The digital architecture of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is an expanding strategic space. As both an imagined and physical space, the Digital Silk Road will create opportunities and risks for national security, data, and privacy globally. Concurrent with the Digital Silk Road, the PRC is expanding its presence in the maritime and undersea domains through oceanographic surveillance and the exploration of deep-sea mining. Unlike territorial conceptions of strategic space, the digital and undersea domains are not as clearly delineated.

This essay examines China’s conceptualization of its strategic space in these domains and how the digital undersea relates to the PRC party-state’s long-term strategic goals. This essay focuses on two main questions. First, what is the PRC’s strategy for its global digital architecture? Second, how do those digital goals intersect with the undersea domain? After summarizing the PRC’s maritime and digital goals, I focus on three areas of overlap: submarine fiber-optic cables, the mapping of the subsea floor, and deep-sea mining. The conclusion draws out a subset of the implications of China’s expanding strategic space in the digital undersea.

Maritime and Digital Goals: Crossover in the Undersea

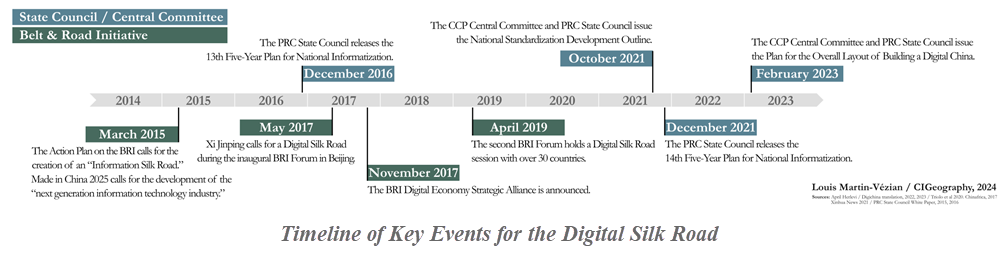

China’s maritime strategy has evolved significantly over the past several decades. The PRC is developing the maritime economy, and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is “enacting the ‘strategic requirements of near seas defense, far seas protection.’”1 The focus thus far for PRC civilian and military actors has primarily been surface exploration, protection of the first island chain (in part, via establishment of permanent facilities in the South China Sea), and expansion of the PRC’s maritime presence in the Indian Ocean and beyond. However, state actors are also increasingly assessing the “deep-sea” (shenhai) and “subsea” (haidi) domains.2 “China’s Ocean Agenda for the 21st Century,” released in 2009 by the PRC National People’s Congress, noted that “future marine industries” include ocean energy utilization, deep-sea mining, and the “marine information industry” (haiyang xinxi chanye). The 14th Five-Year Plan, which covers the period from 2021 to 2025, reiterated these areas and included “deep-sea engineering” as part of “cutting-edge technologies” that should be pursued in the next decade. The PRC’s Digital Silk Road was first anointed in 2015, but many of the projects that are now linked to it had already begun under the purview of national “informatization” and “digital China.” In the 13th Five-Year Plan, which covered the period from 2016 to 2020, the intersection between maritime strategy and digital goals took shape more clearly with the PRC expanding the “projects” that would be considered part of “safeguarding maritime rights and interests,” including marine exploration and global ocean observation. In the 14th Five-Year Plan an entire chapter was devoted to digital China further expressing the country’s desire to “strengthen the innovative application of key digital technologies,” including “high-end chips, operating systems, key AI algorithms, sensors, etc.” During a speech at the inaugural Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Forum, Chairman Xi Jinping argued that to “persist in innovation-driven development,” China must advance in fields as diverse as the “digital economy, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, and quantum computers, promote the construction of big data, cloud computing, and smart cities,” and build the connections that link these systems.3

To narrow the scope, I cross-referenced three overlapping areas: PRC maritime strategy, digital goals, and the deep-sea domain. Among these, there are at least three key dimensions that represent an expanding strategic space for the PRC. First, undersea fiber-optic cables represent the telecommunications connectivity that is the basis for portions of the Digital Silk Road.4 Second, to lay cables or conduct ocean research, companies or governments must map the seabed floor. Third, global telecommunications networks require critical minerals as inputs for the digital architecture, and thus deep-sea mining of those minerals is becoming more economically (and technologically) viable.

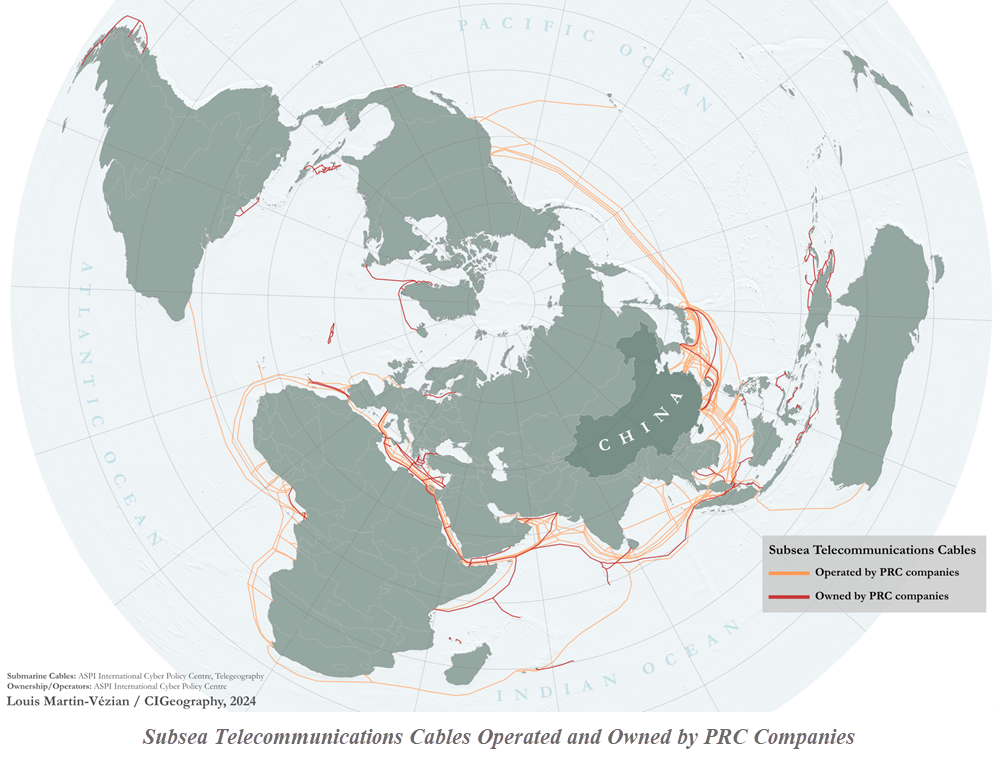

Telecommunications in the Undersea

The PRC’s plans for the Digital Silk Road describe “facilities connectivity” as critical to the “infrastructure construction plans and technical standard systems…[necessary] to form an infrastructure network connecting all subregions in Asia, and between Asia, Europe, and Africa.”5 The BRI Action Plan also states that China “should jointly advance the construction of cross-border optical cables and other communications trunk line networks, improve international communications connectivity, and create an Information Silk Road.” It adds that China “should build bilateral cross-border optical cable networks at a quicker pace, plan transcontinental submarine optical cable projects, and improve spatial (satellite) information passageways to expand information exchanges and cooperation.”6 According to AidData, there are over 500 communications-related projects that the PRC has financed between 2000 and 2017.7 Most of these projects preceded the branding strategy now associated with the Digital Silk Road, but those projects laid the groundwork for greater digital connectivity.8 Despite the volume of PRC digital projects, in terms of undersea telecommunications links, PRC firms are not yet dominant. According to TeleGeography (an industry consultancy) and analysis by the Financial Times, Chinese supplier HMN Technologies (the rebranded Huawei Marine Networks) “provided or is set to provide the equipment to only 10 percent of all existing and planned global cables, where the supplier is known.”9 Yet this figure could be a low estimate. HMN Tech’s promotional materials state that the company is involved in “over 100 cable projects in 70 countries,” but it is unclear how many of those projects are subsea cables rather than terrestrial ones. Of the undersea cable projects with PRC involvement (and where ownership can be identified), Huawei was involved in approximately 45%.10 The other 55% of PRC subsea cable projects were split among China Unicom, China Telecom, and China Mobile.11

The Mapping of the Undersea Domain

“China’s Ocean Agenda for the 21st Century” noted the country’s need to develop ocean observation technologies, remote-sensing and digital programs, and enhanced computer-enabled data processing. According to one academic analysis outlining the history of the Digital Ocean project, the idea was proposed in 1999, and in 2003 the program to “comprehensively survey offshore oceans” was launched with funding from the 908 special project.12 In the 13th Five-Year Plan, the PRC government called for the realization of this “multi-dimensional global ocean observation network.” The goals for this overall ocean-monitoring network were later reiterated in the 14th Five-Year Plan including “real-time online monitoring systems and overseas observation (monitoring) stations for the marine environment” to “strengthen observation and research on marine ecosystems, ocean currents, and maritime meteorology.” While these marine monitoring systems might concentrate on environmental, meteorological, and related scientific research, basic bathymetry is necessary to lay submarine cables and conduct deep-sea mining.

Deep-Sea Mining

As global demand for critical minerals increases, companies and countries looking for new sources will begin mining the deep-sea floor. According to experts at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Global Marine Mineral Resources project, “commercial deep-ocean mining will be underway within half a decade.” Companies are exploring the “concentration of such metals as copper, zinc, gold, and silver,” along with interest in manganese nodules that might include nickel, copper, cobalt, and lithium.13 An article published in the PRC journal Strategy and Policy emphasizes the importance of critical minerals on the seabed floor in the Pacific Islands, noting that the region likely has robust deposits for polymetallic manganese nodules and cobalt manganese crusts, among other potential metals.14 The article then describes how “strengthening the development of deep-sea resources is one step to enhancing maritime governance” and pursuing “South Pacific maritime resource cooperation” will help expand the “marine space of China.”15

Expanding deep-sea “marine space” will generate debates among nation-states, governments, and international organizations. Who owns seabed resources in oceans beyond national jurisdiction? Who controls access to the data generated in mapping the seabed floor?16 The United Nations has declared 2021–30 the “Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development,” with the goal to “coordinate the mapping of all the world’s oceans.”17 Generating and sharing this data will likely promote scientific research and the utilization of seabed resources, but it will also create controversies. In 2021 the Pacific Island country of Nauru informed the International Seabed Authority (ISA) of its interest in exploring deep-sea mining in its exclusive economic zone (EEZ), and this notification required the ISA to finalize governing rules for the industry.18 Those rules should have already been promulgated,19 but in July 2023 a subset of Pacific Island countries called for a moratorium on mining to allow more time for research on the environmental implications.20

Implications of the Digital Undersea

The expansion of the Digital Silk Road globally has implications for connectivity and access to communications networks, control of data and deep-sea mineral resources, and environmental protection. For each realm discussed in this essay—undersea telecommunications cables, the mapping of the seabed floor, and deep-sea mining—exploration and expansion raise important questions about security, resilience, ownership, and the rules of the road. This section considers a subset of those implications as a starting point for future conversations globally.

For telecommunications connectivity, there are concerns about disruptions (intentional or natural) and the reliability of access to data and networks for citizens, organizations, and governments. Two recent incidents reinforce some of these concerns. In February 2023, several submarine cables that connect Taiwan and its outer island of Matsu were severed—one by the hook of a cargo ship and the other by a Chinese fishing vessel.21 The vessels in question asserted that the breach was accidental, but Taiwan news organizations reported that illegal sand dredging has become common around Matsu and may be contributing to these accidents.22 Regardless of the cause, internet connectivity for Matsu was disrupted, affecting medical services, financial transactions, transportation, and communications. In October 2023, a second cable disruption occurred, this time outside China’s maritime periphery. On October 8, seismic activity was detected in the Baltic Sea, and government authorities later confirmed that “damage to an undersea gas pipeline and telecom cable between Finland and Estonia” had occurred.23 Finnish authorities named the Hong Kong–flagged and Chinese-owned ship MV Polar Bear as the likely cause, and authorities have questioned whether the anchor drag that damaged the pipeline was accidental.24

To ensure the resilience of digital networks for their citizens, national governments may need to revisit their role in networks that are primarily owned and operated by private corporations.25 While incidents like those near Taiwan’s outer islands and in the Baltic Sea are of concern,26 disruptions to undersea cables can also occur due to natural disasters. In 2022 the international undersea cable connecting the Pacific Island of Tonga broke due to the eruption of the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai volcano. The repair to the international cable, which connects to Fiji, took slightly over a month because of multiple breaks along the Tonga cable.27 Repairs to the domestic cable took even longer and reflect the limited capacity for repairs worldwide. In sub-Saharan Africa, there is only one fiber-optic submarine cable repair ship currently in operation, the Leon Thevenin, owned by Orange Marine. The Leon Thevenin has been in use for over 40 years, making it the second-oldest cable repair ship.28

Efforts to map the seabed floor are not new for the PRC, but there are a host of environmental and security concerns. In 2015, China State Shipbuilding Corporation, a PRC state-owned enterprise, announced plans to build a network of undersea sensors in the South China Sea.29 The system, referred to as the “underwater Great Wall,” could be used for oceanographic research, environmental monitoring, tactical surveillance, and surveying of the seabed floor.30 The use of underwater data sensors has implications for security, economics, and climate change, as well as the nexus between these issues. To address decarbonization goals, countries need to reduce the energy footprint of data centers.31 Thus, placing energy-intensive systems underwater could make sense for cooling. As undersea digital infrastructure is expanded, questions about how to ensure safety and security become more complicated.

International organizations, such as the United Nations General Assembly, and regional organizations, such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), have stated that undersea cables are “critical infrastructure.”32 But who is responsible for protection of this critical infrastructure in the global commons? A data center within the twelve nautical mile limit would fall under the jurisdiction of that nation, according to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, but what about data centers in international waters? Does a data center in an EEZ need unique protections, and, if so, how are those protections provided? What about the many overlapping and contested EEZs that exist in the Asia-Pacific? How do countries decide where to place this type of infrastructure, and what are the rules and norms for ensuring safety and security?

For deep-sea mining, many of the same debates on rules are emerging.33 Nation-states with large EEZs must think about how to manage seabed resources, recognizing that the seabed is becoming a site of competition.34 Deep-sea mining is not yet widespread, but as U.S.-China technology competition leads to more instances of countries trying to control or access critical minerals, seabed mining could look increasingly attractive. In July 2023, China passed a series of export controls on gallium and germanium.35 In August, China did not export these two critical minerals—both of which are used in a wide variety of applications, including semiconductors, transistors, and other small electronic devices.36 The expansion of digital connectivity through undersea cables, the mapping of the seabed floor, and mining for critical mineral deposits are each likely to be facets of international relations over the next decade. The PRC has promulgated its plans via the Digital Silk Road, but as technology evolves, new strategic spaces are opening. Digital plans will increasingly include the undersea domain as the use of underwater data centers and related technologies comes to fruition. Digital and undersea expansion will increase China’s strategic space. Yet, for other countries, the environmental and monetary implications of this trend could impede on their own strategic space. As competition intensifies, we need to ask hard questions about access, control, resiliency, and management so that citizens and countries can make effective choices about how the digital undersea future evolves.

April A. Herlevi is a Nonresident Fellow at the National Bureau of Asian Research.

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

Timeline of Key Events for the Digital Silk Road | Louis Martin-Vezian / CIGeography, 2024; April Herlevi; Digichina translation, 2022, 2023; Triolo et al. 2020. Chinafrica, 2017; Xinhua News 2021; RPC State Council While Paper, 2015, 2016.

Subsea Telecommunications Cables Operated and Owned by PRC Companies | Louis Martin-Vezian / CIGeography, 2024; Submarine Cables: ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre, Telegeography; Ownership/Operators: ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre.

ENDNOTES

- April A. Herlevi and Christopher Cairns, “China’s Activities in the Pacific Island Countries: Laying the Foundations for Future Access in Oceania?” in Enabling a More Externally Focused and Operational PLA, ed. Roger Cliff and Roy D. Kamphausen (Carlisle: U.S. Army War College Press, 2022), 111.

- In English, these terms are translated as subsea, undersea, submarine, or deep-sea. While there are slight differences between subsea and deep-sea in the Chinese context, here we use these terms interchangeably.

- Xinhua, “Xi Jinping zai ‘yi dai yi lu’ guoji hezuo gaofeng luntan kai mu shi shang de yanjiang” [Speech by Xi Jinping at Belt and Road International Cooperation Summit and Forum Opening Ceremony], Xinhua, May 14, 2017, http://www.xinhuanet.com/world/2017-05/14/c_1120969677.htm.

- Analysis of undersea telecommunications cables and potential risks to those networks represents an important growing area of scholarly and policy research. See, for example, Camino Kavanagh, “Wading Murky Waters: Subsea Communications Cables and Responsible State Behavior,” UN Institute for Disarmament Research, 2023; Tara Davenport, “Intentional Damage to Submarine Cable Systems by States,” Hoover Institution, Aegis Series Paper, no. 2305, October 26, 2023; and Elsa B. Kania, “Enhancing the Resilience of Undersea Cables in the Indo-Pacific,” S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, RSIS Commentary, August 21, 2023.

- National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), “Action Plan on the Belt and Road Initiative,” March 2015, http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/publications/2015/03/30/content_281475080249035.htm.

- Ibid., 5.

- Samantha Custer, “Tracking Chinese Development Finance: An Application of AidData’s TUFF 2.0 Methodology,” AidData, William and Mary, September 2021, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/aiddata-tuff-methodology-version-2-0.

- Firms such as Huawei, China Unicom, China Telecom, China Mobile, and HMN Technologies have all been involved in telecommunications sector projects.

- Anna Gross et al., “How the U.S. Is Pushing China Out of the Internet’s Plumbing,” Financial Times, June 12, 2023, https://ig.ft.com/subsea-cables. According to the Financial Times analysis, French company ASN supplies 41% of equipment and U.S. firm SubCom supplies about 21% of global supplies.

- Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), “Mapping China’s Tech Giants,” 2021, https://chinatechmap.aspi.org.au. Author’s analysis of ASPI data downloaded in December 2022.

- Ibid.

- Li Sihai, Jiang Xiaoyi, and Zhang Feng, “Wo guo shuzi haiyang jianshe jinzhan yu zhanwang” [Our Country’s Digital Ocean Construction Progress and Forecast], Ocean Development and Management, June 2010, http://www.haiyangkaifayuguanli.com/hykfygl/ch/reader/view_abstract.aspx?file_no=100613&flag=1.

- U.S. Geological Survey, Coastal and Marine Hazards and Resources Program, “How Will Underwater Mining Affect the Deep Ocean? Growing a Research Community to Find Out,” May 31, 2018, https://www.usgs.gov/news/how-will-underwater-mining-affect-deep-ocean-growing-research-community-find-out.

- Liang Jia-Rui, “Zhongguo-Dayangzhou-Nantai pingyang lanse jingji tongdao goujian: jichu, kunjing, and gouxiang” [China-Oceania-South Pacific Blue Economic Passage Construction: Foundation, Dilemma, and Conception], Zhanlüe yu juece 3 (2018).

- Ibid.

- “Undersea Cables, Geoeconomics, and Security in the Indo-Pacific: Risks and Resilience” (conference convened by the Center for Indo-Pacific Affairs at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, October 26–27, 2023). The International Seabed Authority, the International Telecommunication Union, the International Hydrographic Organization, and other international organizations could all play a role in distinct aspects of these issues over the next decade.

- “Seabed 2023,” Nippon Foundation and General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans, https://seabed2030.org/about.

- Helen Reid, “Pacific Island of Nauru Sets Two-Year Deadline for UN Deep-Sea Mining Rules,” Reuters, June 29, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/pacific-island-nauru-sets-two-year-deadline-deep-sea-mining-rules-2021-06-29.

- “ISA Assembly Concludes Twenty-Eighth Session with Participation of Heads of States and Governments and High-Level Representatives and Adoption of Decisions on the Establishment of the Interim Director General of the Enterprise,” ISA, Press Release, August 2, 2023, https://www.isa.org.jm/news/isa-assembly-concludes-twenty-eighth-session-with-participation-of-heads-of-states-and-governments-and-high-level-representatives-and-adoption-of-decisions-on-the-establishment-of-the-interim-director.

- Stephen Wright, “Deep-Sea Mining Tussle Highlights Divide among Pacific Island Nations,” Radio Free Asia, July 20, 2023, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/environment/pacific-deep-sea-mining-07202023003741.html.

- Yau-Chin Tsai, “The Influence of Matsu Undersea Cable Interruption on Taiwan’s National Defense Security,” Institute for National Defense Security Research, Newsletter, July 28, 2023.

- Ibid.

- “Seismic Signal Detected in Vicinity of Gas Pipelines in the Eastern Baltic Sea,” NORSAR, October 10, 2023; and “The Damage to a Baltic Undersea Cable Was ‘Purposeful,’ Swedish Leader Says but Gives No Details,” Associated Press, October 24, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/sweden-estonia-damage-cable-finland-telecoms-pipeline-19c7f951b833b709cdf5f74b9a2dd221.

- Andrius Sytas, “Estonia Focuses on Chinese Vessel in Investigation into Underwater Cable Damage,” Reuters, October 25, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/estonia-focuses-chinese-vessel-investigation-into-underwater-cable-damage-2023-10-25. The author thanks Chris Kremidas-Courtney, a senior fellow at Friends of Europe (a Brussels-based think tank), for sharing this news report.

- Kavanagh, "Wading Murky Waters".

- For more on the legal issues surrounding intentional disruptions, see Davenport, “Intentional Damage to Submarine Cable Systems.”

- Dan Swinhoe, “Tonga’s International Subsea Cable Repaired after Volcanic Eruption,” Data Centre Dynamics, February 22, 2022, https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/news/tongas-international-subsea-cable-repaired-after-volcanic-eruption.

- Jess Auerbach Jahajeeah, “Down to the Wire: The Ship Fixing Our Internet,” Continent, November 25, 2023, 11–15. Orange Marine was formerly France Telecom Marine and specializes in laying and maintaining undersea cables. See Orange Marine, “Who We Are,” https://marine.orange.com/en/who-we-are.

- Catherine Wong, “‘Underwater Great Wall’: Chinese Firm Proposes Building Network of Submarine Detectors to Boost Nation’s Defence,” South China Morning Post, May 19, 2016, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/1947212/underwater-great-wall-chinese-firm-proposes-building.

- Dolma Tsering, “China’s ‘Undersea Great Wall’ Project: Implications,” National Maritime Foundation, December 9, 2016, https://maritimeindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/CHINA-UNDERSEA-GREAT-WALL-PROJECT-IMPLICATIONS.pdf.

- Yujie Xue, “Climate Change: China’s Data Centres and Telecoms Networks in Beijing’s Sights as Key Targets for Decarbonisation,” South China Morning Post, October 13, 2022, https://www.scmp.com/business/article/3195779/climate-change-chinas-data-centres-and-telecoms-networks-beijings-sights.

- Davenport, “Intentional Damage to Submarine Cable Systems,” 1; and Mark Bryan Manantan, “The ASEAN-Quad Partnership in Undersea Cables: Building Inclusion, Sustainability, and Regional Connectivity,” Australian National University, October 2023, https://nsc.crawford.anu.edu.au/publication/21533/asean-quad-partnership-undersea-cables-building-inclusion-sustainability-and.

- Isaac Kardon and Sarah Camacho, “Why China, Not the United States, Is Making the Rules for Deep-Sea Mining,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, December 19, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/12/19/why-china-not-united-states-is-making-rules-for-deep-sea-mining-pub-91298.

- Recent debates about deep-sea mining have even prompted new documentary films, such as Deep Rising.

- “PRC Imposes Critical Mineral Restrictions,” CNA, Intersections, October 2023, https://www.cna.org/our-media/newsletters/intersections/issue-6.

- Amy Lv and Dominique Patton, “China Exported No Germanium, Gallium in August after Export Curbs,” Reuters, September 20, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-exported-no-germanium-gallium-aug-due-export-curbs-2023-09-20.