In October 2014 the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) held its 17th International Symposium Course, which was attended by 48 international representatives in Beijing, including the author.1 At this conference, PLA officers employed the Chinese concept “strategic space” in reference to their perceived strategic disadvantage, which they blamed on their containment within the “first island chain.” They sought to rectify the position of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) with the possession of Hong Kong, the South China Sea, and Taiwan and through “counter-encirclement” by projecting power beyond the “second island chain.”2 Parallels were drawn between contemporary challenges to Russian and Chinese strategic space involving “color revolutions” (Kyiv’s Euromaidan protests and Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement), and sympathy was expressed for Russia’s need to annex Crimea for “the strategic space it needed to survive.”3

However, PRC diplomats awkwardly clung to the narrative of “peaceful rise,” denounced hegemony and proclaimed noninterference.”4 One strategist pledged China would “never” have bases overseas, a claim previously made by PRC defense white papers.5 This narrative reinforced academic arguments that the Pacific Islands were a “low strategic priority” or residing on the “greater periphery” of China’s grand strategy.6 Others argued the Pacific Islands were of no strategic interest to China at all,7 an idea supported by Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare of Solomon Islands in 2023.8

The PRC has openly signaled its interest in the Pacific as a strategic space for almost two decades. As early as 2001, a Chinese strategist suggested that China should “get actively involved” in the national affairs of the islands of the “fragmented zone,” including Solomon Islands, “and vigorously cultivate pro-China forces.”9 Premier Wen Jiabao then declared that China’s engagement with the Pacific Islands was a “strategic decision” during his 2006 address to Pacific Island countries in Suva. President Xi Jinping’s visits to Suva in 2014 and Port Moresby in 2018 were unprecedented in their signaling and influence. Xi, having already visited Fiji as vice president in 2009, invited the Pacific Islands to “take a ride on the Chinese ‘express train’ of development” when he offered them more development assistance in 2014.10 In 2017 the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) belatedly linked China to the South Pacific with the “blue economic passage,” and in the following year Xi shaped the geopolitical environment of the Pacific when he visited Papua New Guinea (PNG) for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit. He secured the membership of all eligible Pacific Islands in his new BRI, influencing Solomon Islands and Kiribati to switch diplomatic recognition to Beijing in 2019.

These were the opening moves of China’s quest for strategic space in the Pacific. This intent was further clarified by the signing of a security agreement with Solomon Islands, followed by the proposal of a “common development vision” before Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s tour of the Pacific Islands in mid-2022.11 The proposal sought to align China’s political, economic, and security cooperation with ten Pacific Islands through multilateral initiatives that would compete with existing regional architectures.12 While recent moves may have focused strategic attention on Solomon Islands, the PRC continues to work quietly on its influence and access in countries such as PNG, Fiji, Vanuatu, Samoa, and Kiribati. These efforts demonstrate that the Pacific Islands are of greater priority in China’s grand strategy than many believed.13 China has employed BRI as a geoeconomic strategy, a narrative, and a framework to deliver integrated political, economic, and security statecraft in the Pacific.14 This essay explains how and why the PRC has sought to expand its strategic space in the Pacific Islands since 2017. For simplicity, I present these developments as sequential stages, but their continued development is quite complex.

Political Statecraft

The first stage of building China’s geopolitical influence involved political statecraft—a combination of diplomacy, propaganda, and united front work. In 2017, Xi Jinping empowered the PRC’s ambassadors with control over the officials of other Chinese ministries and agencies working in-country.15 This gave them the authority to integrate statecraft and the responsibility for delivering China’s grand strategy on the ground with “one voice.” In the same year a new caliber of PRC diplomats began to arrive in the Pacific, which diplomats from other countries described as a “generational shift.”16 They were supported by increases in PRC propaganda and united front representation in-country. China’s new ambassadors to Melanesia and Timor-Leste had excellent English and a much stronger career profile. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) sent two experienced ambassadors to Melanesia in 2017—Xue Bing to Port Moresby and Qian Bo to Suva—and both were subsequently rewarded for their efforts with promotions. An indicator of the current ambassadorial cohort’s quality is that they have all been the deputy director-general of a department, normally of a central MFA Department.17

Unsurprisingly, each of these five countries joined BRI roughly a year after the arrival of its new PRC ambassador. Their membership, combined with the switch of recognition from Taipei to Beijing by Solomon Islands and Kiribati a year later, was a major geopolitical achievement of PRC political statecraft. These developments established the foundations for China’s grand strategy in the Pacific by expanding the country’s strategic space and reducing Taiwan’s.

Economic Statecraft

The second stage for achieving geopolitical influence focused on China’s economic statecraft, which had gradually been introduced with the arrival of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) over the previous two decades. The number of SOEs grew sharply with the signature of BRI memoranda of understanding with each Melanesian country. In PNG—the Pacific Island with the largest economy, population, and construction sector—major Chinese companies spiked from 21 to 39 in the year after the country joined BRI.18 With these numbers, PRC companies dominated Melanesian construction sectors and saturated the tender processes of multilateral banks such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and World Bank. Over 80% of the ADB’s infrastructure projects in PNG in 2019 were awarded to Chinese SOEs.19

This is a surprising finding, as the majority of the ADB’s funds come from countries that do not support BRI, such as Japan, India, the United States, and Australia. Yet the PRC is happy for these projects to be credited to the initiative.20 The trend of spending money from non-Chinese sources appears to have grown since there was a sudden decline in the PRC’s foreign reserves in 2016.21 The resultant preference for multilateral finance was demonstrated by China’s two lead BRI companies in Melanesia—China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) in PNG and China Civil Engineering Construction Company (CCECC) in Vanuatu. In 2019, 90% of CHEC’s and 75% of CCECC’s in-country projects were financed by multilaterals.22 Chinese companies compete for project tenders with bids that are 30%–50% below the “engineer’s price” and then further undercut each other by using subsidiaries to place extra bids, thus increasing their chances and giving the appearance of genuine competition.23 CCECC recently secured an AU$170 million ADB contract (which no other company tendered for) to rehabilitate the Honiara international port and build three others.24 SOE executives were also quite open about how they were required to prioritize the strategic goals of the party-state above profit and coordinated with the PRC’s in-country economic and commercial counselor from the Ministry of Commerce.25

Market dominance by economic statecraft is a key mode by which China achieves influence in a developing economy. This builds on the impact of other economic influence, such as hidden debt (international loans between SOEs rather than governments).26 The resulting geoeconomic traction can deliver the geopolitical influence and geostrategic access that are fundamental to securing China’s strategic space.

Security Statecraft

Stage three followed significantly later with the enhancement of security statecraft to take advantage of the opportunities and influence created by political and economic efforts, in search of geostrategic access. Since the PLA was first tasked by Hu Jintao to protect China’s national interests overseas in 2004, it had been directed to construct overseas bases, secure interests under BRI, and generate influence through security cooperation.27 In doing so, it was to cooperate closely with the PRC interagency to “create a favorable strategic posture” and “seize the strategic initiative in military competition.28 Until 2020, the PLA’s application of this guidance in the Pacific Islands had been very light security cooperation. While neighboring Timor-Leste had a PRC defense attaché from 2002 onward, there were none in the Pacific Islands. PLA attachés are trained in clandestine intelligence and can generate influence over strategic interests through continuous engagement with host-nation security forces, officials, and politicians. Their absence was cited as proof of the low strategic priority of the Pacific Islands.29

In October 2020, this situation changed when Senior Colonels Yu Ke and Zhang Xiaojiang arrived quietly in Suva and Port Moresby. By January 2022, the PRC had changed its security adviser footprint in the Pacific Islands from none to sixteen personnel in just over a year. After Senior Colonel Wang Wei was established in Nuku‘alofa in 2021, assistant defense attachés were added to the PRC embassies in Fiji, PNG, and Tonga. Supervisor Lu Lingzhen’s posting to Suva then established a precedent for “police liaison officers” to be used as quasi-attachés in Pacific countries with no military. The deployment of Commissioner Zhang Guangbao to Honiara with his “police liaison team” in January 2022 arguably demonstrated this concept.30 He appeared to manage PRC security statecraft and remained in place while the team rotated three times.

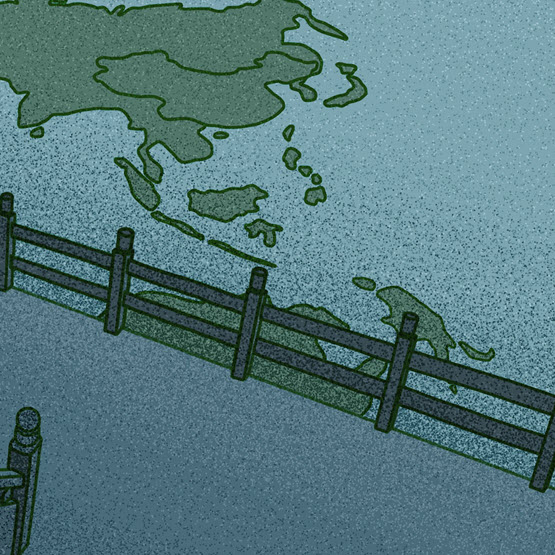

One objective for these security advisers is to secure geostrategic access and dual-use facilities to enable PRC force projection and influence.31 A dual-use facility is a port or airfield established by a Chinese company that is capable of sustaining and projecting a military contingent for low-intensity operations during the current phase of competition.32 It could become a military base in the future, but is a commercial facility in its initial state.33 In a potential phase of conflict, despite being easily isolated or suppressed, a base could be used to impose risk or to interdict allied lines of communications. Of course, the PRC’s aims for a base may also extend to post-conflict objectives. During competition, however, viable dual-use facility proposals in Melanesia (see the map below) normally deliver a fundamental development need for the host nation.

Even so, facilities are of no use without permission to access them. The clearest example of China achieving geostrategic access in the Pacific is Solomon Islands. The PRC embassy deftly manipulated the opportunity created by the November 2021 riots in Honiara, with political statecraft incorporating security statecraft to protect economic interests. The draft Security Framework Agreement, leaked in March 2022, opens strategic space for China but narrows strategic options for Solomon Islands.34 Access enables the utility of dual-use facilities and requires the support of political and economic statecraft to make it possible.

PRC Integrated Statecraft in Melanesia (2014–22)

Integration and Adaptation

The delivery of grand strategy requires the integration of resources, actions, and effects across the domains of statecraft to shape the achievement of long-term goals. Ideally the strengths of one means should be used to mitigate the weakness of another. However, statecraft must also be adapted with nuance to the local environment, or it will fail to achieve influence. This ultimately leaves the delivery of China’s grand strategy in the hands of its embassy teams on the ground. It depends on the cohesive, agile, and adaptive employment of national power by the MFA’s ambassador, the Ministry of Commerce’s economic and commercial counselor, and the PLA’s defense attaché, or the Ministry of Public Security’s police adviser in country (depicted on the map).

China’s geoeconomic activities have frequently integrated economic means with supporting influence from political and security statecraft to achieve noneconomic outcomes. Integrated activities have also been led by political or security statecraft. Examples of integrated statecraft range from the establishment of the Ramu NiCo mine in PNG in 2007 to the extension of the Luganville wharf in Vanuatu in 2017 or the extradition of Chinese nationals from Fiji in 2017 and Vanuatu in 2019. APEC 2018 in Port Moresby was one of the more complex examples of integrated Chinese means in the Pacific Islands to date, facilitating a series of geopolitical achievements.

Pacific Agency

As China enhanced the means of its statecraft and changed its behavior to pursue influence in the Pacific Islands from 2017, responses differed between the regional, state, provincial, and local levels. Despite regional consensus over the economic benefits of BRI, Pacific Island nations collectively rejected the PRC’s proposal for an integrated regional approach in May 2022. The “Common Development Vision,” which sought to combine China’s political, economic, and security arrangements across the region, was not accepted because of the lack of consultation by China.35 Pacific leaders and officials were concerned that the proposal would generate division across the region.36 At the state level, the ten Pacific Island nations that are members of BRI believe they are receiving more support from China than they actually do, as multilateral banks continue to fund much of this development.37 They could leverage this situation to have more freedom of choice when dealing with China. It is logical for Pacific Island countries to pursue hedging strategies to protect their sovereignty and interests when confronted with the geopolitical competition that is now dominating their region. Solomon Islands has taken an extra step under the Sogavare regime to a position that may become one of “limited alignment” with the PRC.38 More recently, the Rabuka government in Fiji appears to have pursued a closer relationship with the West.39 Regardless, each country is seeking its own form of strategic space and may well still identify itself as hedging, even if external observers do not.

Interest-based responses occur at the subnational level in the Pacific as well. There are examples of provincial officials placing restrictions on Chinese SOEs to protect local interests, such as the economy, the environment, and customary land. These are evident in PNG, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, and Fiji. Finally, there is the agency and pushback at the grassroots level, where a strong local community may choose to evict Chinese small businesses and create laws to protect the microeconomy from domination by Chinese interests. This is a localized form of protecting strategic space where tribal power structures may resort to violence in securing livelihoods and customary land. This agency at the local level is often misunderstood by China and is likely to result in violence if handled poorly. However, the prospect of violence is increasingly being employed as an opportunity for China’s security statecraft and a vector of Chinese law-enforcement support. It is possible for all four of these levels of agency to occur at the same time and place, and for them to be at odds with each other. This creates a very complex environment for PRC statecraft to adapt to.

Conclusion

Through the enhancement, integration, and adaptation of statecraft on the ground, Chinese representatives continue to deliver the grand strategy of the PRC in the Pacific Islands to enhance its geopolitical influence, expand its geostrategic access, and accumulate resources. Each of these interests plays some role in China’s quest for strategic space in the geographic, human, and information terrain of this important part of the world as the PRC pursues four strategic objectives:

-

- 1. To counter encirclement by penetrating the first island chain

-

- 2. To expand the PRC’s strategic space beyond the second island chain by projecting power and influence

-

- 3. To displace strategic competitors by deterring actions and denying strategic space

-

- 4. To posture for a potential future conflict, in which China would use its geostrategic positioning to interdict and contain its adversaries

For now, the PRC’s focus is on the first three objectives, with the goal of winning the competition for strategic space without fighting for it.

Peter Connolly is an Adjunct Fellow at the University of New South Wales and the Center for Strategic and International Studies with 37 years of experience as an officer in the Australian Army. His PhD dissertation, “Statecraft and Pushback: Delivering China’s Grand Strategy in Melanesia 2014–2022,” will be published in 2024.

Correction (January 23, 2024): An earlier version of this essay stated that the draft Security Framework Agreement was leaked in April 2022 rather than March 2022.

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

Xi Jinping and Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister Peter O’Neill | MAST IRHAM/AFP via Getty Images

China Civil Engineering Construction Company (CCECC) HQ | Peter Connolly

PRC Armored Personnel Carrier | Provided by anonymous photographer to the author with permission to use

Cartography by CIGeography, for NBR | Based on a map by Peter Connolly and the Australia National University, 2021. Data: AIDDATA 2021, Observatory of Economic Complexity 2021, Lowy Pacific Aid Map 2021, MOFCOM Country Guides 2020. Media reports, interviews by Peter Connolly 2014-21

77 alleged “cyber fraud” suspects extradited by PRC Ministry of Public Security police from Nadi (Fiji) to Changchun (PRC) on 5 August, 2017 | Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo

ENDNOTES

- The course was held October 16–30, 2014, at the College of Defense Studies, PLA National Defense University, Changping.

- Major General Zhu Chenghu, Senior Colonel Zhou Bo (PLA Air Force), and Rear Admiral Yin Zhuo, October 17 and 20, 2014.

- Major Generals Pan Zhenqiang and Zhang Yingli, October 22, 2014.

- Ambassador Fu Ying (vice minister for foreign affairs) October 23, 2014; and Counsellor Huang Zheng (Ministry of Foreign Affairs), October 16, 2014.

- Major General Zhu Chenghu (professor of strategy, PLA National Defense University), October 20, 2014. See, for example, the 1998 white paper (p. 3) and the 2000 white paper (p. 6), available at https://www.andrewerickson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/China-Defense-White-Paper_1995_Arms-Control_English.pdf.

- See, for example, Jian Yang, The Pacific Islands in China’s Grand Strategy: Small States, Big Games (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 2, 136–37; Terence Wesley-Smith, “China’s Rise in Oceania: Issues and Perspectives,” Pacific Affairs 86, no.2 (2013): 351–72; and Yu Changsen, “Chinese Economic Diplomacy toward the Oceanian Island Countries in the First Decade of the 21st Century,” in 2014 Blue Book of Oceania: Annual Report on Development of Oceania 2013–14 (Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press, 2015), 368.

- See, for example, Lee Jones and Shahar Hameiri, Fractured China: How State Transformation Is Shaping China’s Rise (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 3.

- Stephen Dziedzic and Nick Sas, “Solomon Islands PM Sogavare Insists China Has No Strategic Interest in Pacific after New Police Pacts Signed,” ABC News (Australia), July 13, 2023.

- Liu Yazhou, “The Grand National Strategy”, Chinese Law and Government 40, no. 2 (2007): 35–36. The article was originally written in 2001 and translated into English in 2007.

- Tamara McLean, “Leaks Reveal China’s Strong Ties to Fiji,” Sydney Morning Herald, April 28, 2011, http://www.smh.com.au/world/leaks-reveal-chinas-strong-ties-to-fiji-20110428-1dxz6.html; and “China, Pacific Island Countries Announce Strategic Partnership,” China Daily, November 23, 2014, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/2014xiattendg20/2014-11/23/content_18961677.htm.

- “China’s Interest in the Pacific Islands Is Growing,” Economist, June 2, 2022, https://www.economist.com/china/2022/06/02/chinas-interest-in-the-pacific-islands-is-growing.

- Anna Powles, “Five Things We Learned about China’s Ambitions for the Pacific from the Leaked Deal,” Guardian, May 16, 2022, http://www.the guardian.com/world/2022/may/26/five-things-we-learned-about-chinas-ambitions-for-the-pacific-from-the-leaked-deal.

- Grand strategy is the comprehensive employment of national power to achieve long-term national objectives. Statecraft is the goal-oriented employment of an instrument of state power (political, economic, or security) to generate influence. Statecraft is used to deliver grand strategy.

- Nadège Rolland, China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative, (Seattle: National Bureau of Asian Research, 2017), 119; and Nadège Rolland, China’s Vision for a New World Order, National Bureau of Asian Research, NBR Special Report, no. 83, January 2020, 49.

- Peter Martin, Keith Zhai, and Ting Shi, “As U.S. Culls Diplomats, China Is Empowering Its Ambassadors,” Bloomberg, February 7, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-02-07/as-u-s-culls-diplomats-china-is-empowering-its-ambassadors.

- Interviews with Timorese, Papua New Guinean, Fijian, Australian and American diplomats in 2017.

- An ambassador who has served as a deputy director-general in the MFA is high-quality, knows the strategy, and is trusted to execute it. Seven departments in the MFA coordinate regional affairs.

- I was given these figures by a member of the Chinese business community in PNG, and they are supported by data from the Ministry of Commerce’s 2018 and 2020 guides to PNG.

- Interviews at ADB, Port Moresby, 2019.

- Interviews with SOE executives, PRC officials, and entrepreneurs in Port Moresby and Port Vila, 2019.

- Peter Connolly, “The Belt and Road Comes to Papua New Guinea,” Security Challenges 16, no. 4 (2020): 56.

- Interviews with SOE executives and PRC officials in Port Moresby and Port Vila in 2019.

- Interviews with SOE employees and business entrepreneurs in Port Moresby 2019.

- Kirsty Needham, “China Firm Wins Solomon Islands Port Project as Australia Watches On,” Reuters, March 22, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/chinese-company-wins-tender-redevelop-solomon-islands-port-official-2023-03-22.

- Interviews with SOE employees and business entrepreneurs in Port Moresby and Vanuatu, 2019.

- According to AidData, a combination of hidden and sovereign debt to China represents 17.2% of PNG’s GDP, 22.5% of Vanuatu’s, 8.4% of Fiji’s, 0% of Timor-Leste’s, and an unknown percentage of Solomon Islands’. Ammar A. Malik et al., “Banking on the Belt and Road: Insights from a New Global Dataset of 13,427 Chinese Development Projects,” AidData, William & Mary, September 2021, 94.

- Admiral Sun Jianguo, quoted in Rush Doshi, The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 206. Sun was deputy chief of the Joint Staff Department at the time. See also State Council Information Office (PRC), China’s Military Strategy (Beijing, May 2015), 3–4, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/Database/WhitePapers/index.htm.

- State Council Information Office (PRC), China’s Military Strategy 2015, 3–6.

- Discussions with PLA officers and academics during 2014–17 in China and Australia.

- Nine police officers from the PRC Ministry of Public Security arrived on January 26, 2022. The team is now in its fourth rotation and was expanded for the 2023 Pacific Games in Honiara. Stephen Dziedzic, “China Sending More Police, Donating Equipment Including Drones to Solomon Islands for Pacific Games,” ABC News (Australia), November 1, 2023, https://www .abc.net.au/news/2023-11-01/china-sending-more-police-to-solomon-islands-for-pacific-games/103048778.

- Shou Xiaosong, ed., The Science of Military Strategy (Beijing: Military Science Press, 2013), 254, translated by Project Everest for In Their Own Words: Foreign Military Thought—Science of Military Strategy (2013), (Montgomery: China Aerospace Studies Institute, 2018), 320; and Rear Admiral Yin Zhou, quoted in Christopher D. Yung et al., “‘Not an Idea We Have to Shun’: Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements in the 21st Century,” Institute for National Strategic Studies, National Defense University, China Strategic Perspectives, no. 7, 2014, 13.

- These include humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, evacuation, or stabilization operations. Likely platforms include the Type 071 Yuzhao-class amphibious transport dock and the Xian Y-20 heavy military transport aircraft.

- Yung et al., “Not an Idea We Have to Shun,” 17.

- The leaked agreement states that “China may, according to its own needs,” replenish and transition military forces through the Solomon Islands “to protect the safety of Chinese personnel and major projects in Solomon Islands.” “(Draft) Framework Agreement Between the Government of the People's Republic of China and the Government of the Solomon Islands on Security Cooperation,” posted on Twitter by Anna Powles, March 24. 2022, art. 1–7, twitter.com/AnnaPowles/status/1506845794728837120/photo/> accessed 24 March 2022.

- Lance Polu, “‘No One Asked Us’—PM Fiamē on Geopolitics and the Pacific Region,” Talamua Online News, May 31, 2022, https://talamua.com/2022/05/31/no-one-asked-us-pm-fiame-on-geopolitics-and-the-pacific-region.

- See, for example, the letter from President David W. Panuelo to Pacific Island Leaders, May 2022, 3, 7.

- Connolly, “The Belt and Road comes to Papua New Guinea.”

- Stephen Dziedzic and Nick Sas, “Solomon Islands PM Accuses Australia of Pulling Budget Support, Foreign Interference,” ABC News (Australia), July 17, 2023, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-07-17/solomon-islands-pm-says-china-filled-gap-left-by-aus-nz/102609050.

- Kirsty Needham, “New Fiji Government Suspends Police Commissioner, Scraps China Policing Agreement,” Reuters, January 26, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/new-fiji-govt-suspends-police-commissioner-scraps-china-policing-arrangement-2023-01-27.