Testimony

Promoting American Jobs

Reauthorization of the U.S. Export-Import Bank

On June 4, 2019, Roy D. Kamphausen testified before the U.S. House Committee on Financial Services at a hearing on “Promoting American Jobs: Reauthorization of the U.S. Export-Import Bank.” Kamphausen is Senior Vice President for Research at the National Bureau of Asian Research and a Commissioner on the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. Read his prepared statement below or view the webcast on the House Committee on Financial Services website: Hearing on Promoting American Jobs: Reauthorization of the U.S. Export-Import Bank.

Testimony before the

House Committee on Financial Services

United States House of Representatives

Hearing on

“Promoting American Jobs: Reauthorization of the U.S. Export-Import Bank”

Testimony by Roy D. Kamphausen

Commissioner

U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission

June 4, 2019

Chairman Waters, Ranking Member McHenry, distinguished members of the Committee,

Thank you for the opportunity to appear before you today to share my views on China’s economic policy, especially as it is reflected in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). I want to recognize the Committee’s vigilance for bringing to the public’s attention this important issue, which is the subject of my testimony today. These views are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, where I serve as a Commissioner, although they are informed by the Commission’s body of past and ongoing work on this subject.*

I. Overview of the Belt and Road

A year and a half ago, in testimony before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, I argued that the BRI represents a test case for China’s vision for a new international order throughout Eurasia, and possibly even the world. The contours of that desired order are now more clear, and Beijing’s ambitions even greater, than they were even that short time ago.

Today, China has demonstrated that it intends for the BRI to be not merely a regional initiative, but a global one. China has extended the BRI into the Western Hemisphere, Europe, and the Arctic, and has launched what it calls a “Digital Silk Road” and a “Space Silk Road,” seeking influence not only around the world, but also in the key domains of cyberspace and outer space.

More broadly, China has used the BRI to promote its global influence in areas from increasing market access and setting standards for emerging technologies to controlling global media markets, exporting authoritarian-enabling surveillance technology, and revising the rules of global economic governance. In a speech marking the fifth anniversary of the BRI in August 2018, Xi Jinping declared that the initiative “serves as a solution for China to improve global economic governance […] and build a ‘community of common human destiny’”—a term used with increasing frequency by Chinese leaders to refer to a global order aligned to Beijing’s liking.[1]

Military implications of the BRI have also begun to emerge, as China has spoken openly about the military utility of BRI investments and the need to extend its military reach to protect these commitments. For these reasons, it is likely that China will continue to increase its global engagement; People’s Liberation Army bases in Djibouti and Argentina are unlikely to be their last.

While China has signaled it may be willing to make some rhetorical or tactical adjustments to the BRI in response to the mounting global criticism it has received, there is no indication it will fundamentally alter the project’s most problematic practices. As China continues to add new BRI signatories and reinforces the scheme’s centrality to Chinese foreign policy, we should expect instead that China will only redouble efforts to establish the economic policies represented by the BRI as enduring and accepted features of the global economic order.

For the purposes of this hearing, I will focus on the core economic strategy of the BRI while also discussing how China has used the project to extend its political and military influence more broadly.

II. BRI Aims to Boost China’s Long-Term Economic and Tech Competitiveness

Although Chinese officials like to talk up BRI as a boon to global development, and BRI investment may well provide some necessary resources to urgent infrastructure investment shortfalls throughout Eurasia, from Beijing’s perspective BRI is designed primarily to boost the competitiveness and innovative capacity of Chinese companies. Specifically, BRI aims to (1) open up new markets for Chinese products, particularly in higher-end manufactured goods;[2] and (2) promote adoption of Chinese technology standards.[3] These efforts, if successful, will create long-term reliance on Chinese IP and technology, and disadvantage U.S. and other foreign companies.[4]

BRI is aligned with China’s economic development plans, such as the 13th Five-Year Plan and the Made in China 2025 initiative. For example, BRI directly targets at least half of ten key high-technology sectors in the Made in China 2025 strategy: aerospace equipment, power equipment, new information technology, rail equipment, and marine technologies.[5]

Telecommunications is a particularly notable example of China’s effort to sell technology in BRI markets and beyond. Chinese telecommunications companies are expanding their efforts to build telecommunications infrastructure, provide network services, and sell communications equipment in BRI countries.[vi] Huawei, China Mobile, and ZTE are closely involved in developing 5G technology and have increased their participation in international standard-setting bodies for 5G.†[7] According to research by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), as of April 2019, Chinese companies were involved in 52 5G initiatives in 34 countries.[8]

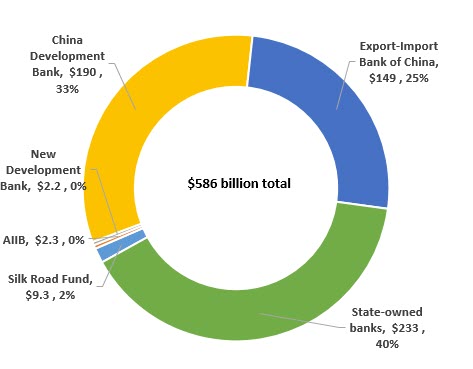

Estimating the value of BRI projects is a challenge. The Chinese government does not release consistent, disaggregated statistics; private sources, likewise, are not comprehensive (one estimate cites $1 trillion, another as much as $8 trillion).[9] Based on what we do know, it is clear that most financing comes from China’s policy banks and state-owned commercial banks (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: BRI Funding by Source

(Outstanding loans or equity investments at year-end 2018, US$ billions)

Source: Various.[13]

China’s banks do not operate the same way as banks in liberal economies do—policy, not profit maximization underpins decision making. In practice, this means that favored industries and companies receive subsidized financing, and projects promoted by the government (even those that lack commercial viability) get preferential access to capital.[10] This enables Chinese companies to underbid other competitors, who do not enjoy similar subsidies. In a recent example, Huawei, a “national champion” and one of the world’s most prolific providers of telecommunications infrastructure, won a contract to supply 5G equipment to a Dutch wireless carrier by underbidding the existing vendor, Swedish firm Ericsson, by 60 percent.[11] Furthermore, most BRI projects are not open tender and are awarded to Chinese companies, relegating foreign companies to supporting roles, if they can get access at all.[12]

The Chinese government also provides credit to foreign governments and businesses to purchase Chinese equipment and services. According to data from the U.S. Export-Import Bank, in 2017, China provided $36.3 billion in official export credit, or one-third of the global export credit.[14] Huawei is a notable beneficiary of Chinese government largesse. According to its annual reports, Huawei received $1.6 billion in government grants over the last 10 years.[15] At the same time, local governments offered Huawei heavily subsidized land to build its facilities while state-controlled banks have helped bankroll Huawei’s global expansion: For example, in 2004, the China Development Bank gave Huawei a $10 billion credit line to provide financing to clients buying its gear, which was tripled to $30 billion in 2009.[16] According to a report by Washington Post, China’s state-owned banks also made $100 billion available to Huawei clients to purchase its equipment.[17]

III. BRI as a Tool to Promote Political and Military Influence

While China routinely denies any strategic motivation behind the BRI, the project’s political and military components are apparent. Moreover, as the self-proclaimed test platform for China’s “community of common human destiny,” the political and military aims China has advanced through the BRI offer a troubling preview of what a world serving the interests of China’s political system might resemble.

In countries from Africa to Europe and the Western Hemisphere, China has used BRI partnerships to expand its influence into local media markets and export digital surveillance technology and other means of social control. In April, China hosted the inaugural meeting of the Belt and Road News Network—an association consisting of 182 media outlets from South Africa to France—where Xi Jinping exhorted countries involved in the BRI to produce news stories boosting public support for the project.[18] The establishment of this network builds on longstanding Chinese investments around the globe to fund foreign journalists travelling to China for training in Chinese state-run media practices, purchase controlling stakes in foreign Chinese-language and other media, and promote China’s concept of cyber sovereignty that would give governments the right to control internet users and content within its territory.[19]

As China has perfected its application of digital surveillance at home, including the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and big data to support its detention of more than a million Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in China’s Xinjiang region, it has increasingly exported these surveillance methods abroad, including through the Digital Silk Road. According to a 2018 report by Freedom House, of 65 countries surveyed, 18 had purchased surveillance equipment, including AI-enabled facial recognition systems, from Chinese companies. Further, Freedom House found 38 countries have purchased internet and mobile network equipment from China, and officials from 36 countries have received information management training from China.[20]

On the military side, recent statements and writings from Chinese leaders have reinforced the military significance of the BRI and the potential military utility of certain BRI investments—especially those in ports, airports, and railways. In January, Xi Jinping called on China to improve the protection of its overseas economic interests, including through building what he called a “system of security guarantees” for the BRI. In 2018, China’s minister of defense used similar language to announce the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) interest in working with Pakistan to provide a security guarantee for BRI projects.[21] In a recent article expanding on this directive, a PLA officer revealed the existence of a military “going global” strategy that requires the PLA to routinize military activities outside China’s borders while encouraging the use of BRI investments to support overseas power projection.[22] The exact methods the PLA might employ to ensure the security of its BRI investments—such as enhanced security cooperation, capacity building of host nation security forces, outsourcing of security to private security providers, and even potentially the deployment of active PLA forces in certain circumstances—remain under development.

IV. Examples of Pushback to the BRI and China’s Response

Almost from its inception, BRI has raised concerns about debt sustainability in recipient countries. China does not follow international development finance standards, and does not disclose the amounts or the terms for loans it offers.[23] Analysis by Aid Data, a research lab at the College of William & Mary, shows that most of China’s state lending overseas is based on commercial, nonconcessional terms.[24] A March 2018 report from the Center for Global Development assessed the current debt vulnerabilities of countries identified as potential BRI borrowers. Out of 23 countries determined to be significantly or highly vulnerable to debt distress, the authors identified eight countries “where BRI appears to create the potential for debt sustainability problems, and where China is a dominant creditor in the key position to address those problems.”[25] One of these eight countries, Djibouti, received financing from China worth nearly $1.4 billion, or around 75 percent of Djibouti’s GDP, which almost certainly played a role in the country’s agreement to host a Chinese naval base.[26]

Although China often makes deals with countries vulnerable to economic distress and political coercion due to poor governance, weak financial regulations, and corruption, a number have spoken out about their concerns over the debt and sovereignty risks associated with BRI loans.[27] Hambantota, a deep-sea port in Sri Lanka, illustrates a warning case of these problematic trends: In 2018, struggling to pay its debts to China (which totaled $8 billion by one estimate) and other creditors, Sri Lanka’s government turned over a controlling equity stake and a 99-year lease to China.[28]

In a notable example of pushback Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad spoke out during a trip to Beijing last year about his concern over the exorbitant costs of BRI projects in his country, warning against BRI partnerships giving way to a “new version of colonialism.”[29] As a result of this pushback, Malaysia successfully lowered the price tag of its largest BRI project by a third, while it was revealed that in 2018 a team of U.S. experts dispatched by the U.S. Agency for International Development assisted Myanmar in renegotiating the cost of a major BRI port deal from $7.3 billion to $1.3 billion, suggesting other BRI recipients may be interested in similar outside assistance.[30]

Recognizing the need to reinforce global norms and best practices for development aid and investment, a number of countries—including the United States, Japan, India, and European countries—have announced new projects to provide countries in need of infrastructure assistance with alternatives to the terms of China’s BRI.[31] More recently, following the passage of the BUILD Act, Australia, Canada, the European Union, and Japan signed multilateral cooperation agreements with the revitalized U.S. Overseas Private Investment Corporation to drive growth in emerging markets that adhere to high standards and provide alternatives to “unsustainable state-led models.”[32]

Still, while China has been sensitive to the growing backlash against the BRI, it does not appear to have fundamentally altered the initiative’s most problematic components or diminished its efforts to gain acceptance of the BRI as a legitimate model for extending China’s political, economic, and military influence abroad. At a world summit for BRI participants in April, Xi Jinping sought to assuage countries’ concerns over the BRI but restated China’s view of the project’s significance as a new model for global economic governance.[33] With the continued addition of new signatories to the BRI, including Italy’s accession over the strong protests of the United States and European Union, Beijing may have grounds to remain confident in the prospects for the project’s viability. Despite protests over their BRI debts, countries have refrained from canceling projects outright and opted instead to renegotiate better terms, suggesting the ultimate fate of China’s model may hinge on the ability of the United States and its allies and partners to reinvigorate alternative programs to address the vast global development needs.

V. Recommendations

BRI’s geographic ambition and variety and scale of projects may make it seem like an insurmountable challenge to the global liberal order. While this is not yet true, the United States and its allies and partners must be vigilant in monitoring Chinese activities and relentless in protecting our interests. More than anything, we should be proactive—not reactive—when formulating the U.S. response to the BRI. Trying to match China dollar-for-dollar is not possible, nor would it make for good policy. The U.S. should always play to our strengths and offer assistance to countries seeking alternatives to China’s predatory practices. The U.S.-China Commission made 26 recommendations in its 2018 Annual Report to Congress to help bolster U.S. economic, security, and diplomatic capabilities pertinent to our relationship with China. Excerpted below are some of the recommendations I think are particularly relevant to your inquiry:

- Congress create a fund to provide additional bilateral assistance for countries that are a target of or vulnerable to Chinese economic or diplomatic pressure, especially in the Indo Pacific region. The fund should be used to promote digital connectivity, infrastructure, and energy access. The fund could also be used to promote sustainable development, combat corruption, promote transparency, improve rule of law, respond to humanitarian crises, and build the capacity of civil society and the media.

- Congress require the U.S. Department of State to prepare a report to Congress on the actions it is taking to provide an alternative, fact-based narrative to counter Chinese messaging on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Such a report should also examine where BRI projects fail to meet international standards and highlight the links between BRI and China’s attempts to suppress information about and misrepresent reporting of its human rights abuses of Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

- Congress require the Director of National Intelligence to produce a National Intelligence Estimate (NIE), with a classified annex, that details the impact of existing and potential Chinese access and basing facilities along the Belt and Road on freedom of navigation and sea control, both in peacetime and during a conflict. The NIE should cover the impact on U.S., allied, and regional political and security interests.

*The U.S.-China Commission published a chapter on the BRI in its 2018 Annual Report to Congress. The research and findings from that chapter are central to arguments made in this testimony, which draws heavily on that and other Commission analysis.

†For discussion of Chinese entity participation in 5G standards-setting bodies, see U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2018 Annual Report to Congress, November 2018, 453–455.

Endnotes

[1] Xinhua, “Xi Pledges to Bring Benefits to People through Belt and Road Initiative,” August 27, 2018.

[2] Nadège Rolland, “China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative,” National Bureau of Asian Research, May 2017, 98; Gabriel Wildau and Nan Ma, “In Charts: China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” Financial Times, May 10, 2017.

[3] Xinhua, “China to Promote Application of 5G National Standards in B&R Countries,” December 26, 2017; Economist Intelligence Unit, “China’s Digital Silk Road,” May 14, 2018; Peter Cai, “Understanding China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” Lowy Institute for International Policy, March 2017, 9-11.

[4] Peter Cai, “Understanding China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” Lowy Institute for International Policy, March 2017, 9-11; Andrew Polk, “China is Quietly Setting Global Standards,” Bloomberg, May 6, 2018.

[5] U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Five Years Later, written testimony of Nadège Rolland, January 25, 2018, 5.

[6] Zen Soo, “ZTE to Play Integral Role in Creating ‘Information Superhighway’ to Connect One Belt, One Road Countries,” South China Morning Post, December 2, 2016; Ernst & Young, “Key Connectivity Improvements along the Belt and Road in Telecommunications and Aviation Sectors,” September 2016, 12-15.

[7] U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China, The United States, and Next-Generation Connectivity, written testimony of Doug Brake, March 8, 2018, 5–6.

[8] Danielle Cave et al., “Mapping China’s Technology Giants,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, April 18, 2019, 3. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/mapping-chinas-tech-giants.

[9] Jane Perlez and Yufan Huang, “Behind China’s $1 Trillion Plan to Shake up the Economic Order,” New York Times, May 13, 2017; Cheang Ming, “China’s Mammoth Belt and Road Initiative Could Increase Debt Risks for 8 Countries,” CNBC, March 5, 2018.

[10] Investment & Pensions Europe, “China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Q&A with Ben Way, Macquarie,” December 2017; Shu Zhang and Matthew Miller, “Western Banks Eclipsed by China’s along the New Silk Road,” Reuters, May 17, 2017; Tom Hancock, “China Encircles the World with One Belt, One Road Strategy,” Financial Times, May 3, 2017.

[11] Ellen Nakashima, “U.S. Pushes Hard for a Ban on Huawei in Europe, but the Firm’s 5G Prices are Nearly Irresistible,” Washington Post, May 29, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/for-huawei-the-5g-play-is-in-europe–and-the-us-is-pushing-hard-for-a-ban-there/2019/05/28/582a8ff6-78d4-11e9-b7ae-390de4259661_story.html?utm_term=.4e0c473a4d0f.

[12] Financial Times, “China’s Belt and Road Initiative Is Falling Short,” July 29, 2018; Jonathan E. Hillman, “The Belt and Road’s Barriers to Participation,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, February 7, 2018.

[13] “China’s EximBank Provides More than $149 Bln for Belt and Road Projects,” Reuters, April 18, 2019; David Tweed, “China’s New Silk Road,” Bloomberg, April 16, 2019; New Development Bank, “List of All Projects.” https://www.ndb.int/projects/list-of-all-projects/; Silk Road Fund, “News and Press Releases.” http://www.silkroadfund.com.cn/enweb/23809/23812/index.html; AIIB, “Approved Projects.” https://www.aiib.org/en/projects/approved/index.html.

[14] Export-Import Bank of the United States, Report to Congress on Global Export Competitiveness, June 2018, 19. https://www.exim.gov/sites/default/files/reports/competitiveness_reports/2018/EXIM-Competitiveness-Report_June2018.pdf.

[15] “Huawei a Key Beneficiary of China Subsidies that U.S. Wants Ended,” AFP, May 30, 2019.

[16] “Huawei a Key Beneficiary of China Subsidies that U.S. Wants Ended,” AFP, May 30, 2019.

[17] Ellen Nakashima, “U.S. Pushes Hard for a Ban on Huawei in Europe, but the Firm’s 5G Prices are Nearly Irresistible,” Washington Post, May 29, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/for-huawei-the-5g-play-is-in-europe–and-the-us-is-pushing-hard-for-a-ban-there/2019/05/28/582a8ff6-78d4-11e9-b7ae-390de4259661_story.html?utm_term=.4e0c473a4d0f.

[18] Abdi Latif Dahir, “China Wants to Use the Power of Global Media to Dispel Belt and Road Debt Risks,” Quartz Africa, April 25, 2019.

[19] U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2018 Annual Report to Congress, November 2018, 314-317; U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2017 Annual Report to Congress, November 2017, 482-484.

[20] Freedom House, Freedom on the Net 2018, October 2018, 8.

[21] Xinhua, “Xi Urges Major Risk Prevention to Ensure Healthy Economy, Social Stability,” January 22, 2019; China Military Online, “Chinese Defense Minister Meets Pakistani Naval Chief of Staff,” April 29, 2018.

[22] Chen Yu, Liang Si, and Zeng Yu, “Research on the Development of Overseas Strategic Airlift Capability,” Military Transportation University Journal, February 2019. Translation.

[23] John Hurley, Scott Morris, and Gailyn Portelance, “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective,” Center for Global Development Policy Paper, March 2018, 4; David Dollar, “Is China’s Development Finance a Challenge to the International Order?” Brookings Institution, October 2017, 6; U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Five Years Later, written testimony of Daniel Kliman, January 25, 2018, 3; AidData, “How to Use Global Chinese Official Finance Data.”

[24] Axel Dreher et al., “Aid, China, and Growth: Evidence from a New Global Development Finance Dataset,” Aid Data Working Paper, October 2017, 14.

[25] John Hurley, Scott Morris, and Gailyn Portelance, “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective,” Center for Global Development Policy Paper, March 2018, 8, 11.

[26] John Hurley, Scott Morris, and Gailyn Portelance, “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective,” Center for Global Development Policy Paper, March 2018, 16.

[27] John Hurley, Scott Morris, and Gailyn Portelance, “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective,” Center for Global Development Policy Paper, March 2018, 2.

[28] Kai Schultz, “Sri Lanka, Struggling with Debt, Hands a Major Port to China.” New York Times, December 12, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/12/world/asia/sri-lanka-china-port.html.

[29] Hannah Beech, “‘We Cannot Afford This’: Malaysia Pushes Back against China’s Vision,” New York Times, August 20, 2018.

[30] Channel News Asia, “‘The Belt and Road Initiative is Great: Malaysia PM Mahathir,” April 26, 2019; Ben Kesling and Jon Emont, “U.S. Goes on the Offensive against China’s Empire-Building Funding Plan,” Wall Street Journal, April 9, 2019.

[31] U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2018 Annual Report to Congress, November 2018, 282-287.

[32] Overseas Private Investment Corporation, “US, Japan, Australia Sign First Trilateral Agreement on Development Finance Collaboration, November 12, 2018; Overseas Private Investment Corporation, “OPIC Signs MOU Establishing DFI Alliance with Key Allies,” April 11, 2019.

[33] Xinhu, “Xi’s Keynote Speech at the Opening Ceremony of the Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation,” April 27, 2019.