Interview

Burden and Boon

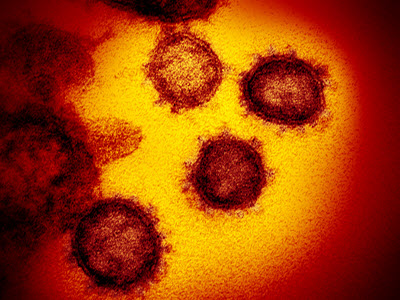

What Covid-19 Means for Global Health R&D

Global health R&D includes the research and development of new vaccines, drugs, and diagnostics for diseases that disproportionately affect populations in poorer countries. In this interview, Melinda Moree, a leading global health consultant, discusses what the Covid-19 pandemic means for the future of global health R&D funding, collaboration, and infrastructure, as well as how existing R&D is being used to help turn the tide against the pandemic.

What does the international policy community need to understand about the history of global health R&D to better appreciate the implications of Covid-19?

Global health is a relatively young field. I was a fellow with the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C., in 1992. And at that time, we had trouble finding investment in any global health tools. A vaccine group had just begun forming to address issues of equal access, and it was very difficult to get any money directed toward R&D for diseases that mostly affected poor people in developing counties. Around the year 2000, however, a major shift happened for global health R&D. This shift was driven in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and in part by individuals in for-profit pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies who drove programs forward just by being global health champions.

Back then, the global health community had little idea of the amounts of money that the Gates Foundation would invest over time. By making this financial commitment, the foundation attracted other players to global health R&D. A lot of governments—the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, for example—also started investing more money in R&D, which is not typically what they invest in. Those developments created considerable momentum, opening the door for other investors.

What was the state of global health R&D before the pandemic?

What’s come out of those efforts over the last twenty years is amazing: new drugs for malaria, a malaria vaccine that’s being further tested in Africa, and new diagnostics, to name just a few accomplishments. Investment in global health R&D has paid off not just in terms of better research but also in terms of new vaccines, drugs, and diagnostics that are saving lives. The progress made in a relatively short time frame (for life science product development) is remarkable.

Who are the key global health R&D players in Asia?

There are many, but let me share examples of important stakeholders in three Asian countries.

First, Japan offers a great example of a public-private partnership on global health R&D through an international entity. The Japanese government and Japanese life science companies have brought significant investment and high-level policy attention to global health R&D on their own and also collectively by forming the Global Health Innovative Technology Fund (with the Gates Foundation). The fund invests in global health R&D by matching government and foundation investments with company investments in a novel way. No other country that I can think of has that kind of collaboration where companies are actually investing their own dollars as well. And the collaboration is international: partners from around the globe are being linked with Japanese companies and researchers. Many drugs, diagnostics, and vaccines are moving through its portfolio.

Second, China is a powerhouse on the research side, but Chinese companies have not widely exported drugs, vaccines, and diagnostics because they have such a huge population to serve domestically. Most Chinese technologies have traditionally stayed within the country. What’s happening now is that Chinese stakeholders are beginning to look outside China and increasingly dealing with all the policies and laws about export, import, and regulatory systems in other countries.

Third, Indonesia is home to the vaccine company Bio Farma, which is working with a Chinese company to do clinical trials of a Covid-19 vaccine in Indonesia. The expectation is that, as part of that arrangement, Bio Farma will receive a technology transfer to produce and sell the vaccine.

Asian stakeholders in global health R&D have historically been a bit more internally focused. But in the past several years, even before the Covid-19 pandemic, they have reached outside those boundaries and really engaged in driving global work, as opposed to just driving R&D coming out of their country. This trend is exciting. Asia has a huge role to play in R&D on Covid-19 treatments. For example, there are many clinical trials that go on in different Asian countries because of the strengths of the regulatory systems and scientists across the region.

What are the financial implications of the Covid-19 pandemic for global health R&D?

In donor assistance, certain priorities will cycle for a while and get a lot of attention, before a new focus comes along. Besides just the need for novelty, there’s also the reality of new challenges, like HIV/AIDS in the 1990s and Covid-19 today, that drive resources. Those investments always have an upside and downside. But I would say that donor focus on global health R&D has not always existed, or at least has not been consistent.

Policy Cures in Australia tracks global health R&D investments—both dollar amounts and sources of funding. Investment is one key metric that helps us measure whether and how interest is growing, shrinking, or staying the same. What we’ve seen is that worldwide investment in global health R&D was stagnant for the last two or three years. Then in 2020, when a threat as fundamental as Covid-19 emerged, the ongoing challenges of malaria and tuberculosis were no longer quite as interesting to investors and donors. As a result, there may be a shift of resources, particularly government resources. Before Covid-19, it was challenging to keep the attention of government funders and foundations on global health R&D. The pandemic has taken that already shaky commitment and shaken it further.

Funding is a persistent challenge, but in some ways global health was a victim of its own success before the outbreak of Covid-19. Because so many drugs, vaccines, and diagnostics had been developed and were moving through the pipeline to the later stage of testing, R&D became very expensive. That cost increase in the later stage of development is typical, but it poses a special challenge for global health R&D, which struggles for funding at every step. How to pay for this stage, which is usually when companies enter the process, is not at all straightforward. So far, investment has not matched that need.

Infectious and neglected tropical diseases that disproportionately affect the developing world (like malaria, tuberculosis, and many parasitic diseases) still persist, and the resources to develop the tools we need to better diagnose, prevent, and treat them have to come from somewhere. The assumption today is that the resources will be diverted from existing global health work to R&D for Covid-19. I don’t know that we have the data to draw this conclusion definitively yet, but it’s certainly the expectation of many. If true, things will be just that much harder for global health R&D.

We saw this pattern in the 1990s when HIV/AIDS came along and the funding for R&D on malaria and other tropical diseases went down. It was by no means wrong to focus on HIV/AIDS, but other priorities did get pushed to the background a bit. That will likely happen again during the Covid-19 pandemic.

What other challenges has the pandemic created for global health R&D?

When everything essentially locked down and travel became restricted or impossible, global health clinical trials underway throughout the world had to halt very suddenly. This is the reality for clinical trials across the board—in oncology and respiratory diseases, as well as parasitic and neglected diseases. After taking many years and so many people to set up, those trials are all in a holding pattern. One problem is that remaining in a holding pattern costs money. This can possibly work for a little while, but eventually the trials will reach a point where they can no longer afford to do so.

Moreover, it’s quite possible that the donors supporting some of those projects may just give up completely. That abandonment would carry enormous financial and human consequences.

On the plus side, in terms of logistics, companies are exploring ways to conduct clinical trials without everybody flying all over the world. Many people are turning to technology for ways to administer trials more cheaply and from a distance. For example, technology now exists that allows people to self-report whether they had a fever or were otherwise sick. It will be interesting to see what comes out of this.

Does Covid-19 create any opportunities for global health R&D?

In every crisis there are always opportunities. I have never before seen the global community move this quickly and invest this many dollars in trying to develop vaccines, drugs, and diagnostics. What’s already in place for Covid-19 less than a year after discovering the virus is phenomenal.

The World Health Organization put together the ACT-Accelerator, which focuses on creating vaccines, drugs, and diagnostics, and many countries and organizations are involved. In just a few months, we have new vaccines being developed and moving into the later stages of clinical trials. Importantly, shortcuts are not being taken on health and safety. This speed is unprecedented. Vaccine development typically takes an average of ten years, including several years of research before a candidate can even begin the first clinical trials.

Opportunities emerge when the world sees what can be done and when stakeholders truly work together. I hope we can leverage these opportunities for global health R&D down the road.

Is the infrastructure for global health R&D that is already in place across the world being harnessed for Covid-19 solutions?

The developing country vaccine manufacturers already have an official network, in which foundations and governments have invested. And now those manufacturers are really stepping up and partnering. For example, the Serum Institute of India (a member of that collective) has recently made deals with several companies to manufacture a large volume of a Covid-19 vaccine, once approved, to distribute it more quickly.

Those investments in developing countries by the global health community have been going on for years, and in some cases decades. As a result, their vaccine manufacturers were able to step up very quickly, with a much more global look than I think would have otherwise been the case. This will be extraordinarily important when there is a safe, effective, approved Covid-19 vaccine. It also lays important groundwork for the manufacture of other needed vaccines.

Additionally, trial sites are critical resources. Multiple clinical trials containing tens of thousands of people are being held in every part of the world these days. A lot of the resources that have been built in developing countries have come from global health R&D.

What other opportunities might Covid-19 catalyze for the future of global health R&D?

One opportunity is the potential that results from the new vaccine manufacturing capacity being built all over the world. Some of the Covid-19 vaccines will inevitably fail, and there will be manufacturing capacity without anything to manufacture, which creates an opportunity for different global health R&D projects. The unused facilities represent huge investments that companies usually don’t make until they know a product has a good chance of working. Again, during the pandemic, companies and countries are taking bigger financial risks than usual, and global health R&D could benefit in the long run.

Additionally, low- and middle-income countries are not waiting for people to come and save them from Covid-19. They are doing R&D on their own and contributing meaningfully to the global effort. I just read about Rwanda coming up with its own algorithm for how to use fewer tests while diagnosing more people. This represents an enormous opportunity to spread the work of global health R&D to more countries where so many infectious diseases are endemic, and for those countries to participate even more substantively as partners.

As I discussed earlier, new engagement in Covid-19 R&D puts developing country vaccine manufacturers in a global position that many of them have not experienced before. This gives these companies the opportunity to look beyond their own borders for export. And the more companies export, the better their situation commercially.

How and when should global health R&D harness those opportunities?

The challenge is about focus. I remember when all the funding went into HIV/AIDS, and then once that R&D was up and going, people started looking around and asking what they had ignored. That’s when we in the malaria community were ready with our investment case and stepped up. After that, funding for malaria increased from tens of millions to billions in just a few years.

Right now, most of the focus is on Covid-19. But as funders better understand what can be accomplished with the right types of investment, global health R&D will be ready.

Melinda Moree most recently worked for the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness (CEPI), a global alliance to finance and coordinate the development of new vaccines to prevent and contain infectious disease epidemics. Prior to this, she was vice president of professional services at Vital Wave, and before that CEO of Bio Ventures for Global Health, a nonprofit liaison between for-profit biotech and nonprofit global health organizations. Dr. Moree was also executive director of the Malaria Vaccine Initiative, housed within PATH. She has a PhD in medical microbiology from the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and a BA in biology from Lee University.

This interview was conducted by Claire Topal, a Senior Advisor for International Health for the National Bureau of Asian Research.