “Interv’yu Dmitriya Medvedeva rossiyskim telekanalam” [Dmitry Medvedev’s Interview to Russian TV Channels], Kremlin, August 31, 2008, http://www.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/1276.

- Gerard Toal, Near Abroad: Putin, the West, and the Contest over Ukraine and the Caucasus (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 3.

- Tajikistan is a member of the CSTO but not the EEU. Uzbekistan was formerly a member of the CSTO and the EEU’s precursor but withdrew from both organizations.

- Marlene Laruelle, “The ‘Russian World’: Russia’s Soft Power and Geopolitical Imagination,” PONARS Eurasia, May 27, 2015, https://www.ponarseurasia.org/the-russian-world-russia-s-soft-power-and-geopolitical-imagination.

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Rebuilding Russia: Reflections and Tentative Proposals, trans. Alexis Klimoff (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1991).

- Vladimir Putin, “Stat’ya Vladimira Putina ob istoricheskom yedinstve russkikh i ukraintsev” [Article by Vladimir Putin on the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians], Kremlin, July 21, 2021, http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181. For context, see Jeffrey Mankoff, “Russia’s War in Ukraine: Identity, History, and Conflict,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 22, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russias-war-ukraine-identity-history-and-conflict.

- On the Russian Orthodox Church’s conception of its “canonical territory,” see M.D. Suslov, “‘Holy Rus’: The Geopolitical Imagination in the Contemporary Russian Orthodox Church,” Russian Politics and Law 52, no. 3 (2014): 18–21; and Johannes Oeldemann, “The Concept of Canonical Territory in the Russian Orthodox Church,” in Religion and the Conceptual Boundary in Central and Eastern Europe, ed. Thomas Bremer (London: Palgrave, 2008), 229–36.

- Amy Mackinnon, “Belarus Is the Other Loser in Putin’s War,” Foreign Policy, May 4, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/05/04/belarus-ukraine-russia-war-putin; and Michael Weiss and Holger Roonemaa, “Revealed: Leaked Document Shows How Russia Plans to Take Over Belarus,” Yahoo News, February 20, 2023, https://news.yahoo.com/russia-belarus-strategy-document-230035184.html.

- Maximilian Popp, “Putin Seeks to Destabilize Ukraine’s Neighbor,” Der Spiegel, November 23, 2022, https://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/russia-s-second-front-putin-seeks-to-destabilize-ukraine-s-neighbor-a-ea3305a2-61a7-4ffe-8f57-9d8231abc434.

- Farangis Najibullah, “Ethnic Balancing? Kazakhstan Settles Returnees in Regions with Significant Russian-Speaking Populations,” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty (RFE/RL), November 9, 2022, https://www.rferl.org/a/kazakh-settles-returnees-russian-speaking-regions/32122862.html.

- Farangis Najibullah, “Putin Downplays Kazakh Independence, Sparks Angry Reaction,” RFE/RL, September 3, 2014, https://www.rferl.org/a/kazakhstan-putin-history-reaction-nation/26565141.html; and Paolo Sorello, “Former Russian President Questions Kazakhstan’s Sovereignty,” Diplomat, August 5, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/former-russian-president-questions-kazakhstans-sovereignty.

- Vladimir Putin, “Novyy integratsionnyy proyekt dlya Yevrazii—budushchee, kotoroe rozhdayetsya segodnya” [A New Integration Project for Eurasia––the Future that is Born Today], Izvestiya, October 3, 2011, https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/novyy-integratsionnyy-proekt-dlya-evrazii-buduschee-kotoroe-rozhdaetsya-segodnya.

- Irina Busygina, “Russia in the Eurasian Economic Union: Lack of Trust Limits the Possible,” PONARS Eurasia, Policy Memo, February 2019, 571, http://www.ponarseurasia.org/memo/russia-eurasian-economic-union-lack-trust-russia-limits-possible; and Rilka Dragneva and Kataryna Wolczuk, “The Eurasian Economic Union: Deals, Rules and the Exercise of Power,” Chatham House, May 2017, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2017-05-02-eurasian-economic-union-dragneva-wolczuk.pdf.

- “Ustav Organizatsii dogovora o kollektivnoi bezopasnosti” [Charter of the Collective Security Organization], CSTO, April 26, 2012, https://www.odkb-csto.org/documents/documents/ustav_organizatsii_dogovora_o_kollektivnoy_bezopasnosti.

- See, among, others Marlene Laruelle, “Aleksandr Dugin: A Russian Version of the Radical Right?” Wilson Center, Occasional Paper, no. 294, 2006, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/OP294_aleksandr_drugin_laruelle_2006.pdf; and Edith W. Clowes, “Postmodernist Empire Meets Holy Rus’: How Aleksandr Dugin Tried to Change the Eurasian Periphery into the Sacred Center of the World,” in Russia on the Edge: Imagined Geographies and Post-Soviet Identity (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011), 43–67.

- Timothy Snyder, The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America (New York: Crown, 2018), 88–109; Aleksandr Rybakov, “Svoya stikhiya: Sergey Glaz’yev—o yevraziyskom integratsii” [Its Own Element: Sergey Glazyev—on Eurasian Integration], Ritm Yevrazii, September 12, 2019, https://www.ritmeurasia.org/news--2019-09-12--svoja-stihija-sergej-glazev-o-evrazijskoj-integracii-44812; and Andrei Kolesnikov, “History Is the Future: Russia in Search of the Lost Empire,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 15, 2018, https://carnegiemoscow.org/commentary/75544.

- Vladimir Putin, “Plenarnoe zasedanie Peterburgskogo mezhdunarodnogo ekonomicheskogo foruma” [Plenary Session of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum], Kremlin, June 17, 2016, http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/52178.

- “Sovmestnoe zayavlenie Rossiiskoi Federatsii i Kitaiskoi Narodnoi Respubliki o mezhdunarodnykh otnosheniyakh, vstupayushchikh v novuyu epokhu, i global’nom ustoichivom razvitii” [Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on International Relations Entering a New Era and Global Sustainable Development], Kremlin, February 4, 2022, http://kremlin.ru/supplement/5770.

- “Armenian PM Did Not Sign CSTO Security Council’s Declaration Draft on Aid to Armenia,” TASS Russian News Agency, November 30, 2022, https://tass.com/world/1541151; and “Kyrgyzstan Cancels Planned CSTO Exercises,” RFE/RL, October 9, 2022, https://www.rferl.org/a/kyrgyzstan-cancels-csto-military-exercises-belarus-russia/32072105.html.