Biopharmaceutical Innovation

China, India, and Supply Chain Security

The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted both the importance of an innovative biopharmaceutical industry and the risks that can arise from global supply chains in times of crisis. While the United States remains at the forefront of global biopharmaceutical innovation, rapid developments in Asia are accelerating the rise of new players in the industry. In this interview, Linda Distlerath, a senior advisor to NBR, discusses China’s and India’s biopharma sectors, the key elements that foster an innovation-friendly policy environment, and the challenges facing global biopharma supply chains.

You’ve had a really interesting career. Could you describe your career path and some of the highlights?

My 35 years in the global biopharmaceutical and healthcare industry began as a laboratory medical technologist at a small hospital in Ohio. As the first in my family to graduate from college, my goal was to secure a steady job with a degree in hand, but my desire for learning and achievement only grew. I went on to earn a doctorate in environmental health with a specialty in toxicology. I fell in love with research and conducted a postdoctoral fellowship in biochemistry and molecular toxicology.

After completing the fellowship, the blue-chip pharmaceutical company Merck hired me as a clinical research associate. I spent the next 23 years at the company, moving from research to corporate public affairs and global health policy, while also bolstering my education with a law degree. Following my last two years at Merck as an expat in Hong Kong, I shifted gears to lead the global healthcare practice at APCO Worldwide for several years. I then joined PhRMA, the trade association for the innovative biopharma industry, leading international advocacy and strategic alliances with a focus on Asia. Today, I am privileged to serve as an advisor to several organizations—including NBR—and am working to advance the life sciences sector in my home state of South Carolina.

My career highlights center on improving the quality of life for people around the world. While I gained extensive expertise and experience in public affairs and policy—especially in promoting pro-innovation policies concerning intellectual property (IP) protection, science-based regulatory systems, and access to medicines—my “soft skill” strength is in developing and leading public-private partnerships around the world as a strategy to achieve public policy and health goals. That was most evident in the HIV/AIDS field while I was at Merck, and especially in the creation of groundbreaking partnerships to improve access to HIV care, prevention, and treatment in the United States, sub-Saharan Africa, and China. Knowing that this work reduced the mortality of AIDS in Botswana or reduced HIV transmission in Sichuan Province is what has made my career so rewarding.

China is rapidly becoming a global leader in the biopharmaceutical sector. What is driving this progress, and what challenges remain?

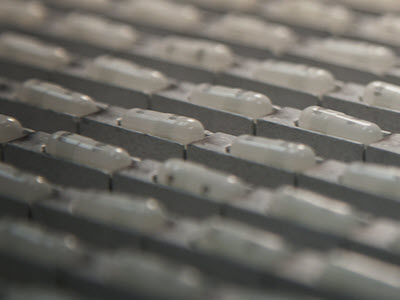

China is strong in the lower-value end of the biopharmaceutical supply chain involving the production of generic drugs, active pharmaceutical ingredients, and chemical intermediates. Moving up the value chain to develop and commercialize world-class innovative drugs and vaccines not only takes significant investment but requires a public policy environment—in both China and its target markets—that enables sustained investment.

Drug and vaccine R&D is a long-term process that is risky and expensive. Only 12% of drugs that enter clinical trials achieve FDA or other regulatory agency approval. On average, the time from discovery to regulatory approval is ten to fifteen years, and the cost to bring a new drug forward from discovery to market is $2.6 billion, including the costs of all those failures. Investment in biopharmaceutical R&D can only be sustained in a policy environment that incentivizes innovation and makes the risk worthwhile. The three major policy pillars for innovation include (1) strong IP protection and enforcement, (2) science-based, transparent, and predictable drug regulatory systems, and (3) drug pricing and reimbursement systems that appropriately value biopharma innovations (also referred to as market access).

In China, there has been significant progress on these pro-innovation policies concerning IP, regulatory systems, drug pricing, and reimbursement since around 2015. Notably, the national formulary listing and reimbursement of innovative drugs from the global biopharma companies have become considerable over the last couple of years. With China now the second-largest biopharmaceutical market in the world, the Chinese government recognizes the potential of its own biopharma sector to become a major player. Pro-innovation policies in China encourage investment by global firms in research and manufacturing facilities and spur partnerships with Chinese companies and academic institutions that help build their innovative know-how and capacity to move up in the global biopharmaceutical world.

However, numerous policies to improve IP or the ability to conduct clinical trials either have been slow to be implemented or have brought new surprises in the details. For example, China is scoring poorly on patent linkage. This is a provision in the regulations of the FDA and other leading regulatory authorities around the world that prohibits the approval of a generic copy of drugs that are still protected by patents. On paper, China has a policy of patent linkage, but it is not being enforced. Just in the past year, the country’s National Medical Products Administration has approved several patent-infringing drugs.

India has also become a major player in the biopharmaceutical field. What progress has India made, and how does its approach differ from China’s?

A fundamental challenge in the Indian healthcare sector is the exceptionally low level of government investment, which is currently only 1% of GDP despite years of promises to raise it to 2.5%. That target is still lower than China’s healthcare expenditures of 3% of GDP and the world average of around 6%. This abysmal level of government investment in health translates to underdeveloped infrastructure, inadequate numbers of trained workers, and provision of only the most basic level of healthcare. Only 37% of the Indian population has any kind of health insurance coverage, and the substantial level of out-of-pocket spending drives families into poverty. Still, a growing middle class in India wants access to high-quality healthcare and the newest medicines, making the country an attractive, emerging market for the innovative biopharma sector.

India prides itself on being the “pharmacy of the world,” supplying 20% of the world’s generic medicines and over half of the vaccines. The Indian government welcomes investment from global biopharma companies and sees opportunities for the leading Indian companies to move up the value chain toward the world-class innovative level.

In contrast to China, however, there has been relatively little sustained progress in India to strengthen the policy pillars of biopharma innovation, especially concerning IP protection. There is a persistent threat of compulsory licensing of patented innovator drugs and continued approval of generic copies of patented drugs by the Indian state-level drug regulators without prior notice to the innovator. While these policies appear to favor the local Indian generic companies, other IP-related policies directly harm those Indian companies aiming to move up the value chain.

The India Patent Act, Section 3d, creates what the global biopharma sector believes are impermissible barriers to patentability for pharmaceuticals under the terms of the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights. Article 27 of the agreement requires that patents be available for any invention in all fields of technology, provided that the product or process is new, novel (nonobvious), and capable of industry application.

India’s patent law adds another criterion for pharmaceuticals—enhanced efficacy. This new hurdle is particularly applied to patent applications for new forms of an original drug. This fourth hurdle discourages innovation to improve on an existing drug to create new dosage forms that increase convenience or compliance for the patient. Under the enhanced efficacy requirement, the improved dosage form is not patentable in India (though it would be in other jurisdictions such as the United States and Europe). This “enhanced efficacy” requirement—along with other weaknesses in India’s patent system—is driving Indian innovators to the United States, China, and other countries where the policy conditions for biopharma innovation are more favorable.

The Covid-19 pandemic has raised concerns regarding pharmaceutical supply chains. How problematic are U.S. pharmaceutical companies’ global supply chains today?

First, I want to note an excellent piece on this topic posted on the NBR website in April 2020 based on an interview with Benjamin Shobert, a senior associate for international health with NBR. As Ben noted, the Covid-19 pandemic has exposed vulnerabilities in the global supply chain for pharmaceuticals and medical products such as personal protective equipment. In China, factories manufacturing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) shut down, air transportation halted, and FDA inspections of facilities were suspended.

Given that China is the source of 80% of APIs used in the world for medicines, yes, we should be concerned. But the solution is not to transfer all manufacturing of these ingredients to the United States; rather, we should focus on the most critical products for national security and leverage the full force of regulatory tools.

Today, APIs in the medicines consumed in the United States come through three different mechanisms. First, APIs can be manufactured in the United States to make the final dosage form (e.g., tablet or capsule). Second, they can be manufactured outside the United States and then exported here for the final dosage form. A third possibility is that both the APIs and the final dosage form are manufactured in other countries and then exported to the United States. A July 2020 report by Avalere indicated that 54% of the value of APIs used in U.S. medicines was made in the United States, with 19% coming from Ireland and only 6% from China. That may sound good, but it could mean that an exceptionally large volume of low-priced generic medicines in the United States contain Chinese-sourced APIs. Specifically, the 6% from China may be of concern if those medicines are deemed most critical with few or no other suppliers of APIs.

The U.S. Congress is anxious to reduce U.S. dependence on China or other countries for critical pharmaceuticals. A popular choice is to repatriate or re-shore the production of pharmaceuticals back to the United States. However, undoing the large and established global supply chains, including those involving China (for pharmaceuticals or other products), would be difficult and costly. I concur with Ben Shobert’s view that a more practical and longer-term solution is to strengthen the regulatory framework—especially between the United States and China—to ensure quality, transparency, and resiliency in the pharmaceutical supply chain.

What policies should the United States and other countries pursue to ensure supply chain stability and safeguard against unforeseen disruptions in the future?

The Association for Accessible Medicines, the trade association for the U.S. generics industry, suggested some practical policies in its blueprint to address concerns in the global supply chain for pharmaceuticals: (1) identify the list of medicines most critical for U.S.-based manufacturing, (2) provide grants and tax incentives to secure the U.S. drug supply chain (through repatriation or re-shoring of manufacturing facilities), (3) supply the Strategic National Stockpile, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and other agencies with essential medicines for the long term, (4) reduce regulatory inefficiencies to streamline approval for U.S.-based manufacturing facilities, considering that it takes five to seven years and up to $1 billion to build a new facility, and (5) promote global cooperation—including with China—in diversifying and securing the global supply chain.

What advice do you have for young women interested in a career in the biopharmaceutical sector?

The biopharmaceutical industry offers an extraordinary range of career opportunities across numerous disciplines and geographic regions: basic and clinical research, biostatistics, engineering of all kinds, environment/sustainability sciences, sales and marketing, legal services, public policy, and government affairs, among others. While the industry is STEM-intensive, it is not STEM-exclusive!

My number one recommendation is to talk to people in the biopharma industry about their roles and career paths. This not only increases your knowledge but also builds an essential network of contacts that will help you identify and land a position in the industry. Reach out to national- or state-level organizations that promote the life sciences, healthcare, and the biopharma sector. Many organizations have student programs or reduced membership fees for those in the early phase of their careers. For example, the Healthcare Businesswomen’s Association has 55 chapters across the United States, Canada, and Europe, with the biopharma industry being well-represented. Also search for local community, hospital, or university events sponsored by biopharma companies. Many are open to the public and offer the opportunity to meet experts and learn about the programs of interest to the companies.

Finally, university academic departments and faculty members often have relationships with executives from biopharma companies based on grant programs, contract research, and other collaborative initiatives. Talk with faculty members about your interest in the industry and ask for introductions to their contacts to secure an informational interview.

Linda Distlerath is a Senior Advisor to NBR. She is also a Trustee of the South Carolina Research Authority and serves on the board of the National Academy of Certified Care Managers. She is a healthcare industry expert with over three decades of experience in the global biopharmaceutical sector, bringing substantial expertise in public affairs and building favorable policy environments for business success in markets around the world.

This interview was conducted by Doug Strub, a Project Manager with the Center for Innovation, Trade, and Strategy at NBR.